I am on the Inspector Morse walking tour in Oxford, which is led by a donnish man called Alastair. We look like the funeral cortege of a man whose death is under investigation.

Oxford is a major character in Morse. I think of it as the antagonist. There is something very cold about the city, and unexpressed. Oxford’s novels are few – elves, talking lions, a bit of class. Its subconscious is rarely exposed: crime fiction must do it.

Three series grew out of Colin Dexter’s 13 novels: Inspector Morse (1987-2000); Lewis (2006-2015), in which Morse is a spectral presence, which suits him (he would be a good ghost); and Endeavour, the prequel (2012-23), which ended last week.

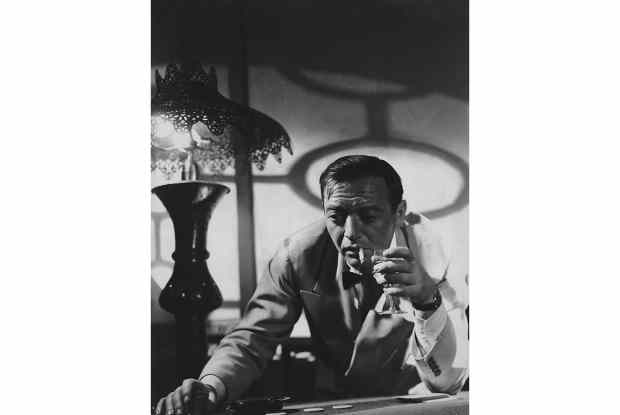

We stand outside the Randolph Hotel.‘It’s not exactly wonderful PR for the Randolph when guests turn up, and they then die in their rooms,’ says Alastair. I’m not sure: the Randolph is devoted to the cult of Morse. When John Thaw, who played Morse, drank in Oxford pubs during shooting, people would say: ‘Here, you’re Morse, aren’t you? Mind if I have a drink with you?’ So he hid in the Randolph Bar. It is now the Morse Bar, filled with photographs of Thaw.

People who have not heard of Morse – though it was seen by one billion people – might wonder who he is. Alastair says when tourists came to the Randolph seeking Morse, the porter would telephone Dexter who would get the bus to meet them. Morse never bought drinks. Neither did Dexter. ‘I was supposed to be in it,’ says a man idly, ‘but I had a very loud laugh, and they wanted a corpse.’

There was mention of a police cadet in the last Endeavour, who may sprout another spin-off, but Colin Dexter’s will is clear: there will be no new Morse until the copyright runs out.

Dexter was a teacher all his life. I think that’s why he liked killing teachers: the series overestimates the murder rate in Oxford by 2,600 per cent. He studied classics at Cambridge and lived in north Oxford. He began the first Morse novel, Last Bus to Woodstock, in north Wales in 1972.

Dexter described Morse as:

A sensitive and sometimes strangely vulnerable man; always a bit of a loner by nature; strongly attracted to beautiful women (often the crooks); dedicated to alcohol; and almost always on the verge of giving up nicotine. In politics, ever on the left, feeling himself congenitally incapable of voting for the Tory party; a “high church atheist” (as I called him), yet with a deep love for the Methodist Hymnal, the King James Bible, the church music of Byrd, Tallis, Purcell, etc., the sight of candles, and the smell of incense. Finally, like me, he would have given his hobbies in Who’s Who as reading the poets, crosswords, and Wagner.

Morse didn’t get into Who’s Who. One of the essential elements of his success is his failure. He never finished his degree, and nothing matters more in Oxford.

Alastair points at St John’s College across St Giles’, and says it was Morse’s college, and A.E. Housman’s college. Housman left after an unhappy love affair, as did Morse. We wander past the Ashmolean Museum to the Radcliffe Infirmary. We pause in Jericho. It was, Alastair says, Jude the Obscure’s Beersheba and the place where Morse went to see Last Tango in Paris, though 101 Dalmatians was playing instead, which made him sulk. ‘I like the fact that Morse is a downbeat character,’ a man tells me. ‘He’s not a person who one would necessarily want to emulate.’

Morse: the name is interesting. Dexter set crosswords for the Oxford Times under the name Codex. People obsess over his Christian name – it was revealed to be Endeavour in Death is Now My Neighbour in 1996 – and ignore the second name. Mors means death in Latin. (It misses the ‘e’ as Morse does. He told people his Christian name was Inspector.) The best scene in the final episode of Endeavour was in a graveyard. Morse was given a pistol by his mentor, Inspector Thursday (Roger Allam), a man he loved. He loaded it with one bullet, the camera hid behind a bush, and we heard a gunshot: Russian roulette.

Tourists stay in the Randolph – so did the actors, and so do I – which has the best rooms in the city. I sit in one, lush overlooking the Martyrs’ Memorial, and speak to DI Mather at Oxford CID. He has Morse’s job. There is a sign in the window of the police station on St Aldate’s that says ‘Inspector Morse’s Office’ and a Morse cardboard cut-out floating around the building, which sometimes appears at CID dinners. He sounds tired.

‘I suppose he is a great detective,’ he says, ‘because he always solves the case. They [the producers] have done me huge favours in terms of detective recruitment for my team in CID. Oxford is still one of the most famous police stations in the country and it remains an iconic place to be a detective because of the Morse series.’ DI Mather agrees that Lewis ‘is more representative’ of a modern policeman than Morse. He adds: ‘I do share Morse’s love of opera, but I am terrible at crosswords.’ As far as he knows, no one has solved a case using a crossword clue.

There is a Morsefest at St Barnabas Church in Jericho. The theme tune is playing on a piano, then a violin. I meet a man who moved to Oxford after watching Endeavour. He saw Shaun Evans, who plays Morse in Endeavour, in Walton Street, thought ‘it was a sign’. I meet a man who has Morse’s numberplate plus one letter and was having a Morse-themed lunch the next day at the Trout Inn in Wolvercote. I meet a woman who has been guiding Morse tours since 2006. ‘Women love him,’ she says. ‘Endeavour has brought some young people. Now I have girls who are “be still my beating heart!” when they talk about Shaun.’

Laurence Fox, who heads the Reclaim party and starred in Lewis, was invited to Morsefest, ‘but he only comes to Oxford for conspiracy theories about traffic management’, says the organiser. We watch Morse scenes on two large televisions and listen to an interview with John Thaw’s daughter Abigail, who plays a journalist on the Oxford Mail: a rather too-friendly journalist. (‘I just want to help.’)

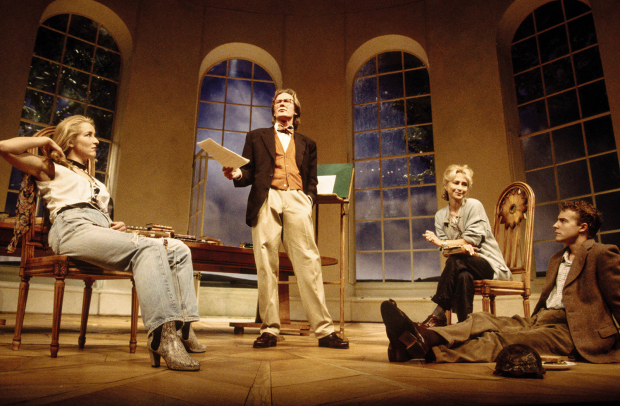

Anton Lesser, who played Superintendent Bright with great delicacy in Endeavour, comes to charm. He was at the RSC for years, and he yearns for the same space in Morse. ‘If I had a fiver for every scene that was cut…’ he sighs. He was excited that Bright had a wife but she didn’t stay long: she was murdered while hanging Christmas decorations. He describes reading the script: ‘Ooh, I get a wife! Ooh, she’s dead!’ Morse solves the case. No one thanks him. Lesser explains the success of Morse: ‘We can vicariously be a cop, a bad guy, a victim – and it’s all safe’.

‘He reminds me of me,’ says the woman I sit next to. ‘He’s grumpy, very independent, and, like him, I know what it’s like to lose a mother and how it affects you. I know what it’s like to be different, and to be in love with a person but not be able to get to them. Not being interested in sports’ – the World Cup of 1966 is agony for him – ‘and all the things other people are interested in and how difficult it can make you feel.’

I think she is right. For all the aesthetics – the blood-coloured Jaguar (a stunt car from The Sweeney so battered it had to be towed); the Headington stone – Morse is about failure and solitude: and this is why he is loved.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.