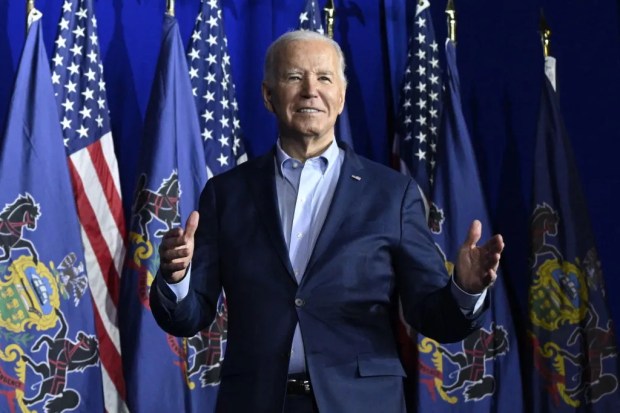

President Joe Biden walked into the grand UN General Assembly chamber this morning with a list of asks, an appeal for greater cooperation among the world’s great powers and a bit of controversy trailing behind him.

Biden’s first UN address came at a difficult time in American diplomacy. The European Union, led by an irate France, is livid over a $60 billion US-Australian nuclear submarine deal that European leaders view as skeevy and duplicitous. And last month’s American troop exit from Afghanistan remains a sore point for contributing nations in the Nato coalition, some of which wanted more time to evacuate their own nationals.

Biden, however, sidestepped all of these disputes. He chose instead to look to the future where he thinks competition between great powers will be a central element of the global landscape, threats like pandemics and corruption will be tackled multilaterally and diplomacy will be the most vital tool of statecraft.

‘We are not seeking a new cold war or a world divided into rigid blocs,’ Biden insisted, no doubt referring to China. ‘The United States is willing to work with any nation…even if we have intense disagreements in other areas.’

Yet in looking to the future, the President was also misrepresenting the present. While Biden deserves enormous credit for sticking by his decision to withdraw all US troops from Afghanistan despite strong institutional pressure, he is simply wrong to insist that America is no longer a nation at war. He is patting himself on the back for something he hasn’t accomplished yet. In the world of foreign policy, it’s vitally important to start with an accurate baseline. And if we are going to be accurate, the truth is that American forces are still very much fighting the war on terrorism, declared 20 years ago this week.

Washington is conducting some form of counterterrorism and train-and-advise operations in as many as 79 countries stretching from Mauritania to Indonesia. Some of those missions include US special operators going out into the field with partner forces. In some instances, like the 2017 presence mission near the Mali-Niger border, these operations have had deadly consequences for US forces.

Notwithstanding the Biden administration’s declaration in July that the US combat mission in Iraq is coming to an end, roughly 2,500 American troops remain in Iraq, stationed across several large bases from Baghdad to Irbil, essentially attending to the same mission they were performing months earlier. This, too, isn’t without risk: drone and rocket attacks from Shia militias, most of which are on the Iraqi government payroll (what irony), target facilities housing US personnel on an almost weekly basis. The deployment in Iraq continues nearly four years after the Iraqi government claimed victory against the Islamic State, a group now relegated to hit-and-run attacks against Iraqi military convoys and kidnapping operations in the dead of night.

Nearly 1,000 US forces are located across the border in neighboring Syria. What those troops are doing is anyone’s guess. The Defense Department insists the deployment is about helping Kurdish forces keep a lid on Isis, which hasn’t governed any territory in Syria in more than two years. But in actuality, the US mission in eastern Syria is dictated by inertia, not necessity. Ask three different experts what role US troops are actually performing in Syria, and you will probably get three different answers: defending the viability of a de facto Kurdish state in the northeast, preventing Syrian dictator Bashar al-Assad from accessing the country’s oil fields, complicating Russia’s and Iran’s consolidation of control in the area.

None of these missions have been debated — let alone authorized — by Congress. Yet the US presence there goes on, virtually unquestioned by the foreign policy establishment.

This discussion would be incomplete without mentioning US drone strikes, a counterterrorism technique first used during the George W. Bush administration, codified during the Obama administration, and expanded by the Trump administration. After taking a few months to review the drone program, the Biden administration resumed strikes in places like Somalia and is increasing surveillance operations in the skies over Niger, Chad and Mali.

That doesn’t sound like a nation turning the page on its post-9/11 wars. In Biden’s assessment, ‘the world of today is not the world of 2001’. True enough. The US, however, is still very much fighting the wars of the past. And we shouldn’t pretend otherwise.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in