Nigel Townson’s history of modern Spain begins with disaster – or, more specifically, with the Disaster. When an ignominious defeat in the 1898 Spanish-American war lost the country its last major colonies, a crisis of confidence followed, and the ‘Generation of 1898’ set about trying to diagnose Spain’s problem. Since the scope of Townson’s book runs from that year to ‘the present’ (roughly the spring of 2022), there are plenty of crises to cover.

Spain has been unfortunate in its governments. The Penguin History of Modern Spain is a chronicle of ineffectiveness and corruption at the highest levels, and of failures to implement reform. As such, it sometimes reads like a history of missed opportunities. The monarchical Restoration regime proved unable to rise to the challenges of the years after 1898 and was overthrown by General Miguel Primo de Rivera’s coup of 1923, returning the army to its position of ‘political protagonism’.

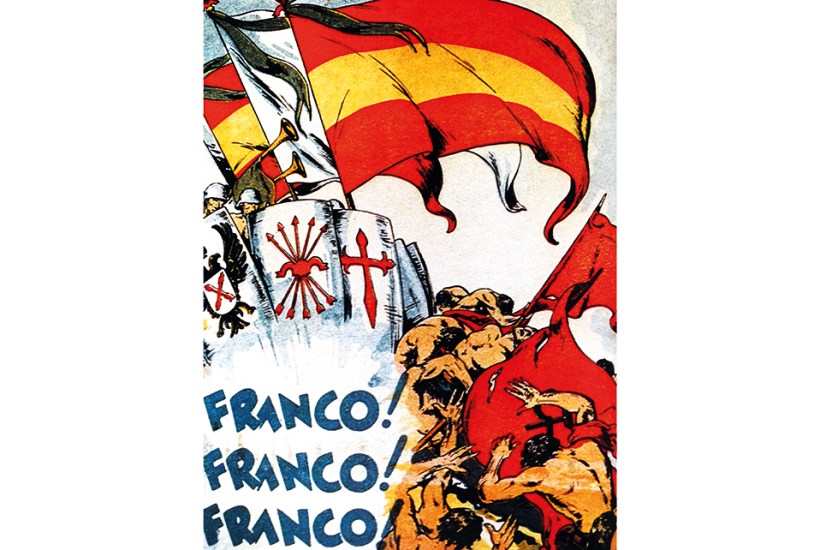

Authoritarianism gave way to the Second Republic and a ‘wave of euphoria’ in 1931 (sending Alfonso XIII into exile), only for those great hopes to degenerate into civil war five years later. Decades of the repressive Franco regime followed the Republic’s defeat in 1939, ending only with the dictator’s death in 1975. Even the triumphant return of democracy has been marked by economic turmoil, political scandal and violence (the rise of ETA is covered in detail).

But as Townson, who teaches at Complutense University of Madrid, is at pains to point out, this hardly sets Spain apart from the rest of Europe. Violence, political chaos, corruption and economic suffering may have been features of the country’s 20th century, but they were not uniquely Spanish. Townson diagnoses a widespread tendency to view the country as an anomaly within Europe. As he puts it: ‘Spaniards’ long-standing sense of failure was the product not only of comparisons with other nations but also of an awareness of the way in which foreigners viewed them.’ He takes foreign historians to task for their obsession with the Spanish Civil War (this reviewer may be implicated as the author of a recent book about people obsessed with it), and aims to provide instead a synthesis of the ground breaking work done by Spanish historians since Francoist censorship came to an end – much of which has yet to be translated into English. These historians are, it seems, less burdened by a conviction of national failure.

If, chapter after chapter, the point begins to feel somewhat laboured, treating Spain ‘in relation to the much broader reality of Europe’ is illuminating. A comparison of the country’s economy with that of other southern European nations reveals ‘the narrative of economic failure’ to be a myth. Setting the arrival of the Second Republic within the context of a Europe in which most of the new republics of the 1920s had already been ‘swept aside by a tsunami of right-wing authoritarianism’ is a useful reminder of just how vast the challenges facing it were both at home and abroad.

Indeed, Townson’s placing of Spain’s history in a wider setting exposes the fact that all too often when we talk about ‘Europe’, what we mean are France, Germany and Great Britain. (At other times, as when comparing the ‘far greater autonomy of the Spanish Church’ under Franco to its counterparts in the communist dictatorships of Eastern Europe, a divergence that is hardly surprising, the comparison feels less relevant.) Townson bludgeons the narrative that ‘Spain is different’ – as the 1960s tourist campaigns put it – so relentlessly that occasionally one feels an urge to whisper, asa mother to a child in a school competition: ‘but you are special!’

The book offers a detailed survey of political, economic and social history, illuminating many of the trends, tensions and power players that have influenced the course of Spain’s modern era. The Catholic Church, Catalan and Basque nationalism, a legacy of clientelism, an endlessly fractured left and frequently embattled middle ground, and the peaks and troughs of working-class activism all receive space. Townson’s attention to economic, political and structural developments means that he sacrifices some of the pleasures of narrative and character: there are too few individual portraits and little scene-setting. This can result in sudden leaps: Primo de Rivera, for instance, who ruled Spain between 1923 and 1930, is gone in a sentence. It’s clear why he was forced to resign, but readers might be interested to know what actually happened.

On the other hand, Townson has made an effort to look for Spanish women – easily disregarded in a patriarchal society – and finds them in observers, protestors and historical actors. He describes, for example, the women in Madrid in 1917 who blocked the city’s tram tracks with telegraph poles (and, where necessary, their own children) during a strike, without, according to a bewildered police agent, ‘letting a single man join their groups’; and the efforts of the nationalist Sección Femenina during the Civil War. He does not assume that the effects of any given phenomenon on Spanish men is the same as their effects on Spanish society, but broadens the picture (if only by sex) on numerous occasions.

Any vestiges of romance lingering over the Spanish Civil War are stripped away. Townson emphasises the Republican government’s failure ‘to uphold law and order or to govern in a democratic manner’ prior to the Nationalist coup (though the generals attacking it could hardly be seen as democracy’s saviours). Franco’s regime did not merely undo the progressive reforms the Republic had accomplished, thus returning the country to the 1920s, but represented ‘a political rupture that was far deeper than that of Primo de Rivera’ in its assault on ‘Spain’s constitutional, parliamentary and electoral traditions’ (not to mention its suppression of civil society itself).

Even so, Townson argues, rather than taking Spain out of step with Europe, this was more a kind of catching up with all the other lost democracies of the late 1930s. By the time the Allied victory in the second world war did make the Francoist repression (and Axis connections) look incompatible with the prevailing mood in western Europe, the Cold War allowed for Franco’s rebranding as a friendly fellow anti-communist, and for a corresponding ‘global integration’ for Spain, crowned by its entry to the UN in 1955.

Even where Spain has been seen as a positive model for the world (as with its swift and relatively peaceful transition to the present democracy), Townson’s conclusion that it ‘fits well into the pattern of European democratisation’ may read a little deflatingly for what most would consider a remarkable achievement – though he is willing to admit that Spain’s transition was ‘sui generis’. In fact, the oversimplified view of an uneven and imperilled process as one of straightforward success, he implies, underplays the victory of Spaniards in preserving a democracy that they had overwhelmingly wanted.

The book’s conclusion is perhaps inevitably sombre, covering the 2008 recession, corruption scandals, 2017’s ‘far-reaching crisis’ in Catalonia, and Covid, not to mention a newly ‘fragmented political landscape’, from which both Podemos and Vox have emerged. That said, there have also been moments when Spaniards have, once again, provided a model of political engagement for outsiders. The ‘15-M’ youth protests of 2011 tapped into a disillusionment and outrage that was widespread internationally; their initiative of occupying sites in major cities was seized upon elsewhere, most famously in the Occupy Wall Street movement.

The ‘new era of hung parliaments and coalition governments’ may be alarming to anyone with an eye on history – Townson points out that Podemos and the PSOE’s coalition government, formed after the November 2019 election, is the first in Spain since the 1930s – but the country’s hard-won democracy is on firmer ground than it has ever been. Townson’s boast for Spain is that it is now a lot ‘like all other European democracies’ – which may not be a dazzling accolade, but is a success surely worth a little conformity.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in