On 5 February 1328 the last Capetian king of France was laid to rest in the royal mausoleum of Saint-Denis. It is now 33 years, and more than 3,000 pages since Jonathan Sumption’s first readers followed Charles IV on his last journey, as his funeral procession wound its slow way from Notre-Dame across the Grand Pont and out through the streets of Paris into the open countryside to the north of Europe’s most populous and richest city.

The death of Charles IV led to a crisis of succession that for the next four generations would embroil France and England in a war of unimaginable savagery. At the time of his death his queen was seven months pregnant, and when she gave birth to a daughter in the spring the crown was assumed by the late king’s cousin, the grandson of Philip III, Philip of Valois.

The Valois succession caused little protest at the time – certainly none in the English parliament – and but for two factors would now be happily forgotten. The first of these was that the 16-year-old English King Edward III had inherited a claim through his mother, Isabella; the second was that the land he already held in the south-west of France, the last fragment of an Angevin empire that had once stretched from the Pyrenees to the Scottish march, was as a vassal of the French crown.

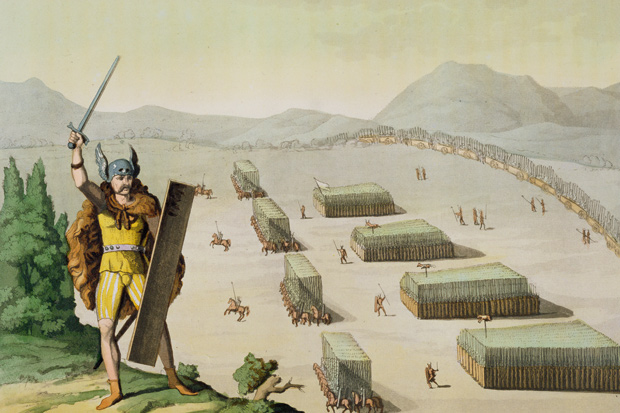

Given the characters of both kings and the expansionist instincts of the French monarchy, it was a recipe for war, and within a decade the series of conflicts, punctuated by uneasy and fragile truces, known as the Hundred Years War had begun. In some ways this was and would remain a civil war, fought out between the great houses of France, but by the time that this final volume of Sumption’s history opens in 1422, it had taken on a more explicitly national character that would have profound consequences for the evolution of both France and England.

For anyone still clinging on to their Shakespeare and the seductive foundation myths of English patriotism, the death of Charles VI at the end of Volume IV might well be as far as they wish to go. The last decades of the 14th century had been as dark as any in English history, but under Henry V the glory days of Edward III and the Black Prince, of Crécy and Poitiers, were back again, with English armies routing the pride of French chivalry.

The early death, in 1422, of Henry V, perhaps the only man who might have made a reality of English claims, was an irreparable loss, but the map of France at the end of the 1420s still shows how much the ‘wheel of fortune’ had turned England’s way. The country was effectively divided along the line of the Loire, with almost all the land to the south of it – contemptuously called ‘the Kingdom of Bourges’ – owing allegiance to the disinherited Dauphin, and the country to the north and the east – Brittany, Normandy, Picardy, the Île-de-France and all the Burgundian lands – acknowledging the young King Henry VI.

Within 30 years all these English conquests would be gone, and how and why this happened is the story of Triumph and Illusion. From the earliest days English strategy had depended on exploiting the dynastic and particularist fissures in French life, but if 80 years of war had taught them anything it was that there was no truce that could not be broken, no act of homage that could not be repudiated, and no French allies – Burgundy, Brittany, Orleans – who would not change sides if and when it suited their interests.

The one thing, however, which England’s hawks had not learned was that with a richer and larger enemy this was a war that could not be won; and the 1430s saw the early stirrings of French nationalism, of which the short and astonishing life of Joan of Arc was both a symptom and a cause. It would be an exaggeration to say that (rather like Alamein) the Dauphin had no victories before Joan and no defeats after, but the defence of Orleans and the subsequent crowning of the Dauphin at Rheims were psychological turning points which put an end to the myth of English invincibility.

The last 500 pages of this volume in fact echo to the ‘melancholy, long withdrawing roar’ of England’s dying empire. The fighting would continue for another 20 years until only Calais remained in English hands, but it went on because it ‘had to’, rather than out of any expectation of victory; because (the same sort of things would be said in 1917)too much English blood had been spilled and too much English prestige invested to give up a French crown to which, from the usurper Henry IV onwards, no English king could have any conceivable claim.

There is really nothing new that can be said about this book that has not been said of the earlier volumes many times over. In the preface to Trial by Battle, Sumption spelled out the principles that informed his approach, and he has stayed true to them ever since. Here, after 43 years of research and writing – or roughly two life spans of a 14th-century French peasant – is the same faith in narrative history, the same willingness to allow events to speak for themselves, the same command and deployment of sources, the same confidence and intellectual stamina that marked the first and every subsequent volume.

The story is told, too, in a style that has hardly changed over the decades. There are few adjectives, with those there are – ‘great’, ‘magnificent’– of a peremptorily conventional stamp. There is the occasional ‘probably’, but that is about as far as Sumption strays into speculation. His sentences are invariably short, say no more and no less than their author intended, and are delivered with the unanswerable finality of a judgment. He perhaps overestimates his readers’ stamina – there are only so many captured bastides, slaughtered garrisons and cancelled journées one can take – but that, I imagine, he would regard as our problem, not his. No man, as Dr Johnson said of Paradise Lost, would wish it longer, but there is no doubting Sumption’s achievement. It is, as everyone says, a ‘monumental’ work.

But what the monument will look like to another generation is an interesting thought. Twenty-plus years ago Allan Massie was already hailing the first volumes as ‘an enterprise on a truly Victorian scale’, and that seems more than ever true today. It is not simply a question of scale either, because it is deeply rooted in a sense of national identity and disinterested scholarship that has more in common with Sumption’s predecessors than with the compulsory angst of so much contemporary history. Whether one likes it or not, other preoccupations, other perspectives and other narratives now hold sway.

When J.M. Roberts wrote his History of the World in 1976, the Hundred Years War still merited a brilliant page-and-a-half of analysis; in Simon Sebag Montefiori’s world history published last year, it gets a single paragraph and a footnote. The events might still resonate in Scotland – the ‘auld enemy’ and France’s toughest ally – as they have done at critical moments of French history, but it is a safe bet that any future history of England will be not be looking to Crécy, Poitiers, Agincourt or Verneuil for its foundation myths.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in