Halfway up the stairs to the Royal College of Music’s exhibition Music, Migration & Mobility is a map of NW3, covered in red dots. It’s centred on the Finchley Road north of Swiss Cottage, and every dot (there are nearly 50) represents a business or an institution associated, in the middle years of the last century, with a refugee from the Nazis. Herr Zwillenberg offers upholstery repairs; a grocer stocks sauerkraut ‘and all Continental Delicacies’. There are adverts for fundraising concerts and political lectures; a Blue Danube Club and a Café Vienna. It’s urban Mitteleuropa in miniature, uprooted, transplanted, and clinging together for comfort and mutual support. They called it ‘Finchleystrasse’.

It’s mostly vanished now, though there are still many who remember when South Hampstead was a little Vienna or Berlin; and when the members of the Amadeus Quartet – three Viennese refugees and an Englishman – had their Stammtisch at the Cosmo Restaurant on Northways Parade. The scope and significance of the émigrés’ musical contribution to postwar British culture can be encapsulated in the fact that Benjamin Britten’s last string quartet was premièred by the Amadeus Quartet and dedicated to Hans Keller, the Austrian-born BBC producer and musicologist who went on to write sports columns for The Spectator. Keller was married to the artist Milein Cosman, whose vigorous portraits of fellow émigrés are part of the RCM’s permanent collection.

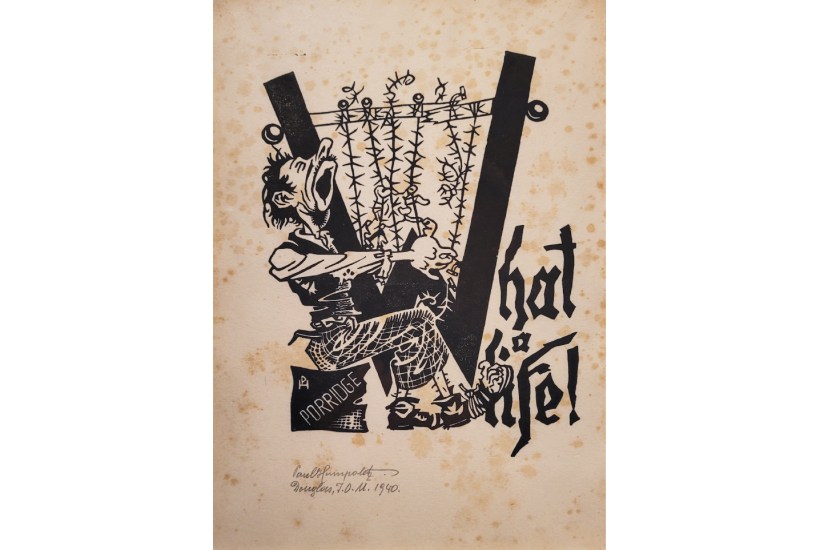

Music, Migration & Mobility explores that legacy. In part, it’s a story of lives remade in the UK: the cello case of Anita Lasker-Wallfisch, who survived Auschwitz and Belsen and founded a dynasty of British musicians, is plastered with cheerful luggage labels; testament to postwar tours as a member of the English Chamber Orchestra. But there are some sharp jolts to British complacency, the bleakest being artefacts from the internment camps for ‘Enemy Aliens’ that were set up on the Isle of Man in 1940. It’s shocking to see those Victorian seaside terraces ringed with barbed wire, and even more shameful to read the recollections of their inmates: committed enemies of Nazism who suddenly found themselves classed with their oppressors and deprived of liberty.

Even here, though, they made music. The founders of the Amadeus Quartet met while interned, and there are handmade posters for a camp revue, with an original score by the Viennese composer Hans Gal. (The internees donated the proceeds to the Lord Mayor of London’s fund for air raid victims.) Postwar assimilation was not always easy: while John Christie of Glyndebourne (built on the talents of the immigrants Rudolf Bing, Carl Ebert and Fritz Busch) lobbied for a free musical labour market, musicians’ unions campaigned against the employment of non-British artists at Covent Garden and elsewhere. Sir Thomas Beecham (who wanted the Covent Garden gig for himself) does not come out of this well.

And yet the names that recur in this exhibition – Franz Reizenstein, Erika Fox, Max Rostal, Joseph Horovitz – will be familiar to anyone interested in postwar British music. Their music, possibly less so. As with any exhibition devoted to the performing arts, physical artefacts are never the whole story. Scores sit mutely in glass cases, with Matyas Seiber’s soundtrack planning sheet for the 1954 animated film of Animal Farm being the exception that really comes to life: pencil-crayon squiggles and zigzags that ping off the page like some abstract artwork.

Vanishingly little music outlives its own time, even music as attractive as Horovitz’s or Gal’s. (Fears that the immigrants would import dangerous new ideas were ill-founded. Gal was a Brahmsian romantic and Keller, posing as the avant-garde composer Piotr Zak, engineered a notorious anti-modernist hoax on the Third Programme.) The centrepiece of the exhibition is a display of original cartoons by the Berlin-born humourist Gerard Hoffnung – rarely seen in public, and something of a coup for the RCM. You can see the careful pencil lines behind the breezy chaos of a hand-drawn poster for one of Hoffnung’s ‘Music Festivals’, held in the late 1950s at the South Bank.

The array of talent that Hoffnung co-opted for his comedy concerts is dazzling: Malcolm Arnold, William Walton and Elizabeth Poston, as well as Reizenstein, Horovitz and Seiber. This was cultural common ground with a vengeance. Finchleystrasse has passed into memory and most of the music – fairly or unfairly – goes unheard, but Hoffnung’s barrel-chested tenors and bowler-hatted tubas are still so familiar that one barely stops to think about their creator. Horovitz, meanwhile, studied with Egon Wellesz and Nadia Boulanger but his best-known work is probably his bouncy 1970 kids’ cantata Captain Noah and His Floating Zoo. What will survive of us is mirth: it’s a curious moral to take from the story told in Music, Migration & Mobility, but one that feels very British.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in