The busiest show in Edinburgh must be Grayson Perry: Smash Hits which, a month into its run, still has people queuing at 10 a.m. His original title, National Treasure, was rejected because ‘national’ is a politically loaded term in Scotland. But Perry’s lens is resolutely fixed on England and Englishness. Seen from a Scottish perspective, this riot of rococo folkishness is familiar and exotic.

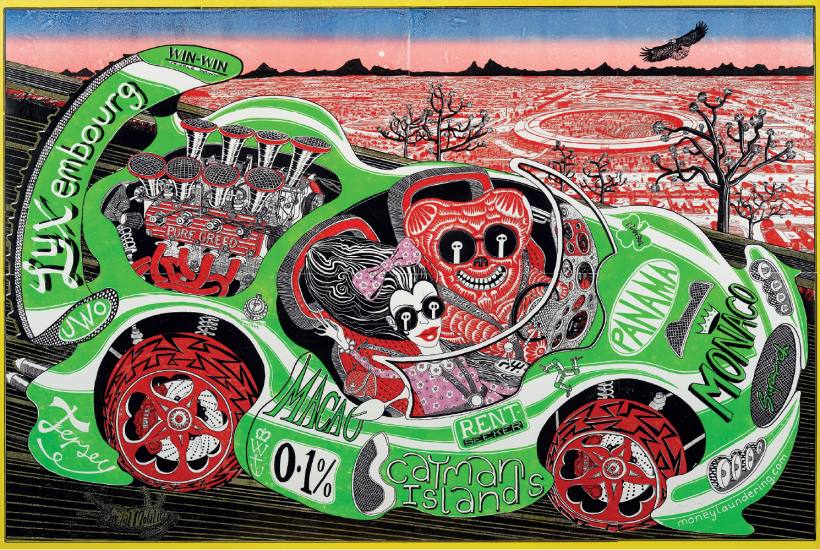

The exuberant exhibition, which is curated by the National Galleries of Scotland but showing at the Royal Scottish Academy and ends on 12 November, slaps the viewer around the face with its huge narrative tapestries, prints and pots. It gallops thematically through four decades, weaving Perry’s own origin tale with the story of England: high and low, rich and poor, ancient and modern. In his beautiful, queasy, messed-up country, Richard Dadd and William Hogarth are reborn to share tales of tax evaders, divine teddy bears and hollow social-media warriors. The colour etching, ‘Our Town’ (2022), maps the ‘emotional geography’ of modern England, sketching a dispiriting fantasy land where drinkers choose between ‘The Selfie and Socialist’ or ‘Style over Substance’ pubs before retreating to their homes in ‘Extremis’, ‘Apathy’, ‘Awks’ or ‘Identaria’. Little England sits beside a blue river called ‘Smug’, in which meaningless modern terms drift by: ‘Mainstream Media’, ‘Gone Viral’, ‘Facepalm’. Presenting the town from the oblique, bird’s-eye angle of an 18th-century map, Perry skewers a 21st-century state of mind with all-seeing grace.

Endlessly inventive and, as he puts it, forever ‘learning on the job’, he is a jack of all trades and a master of them all too, constantly discovering new ways to enrich his ever-expanding vision of England. He’s the greatest artist chronicler of our times, with an omnificent style that’s all substance.

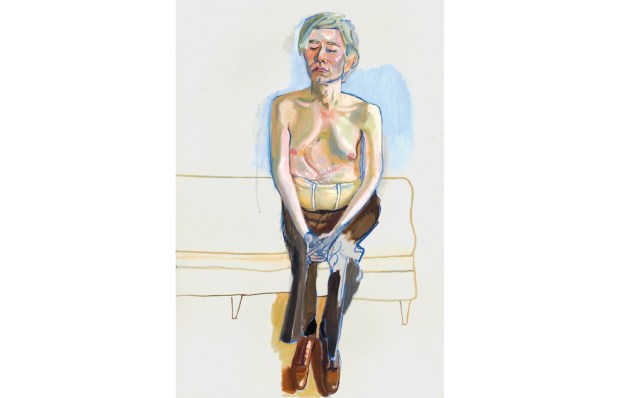

Scotland has no such chronicler. Instead we have Peter Howson, enjoying his own retrospective across three floors of the City Art Centre (until 1 October). Where the relentlessly curious Perry observes, invents, teases and pokes fun at himself and us all, Howson bludgeons with a facsimile of anguish. Famously tortured, he allows his misery to rage off the palette in a parade of interchangeable men, all massive and cross. The meme starts early with ‘The Lowland Hero Spurns the Cynics’ (1985), a Scott’s Porage Oats guy in a huff. Jesus, dosser, Jekyll, Hyde: they’re the same man and the man is Howson. He never wears his distress lightly.

The highlight of the show is the room of war paintings from Bosnia where Howson locates a human touch, expressed in looser, more urgent painting. ‘Zenica’ (1994), a quick study of a man’s face, could be Munch. ‘Frontier’ (1996) has a sunlit symbolist quality, and then you spot the corpse hanging from the tree. These works are stranger, less Howsony. In the post-Bosnia years, he spirals back into himself, pouring out contorted, chiaroscuro oils and, more recently, febrile doodles in ink. A self-portrait stares sourly at the viewer. ‘I was in a black mood,’ explains Howson. No kidding.

Andrew Cranston, exhibiting at Ingleby Gallery until 16 September, paints figments of landscapes, interiors and scatterings of objects that magic up a barely sketched narrative. In contrast to Howson, thundering his chaotic vision across the canvas, Cranston gives us ambiguous, fragmentary hints. Are those jars of frogspawn lined up on the shelf, behind the circle of empty chairs, in ‘Classroom’ (2023)? Why? There are no gallery notes to tell you. Make up your own mind.

In ‘Why Have you Stopped Here?’ (2023), daubs of distemper pixelate the tiles of a fishpond beneath hovering carp and goldfish. It’s a shimmering memory of the fish that once welcomed visitors to the National Museum of Scotland, shot through with the hazy melancholy of a child’s-eye view remembered. ‘Questions of Travel’ (2023) is another museum echo. A boy, seen from behind, is standing in a darkened room, staring at a model ship within an illuminated vitrine. The ship beams like a sacred relic. Cranston leaves space for us to fill in the rest of the story.

‘The Tower’ (2022-3), Jesse Jones’s video, sound and performance piece at the Talbot Rice Gallery until 30 September, is another show that exists in a world before memory and allows us to do the imagining. It’s a disconcerting space, pitch black, apart from two narrow, floor-to-ceiling screens and occasional spotlights, picking out far away objects. A hunched figure in the foreground could be a sculpture or a fellow viewer, impossible to tell for a while. Disorientating choral sounds batter the space from all sides. On the screens, mystical women keen, lament and chant. It’s hard to know what’s going on but the room feels fraught with ritual, threat and accusation. The programme tells us ‘The Tower’ is about ‘the female imaginary’, an exploration of medieval devotional witches. The notes are barely penetrable, unlike Grayson Perry’s refreshingly frank self-written descriptions, but the work doesn’t need to be spelled out. The narrative may be hazy but, like all the best art in Edinburgh this year, the atavistic sensations are very real.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in