In 1772 the 15-year-old Mozart wrote a one-act opera set, like The Magic Flute, in a dream world. Il sogno di Scipione was based on an account in Cicero’s Republic of a dream experienced by the Roman general Scipio Aemilianus while serving in North Africa in 148 BC. In the dream the younger Scipio is visited by his adoptive grandfather Scipio Africanus, who foretells his destruction of Carthage, dishes out advice on dealing with populist politics and shows him ‘the stars such as we have never seen them from this earth’.

Scipio’s is a recurring dream: it inspired Dante’s vision of Heaven and Hell and it returns to haunt us in Colnaghi’s latest exhibition Dreamsongs. But instead of Cicero’s original, this show takes its cue from a 5th-century commentary by Macrobius that divides dreams into five categories — enigmatic, prophetic, oracular, nightmare and apparition. Hopeless. Categorising dreams is like herding witches’ cats — within minutes of entering the gallery I was happily lost (partly thanks to the absence of labels).

Dreamsongs is a high-end car-boot sale of the unconscious in which it is a pleasure to rummage. Spanning five millennia, and cutting between periods, subjects and styles, the show has the authentic feel of a dream sequence in which nothing is sequential. It sensibly avoids the obvious. There’s only a light dusting of surrealists, represented by lesser-known works — Raymond Daussy’s ‘Shadow who found its man’ (1949) is a real find — and the selection of old masters is just as quirky. Cranach’s ‘Melancholia’ (1532) is a marvellous oddity, picturing a depressed young woman with wings confined to a nursery full of bouncing babies. Anyone would succumb to melancholia minding that lot; to pass the time, she whittles a stake to a point. Who knows where it’ll end?

Blake gets a nod with a set of engravings from the Book of Job and Goya with an edition of ‘Los Caprichos’ — originally ‘Los Suenos’ — open at ‘The Sleep of Reason’ page, its flying monsters cleverly echoed in the bat wings of Sarah Bernhardt’s adjacent bronze ‘Self-portrait as a Sphinx’ (1880). The actress was an accomplished artist, as was the author Victor Hugo, a pioneer of mixed media who threw everything at the paper. The seaweed-covered rocks in his haunting drawing ‘The Hermitage, in Jersey’ (1855) glisten with a black granular texture that looks suspiciously like coffee grounds.

When it comes to haunting, you can’t beat the experts. Fairy painter John Anster Fitzgerald contributes two gems: ‘The Nightmare’, an opalescent watercolour of a woman in a laudanum-induced stupor (the clue lies in the bottles on the bedside table) dreaming of a masked ball; and ‘The Fairy and the Sea Serpent’, a woozy oil that reminded me of Max Klinger’s ‘The Glove’. Klinger’s oneiric masterpiece is a grave omission from any show on dreams, but Anne Brigman’s eerie photograph ‘The Bubble’ (1909) helps to compensate.

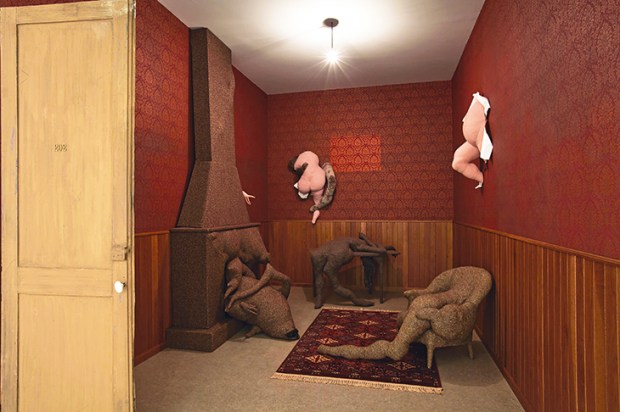

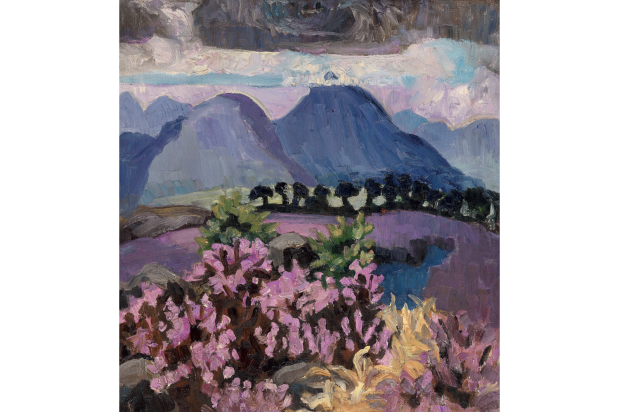

Contemporary art pays homage to Bosch’s ‘Garden of Earthly Delights’ in John Robinson’s uncanny grisaille ‘Ante-Garden 1514’ and Smack’s hi-tech digital ‘Speculum’, but the closest we get to the master himself is in a workshop painting of ‘The Harrowing of Hell’. Its flames are mirrored in Graham Sutherland’s ‘Teeming Pit’ (1941), a wartime record of a Welsh steelworks going hell for leather, though not in the Colnaghi fireplace, temporarily filled by Jillian Mayer’s animation of a Magrittean blue sky with a fading vapour trail reading ‘YOU’LL BE OKAY’.

The most surreal image dates from 1500: a Flemish School ‘Tricephalous Christ’ in the pose of the ‘Salvator Mundi’ with full face and profile views rolled into one. Who needed cubism? This tiny panel’s elegantly handled distortions are rather less disturbing than the digital warping of Mario Klingermann’s ‘Memories of Passersby I-Version Companion’ (2018), in which an AI brain rearranges old master faces according to its own idea of beauty. But the real plastic surgery nightmare here is Jan van Wechelen’s ‘The Legend of the baker of Eeklo’ (1570-80) with its bakery full of customers patiently queuing to have their heads cut off, temporarily replaced with cabbages, redecorated and fired in the oven. If the procedure failed they were cabbage-heads for life.

Decapitation is a suggestive image for a dream state in which our heads appear to float free of our bodies, but the serene marble head by Iranian-born sculptor Reza Aramesh reposing on a plinth is not asleep. ‘Study of the Head as a Cultural Artefact’ (2016) depicts a victim of Isis. We don’t know how the heads of the Bronze Age Anatolian idols known as ‘stargazers’ got separated from their bodies, but with their faces turned to the heavens the most ancient exhibits in this show feel closer to The Dream of Scipio than any others, apart from the most recent: 30-year-old Ugandan artist Godwin Champs Namuyimba’s painting ‘Greatest Desire’, showing an African astronaut with his arms around a globe, dreaming of space.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in