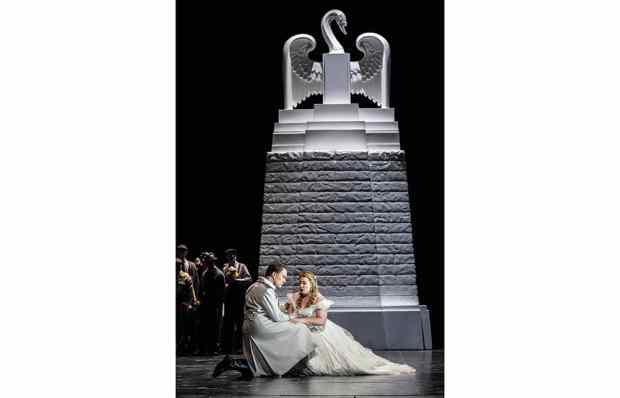

English National Opera has arrived at the Dead City, and who, before Christmas, would have given odds that this new production of Korngold’s Die tote Stadt would ever make it this far? This is late-Romantic music-drama on an exuberant scale; it simply doesn’t lend itself to pubs and car parks (even the reduced version staged – superbly – at Longborough last summer used an orchestra of some 60 players).

Already a subscriber? Log in

Subscribe for just $2 a week

Try a month of The Spectator Australia absolutely free and without commitment. Not only that but – if you choose to continue – you’ll pay just $2 a week for your first year.

- Unlimited access to spectator.com.au and app

- The weekly edition on the Spectator Australia app

- Spectator podcasts and newsletters

- Full access to spectator.co.uk

Or

Unlock this article

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in