An American in Paris was always a stage musical waiting to happen even though it is immemorially associated with Gene Kelly’s extraordinary choreography – and dancing – in a film directed by the greatest of all masters of theatrical cinema, the man who married Judy and sired Liza, Vincente Minnelli. This new stage version sporting the prowess and pyrotechnics of the Australian Ballet is a joy to watch and listen to and it does ample justice to the dance –remember that extraordinary seventeen-minute dreamy ballet sequence? – as well as the lustrous zest and beauty of Gershwin’s score. The original idea for the story and the subsequent script for the film were by Alan Jay Lerner who went on to work with the female lead, Leslie Caron again with Gigi which was also directed by Minnelli. This stage production brings together all the rich interconnectedness between song and dance and things of the heart that give An American in Paris its peculiar soaring qualities as well as its tristfulness. If it’s true as they say that the musical is the one truly original American art form then it’s fascinating in this show to see it linked so resplendently to the glory of modern dance.

We begin with a darkened stage and Gershwin sitting alone at the piano waiting to produce those songs that seem so inevitable they might have been plucked from the air: ‘Embraceable You’, ‘I Got Rhythm’, ‘’S’Wonderful’ and all the rest of them.

And, of course, Gershwin’s music is the archetypal music of the city as in the ‘Concerto in F’ and it’s part of the rich complexity of this show that its Americanness is such an hommage to the city that has always haunted the American mind as the romance of the other place, the supreme delicious bittersweetness of Paris.

The stage show adapts the pictorial quality of the movie – where a given scene might be done via a quotation from Renoir or Toulouse-Lautrec – and does so very inventively by giving it a modernist, even at times a distinctly Cubist slant, and this is an enriching mutation that keeps the show from just being a pantomime of remembered nostalgias.

In a comparable way the complexities and contradictions of the love on display here are beautifully choreographed and dramatised. There’s the heroine’s love for the man who has given his all to her, like a hero, but there’s also the realisation that she’s not in love with him. There is the stupendous crypto-coming together with the GI hero in the staggeringly successful ballet sequence but then, on reflection, in the more muted world of reality there’s the recognition that this is a dream.

What is not phantasmal however is the extraordinary elan of the dancing on show in this extravagant yet thoughtful romp through the different shadings of human possibility in An American in Paris.

The dancing is magnificent. No one will ever rival Gene Kelly but that doesn’t stop Robbie Fairchild from being everything the heart desires as the GI hero Mulligan.

Lise is played and danced with a scintillating skill by Leanne Cope. This is a show that had its Melbourne first-night audience hooting with joy. Part of the charm of An American in Paris – part of the depth of its enchantment – is that like those rare works of art (Hamlet, The Mastersingers) it is actually about the nature of art and it presents the dream of love through dance with such an abundant sense of its precariousness and poignancy. We’re dazzled by the supreme command of the expressive body the dance represents – we crow with delight along with the kids as they sizzle to the high kicking erotic display of the can-can as if it had just been invented. But we never forget the solitary man at the piano and that dark stage, the bareness that is there before the resplendence.

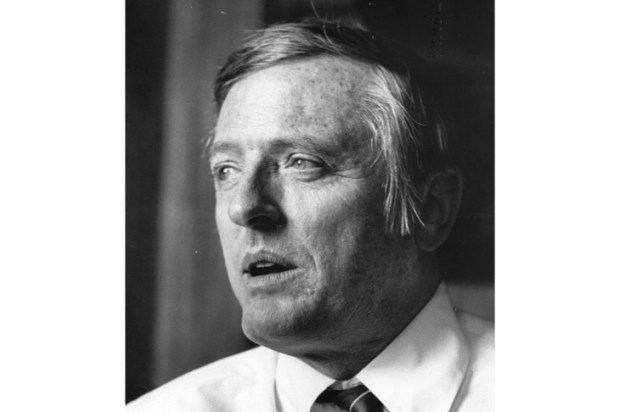

Elsie Rose who died last week belonged to the generation that first experienced An American in Paris and she was someone who might have been a professional singer all of her days if she had been dealt a slightly different hand.

She was the wife of the great Collingwood Football Club coach Bob Rose, a man whose iron integrity was equal to her loveliness, and who encouraged her talent. They suffered the terrible accident which rendered their son Robert a quadriplegic. The account of the effect of this on the Rose family is narrated with great power in The Rose Boys by the poet and literary editor of Australian Book Review, Peter Rose. It is a book that hits the heart of every kind of reader.

Peter Rose has been his mother Elsie’s carer and he has used this as the subject of the podcast he has been doing. If you want the mature voice of adult reflection in the face of family sorrow go to Peter Rose. He has few equals.

He is also, for what it’s worth, an editor who has turned Australian Book Review into an institution which publishes a range of long expert arts reviews as well as administering a series of competitions that put needful money into literary endeavour while also boosting Australian Book Review’s subscriber base in the most sedulous way. Peter Rose is one of the far too rare figures in the literary (or indeed any other artistic) world where anyone will know at a glance that he represents the upper level by any international standards.

At a time when the podcast is regnant you will go a long way to find a more authoritative and articulate voice than his.

Death, as e.e. cummings said, is no parenthesis. Just recently there has been the death of Shane Warne, the reaction to which brings to mind the Sappho poem Catullus translated Ille mi par esse deo videtur (‘He seems to me a god that man’). It was good that Gideon Haigh also wrote of the death of Rod Marsh. There has been the death of Kimberley Kitching which drew elegiac words from the Dalai Lama as well as sorrow from all sides together with vituperation. Elsie Rose’s death closes a chapter of the Rose family saga which Peter Rose has told with grace and gravity.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in