Ask a roomful of concert pianists to pick their graveyard moment in Rachmaninoff’s Piano Concerto No. 3 (1909) and they’ll almost certainly point to five or so pages halfway through the last movement where an ant nest of piano notes infests a sparse orchestral threnody. When an elderly Vladimir Horowitz performed this passage – lank, dyed pageboy hair framing his Bela Lugosi face, hands darting over and under each other like butterflies – he looked more like a weaver at his loom than a virtuoso at his instrument. There are flickers of concentration, but the overall impression is one of extreme insouciance.

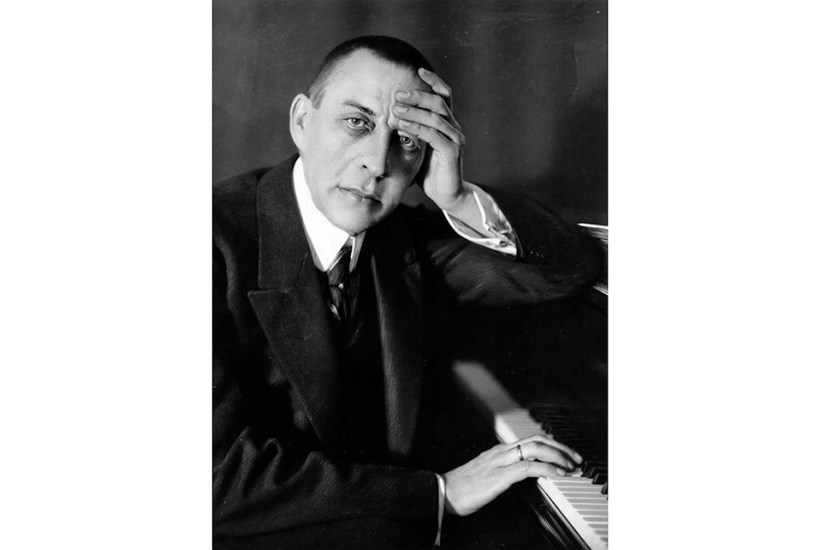

The originator of this style of playing was Sergei Rachmaninoff himself. His recording of this piece, not least in these pages, hints at nothing more than a mild inconvenience soon to pass. Through such performances – and there were many in America in the 1920s and 1930s – this difficult piece became a dowsing rod for the type of pianist who would define music-making in the 20th century, one who might otherwise never have emerged from more traversable Lisztian thickets. It is impossible to understand 20th-century pianism without knowing Rachmaninoff and this concerto, much as a history of pianism in the previous century would be hopelessly incomplete without tackling the dour Anton Rubinstein, a musician Rachmaninoff adored.

These years in exile – precipitated by the abdication in 1917 of Nicholas II, the last emperor of Russia, and lasting until Rachmaninoff’s death, aged 69, in 1943 – are a vital chapter in an already intriguing story of a musician living outside his own time. He is not an altogether co-operative subject, however. ‘I am a Russian composer, and the land of my birth has influenced my temperament and outlook,’ he told a journalist two years before his death. ‘My music is the product of my temperament, and so it is Russian music.’ Could exile really have meant so little to this duck out of water and to the art he produced? Could the unfolding industrial century merely glance off the tough, formal exterior of this polite introvert, leaving not the slightest impression?

In this breezy book, Fiona Maddocks thinks not, though she treats exile as a physical state rather than a psychological condition, never quite living up to the nuances of her subtitle. Bertolt Brecht, who fled Germany in early 1933 when the world tilted so wildly on its axis, was one of many great writers of Exilliteratur, the literary subgenre that shadowed Hitler’s disastrous rule, and in countless plays and films maintained an excoriating relationship with the politics and people of his homeland. Yet he was fuelled not just by the country he had left but also the ones in which he settled. ‘Merely, we fled. We are driven out, banned. Not a home, but an exile, shall the land be that took us in.’ By contrast, the great, reluctant writer Sybille Bedford chose to anglicise herself entirely to hide her shame at her German origins, to the extent of marrying one of Maria Huxley’s many ‘bugger friends’. Rachmaninoff adopted neither pose, living instead in a fug of unbearable, impenetrable sadness.

And then there’s that concerto. Maddocks is right to point to the many recitals and concerto appearances Rachmaninoff undertook in America to rebuild the wealth and property he had left behind amid the Bolshevik chaos. The Washington Post perhaps initiated the waspish tone many critics adopted towards their new resident when it wrote soon after his arrival: ‘Neither is Mr Rachmaninoff professionally a pianist, though he admitted when he arrived in New York that he had been practising of late.’ Maddocks is a longstanding and distinguished music critic, but she talks little about why this work is historically so important, and what those performances meant culturally. (She rightly mentions the American Van Cliburn’s poised and beautiful performance of it in 1958, clinching him first prize in the Tchaikovsky Competition.) Instead, she concentrates on Rachmaninoff’s Moby-Dick attempts to write a fourth concerto, which ends up a distressing coda to the magnificent third.

Maddocks is good on the critical hostility the composer faced in the New World (‘Rachmaninoff comes among us like a very charming and amiable ghost,’ Paul Rosenfeld wrote in 1920, a line and image that would dog him for the remainder of his life), though less good at analysing the sources of this enmity. When she quotes the composer and critic Virgil Thomson’s dismissal of Rachmaninoff’s Piano Concerto No. 2 as ‘mud and sugar’, she would do well to mention here, not later (as she does), Thomson’s studies with the brilliant Nadia Boulanger, the inspirational Parisian teacher who demanded from her students the most urgent engagement with modernism, a fight he fought most valiantly upon his return. Viewed through this lens, Rachmaninoff hadn’t a hope.

Yet this is hardly the only lens through which to appreciate Rachmaninoff’s time in America (1918-30), and his subsequent years in France and Switzerland. There he encountered three overlapping – almost overwhelming – cultural narratives: jazz, immigration and modernism. It is true, as Thomson implied, that Rachmaninoff was not animated by the astonishing modernist works written by his fellow exile Stravinsky, nor those by Scriabin or Szymanowski, let alone Schoenberg or Webern. This is no small insight into his personality and politics, but also into a music scene built largely by his fellow émigrés, shaped by the sounds they had left behind in pursuit of a better life or world. He attended an early performance of Gershwin’s ‘Rhapsody in Blue’ and no doubt would have agreed that the composer ‘had made an honest woman out of jazz’, as people soon started saying. Jazz inflections made their way into his fourth piano concerto, but no further.

So it really was his status as an émigré that is the most interesting aspect of his time in exile, where he rubbed shoulders with White Russian nobles who had lost their titles and sprawling estates and now worked in New York bakeries or waited tables in Russian restaurants populated by punch-drunk émigrés. Yet too often Maddocks occludes this story with lengthy paragraphs on motor cars, on a Baedeker romp through Rachmaninoff’s life pre-exile, and on page-long quotes from small-beer letters or articles. Trinkets and sweetmeats obscure the metaphorical Fifth Avenue palaces.

Still, it is a genial story, well told. ‘Rachmaninoff is here,’ the New York Times announced on his arrival; it was that big a deal. By the time he got there he had already lost two worlds – the country of his birth and the music of his formative years, music left behind in long modernist strides. How nice, however, to read of him attempting to fit in with his adopted land, circling 41 ‘wrong notes’ in a manuscript by the young American composer Henry Cowell since they fell outside the rules of harmony. ‘Do you really think that people now, in composing, should follow the rules of harmony?’ Cowell asked his distinguished confrère. ‘Oh yes,’ Rachmaninoff replied. ‘These are divine rules, the rules of harmony. I too, when I was a boy, sometimes wrote wrong notes.’

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in