T o describe Pauline Boty as a ‘pioneer’ is a bit like calling someone a ‘one-off’. It’s not an adequate description of her in any way. Pauline was the only female British pop-art painter of the early 1960s. You may not know of her. She died in 1966, aged 28, and her name has remained very much in obscurity ever since.

Pauline, in her youth, appeared to have it all. She had movie-star looks, a provocative intelligence and a magnetic personality. ‘She was beautiful, with this marvellous laugh: clever, very bright, very much the early feminist,’ says designer Celia Birtwell, who lived with her.

Male interviewers would ask: ‘What’s a pretty girl like you doing in a place like this?’

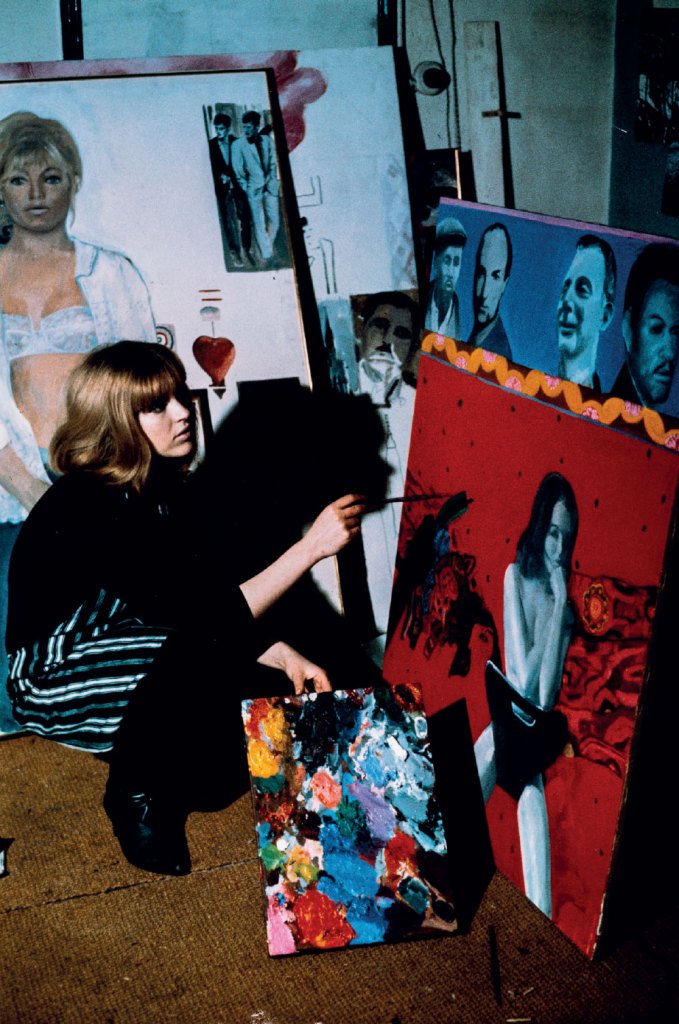

She hung out with acclaimed pop artists such as Peter Blake, Derek Boshier and David Hockney. And her signature paintings of the great cultural figures of the day – Jean-Paul Belmondo, Elvis, an ethereal Marilyn Monroe in a painting she entitled ‘The Only Blonde In The World’ (1963) – are striking and bright. Her collages often featured giant fairground-themed borders, and the work was frequently erotic. She described her art as a ‘nostalgia for now’.

She had interests other than the newly emerging pop culture. She began a movement called the Anti-Uglies, campaigning against especially unsightly post-war architecture in central London. This gained the tall blonde considerable media interest. But her male interviewers would often ask things like: ‘What’s a pretty girl like you doing in a place like this?’

Her accountant father opposed her going to art college. But she won a scholarship to Wimbledon Art School and studied stained glass. It was a start. Still a teenager, she graduated to the Royal College of Art but wasn’t given a place to study painting. The RCA didn’t even have women’s loos at this time.

With the frosty sexism of the art world making progress difficult, Pauline looked elsewhere. She took part in radio debates and appeared as an actress at the Royal Court. She turned up on the silver screen as one of Michael Caine’s conquests, an assistant in a dry-cleaning shop in Alfie.

She was involved with the emerging fashion revolution too, and invited me to the opening of the hip 1960s boutique Palisades. This was a pebble’s throw from Carnaby Street, but a mile away from its military jackets and mini kaftans. Palisades, of which I believe Pauline was a partner, featured items from the very classiest designers, such as Foale and Tuffin and others dedicated to tailor-cut precision.

Artist Pauline Boty had it all – until it all went wrong. Courtesy of Elizabeth Seal-Ward for the Michael Ward Archive, Iconic Images, Gazelli Art House

Artist Pauline Boty had it all – until it all went wrong. Courtesy of Elizabeth Seal-Ward for the Michael Ward Archive, Iconic Images, Gazelli Art House

By 1962, things were looking up. Pauline was featured in Ken Russell’s ‘Pop Goes the Easel’, a famous episode of BBC’s Monitor series, along with three other young British painters: Boshier, Blake and Peter Phillips. Surely this would be a genuine gesture of recognition for the young painters? Huw Wheldon’s preface to the film, however, dismissed pop art as tawdry and second-class.

It probably didn’t help Pauline’s struggle against the art snobs that she would next be seen on television as a dancer on the groundbreaking but brash Ready Steady Go!, the most influential pop show of all.

Throughout this period, despite her lack of fine-art recognition, Pauline was pivotal to the emerging London scene. She greeted Bob Dylan at Heathrow on his first visit to the UK and painted a portrait of Cathy McGowan, the priestess host of Ready Steady Go!.

Her last known painting was of a woman’s posterior, with the word ‘BUM’ spelled out underneath, commissioned for Kenneth Tynan’s revue show Oh! Calcutta!. It was also rumoured that she was the inspiration for the character played by Julie Christie opposite Dirk Bogarde in the John Schlesinger movie Darling, which was scripted by Frederic Raphael.

Out of the blue, she met and married Clive Goodwin, a literary agent, actor and activist, in the space of a fortnight. That’s when I met Pauline. I had just been taken on as presenter of a new show, That’s For Me, produced by Goodwin. We hung out at their flat in Holland Park and they came to stay with me at my seafront apartment in Brighton, sleeping in my Victorian brass bed that had been bought for my neighbour Laurence Olivier (who rejected it because he already had one).

By the mid 1960s, Pauline’s work had become somewhat more political. Her subjects were the Cuban revolution, JFK and Vietnam. Goodwin was editing Black Dwarf magazine, where a coterie of left-wing intellectuals, including the poets Christopher Logue and Adrian Mitchell and writer Tariq Ali, formed around him.

Then it all went wrong. During a pre-natal check up, Pauline was diagnosed with cancer. She refused treatment that might harm the baby. Her daughter, Boty Goodwin, was born in 1966. Pauline died five months later. ‘There is a dark undertow to the life force that drags pure spirits under,’ wrote Tynan on hearing of her death.

Goodwin, meanwhile, collapsed without warning while he was in LA in 1977. The hotel staff thought he was drunk and called the police. He was handcuffed and locked in a police cell and died overnight from a cerebral haemorrhage. The orphaned Boty Goodwin was awarded damages, said to be in the region of $1 million.

She followed her mother into the world of art but the loss of both her parents in such tragic circumstances proved fatal: Boty Goodwin died of a heroin overdose while studying for a masters degree in California, aged just 29. The works of Pauline Boty were stacked away in a barn at her family’s farm in Kent. Gradually, interest in her paintings grew, encouraged largely by the advocacy of her sister-in-law, Bridget.

Exhibitions have been sporadic. But now, for the first time in a decade, her punchy paintings are back in the spotlight. Alongside a new show at Gazelli Art House, there’s a new book out by Marc Kristal and a documentary slated for release next year.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in