It’s only March, and what a Cohenesque year it has been already.

First, in the wake of the late military general Qasem Soleimani’s surprise appointment with a US-guided military drone near Baghdad Airport, voices warned of an imminent world war. That didn’t quite happen. Nor did Australia entirely fall off the map as a result of the horrendous summer fires.

Now there’s a virus that may or may not plunge the global economy into another Great Depression, sicken or kill untold sufferers and leave our cities at the mercy of zombies prowling the aisles of gutted supermarkets scavenging for rolls of toilet paper.

Also on the paper front, and thanks to the coronavirus shakedown, it looks like I won’t be giving one I was set to deliver in June at an interdisciplinary conference on Leonard Cohen at Ireland’s Maynooth University.

A pity, that. The invitation to present a paper had been a nice little perk for me after having produced a slim work of meditations on my namesake, Book of Cohen, which among other things turns on the question of how one Cohen (that would be me) can be universally unknown while another is universally successful. Possibly, I speculated, the answer has something to do with relative talent. But I also came to see Leonard might have had the better jokes.

My Irish paper was about Cohen’s underappreciated importance as a funnyman, a relatively novel theme in its own right, but also one that could have been just what the doctor ordered amid the current international hysteria.

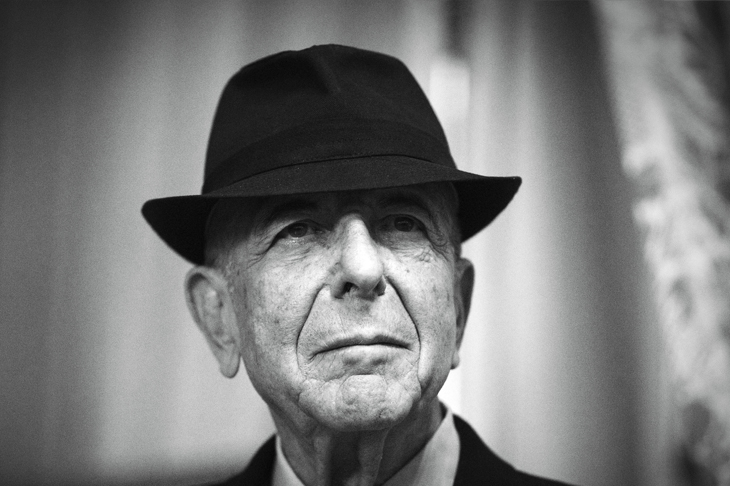

It’s fair to say humour isn’t the first thing that comes to mind when most people think about Leonard Cohen. His creaky voice comes at you as if from the lobby of a biblical plague. Indeed, in his lifetime he was accused so often of trafficking in late-night misery and emotional mayhem as to render it a critical cliché reprised ad infinitum not to mention nauseam.

The charge of depression was often levelled at him as well, with a smile, almost a smirk, and a shake of the head for the drudge in the garret who has spent a career vanishing into imaginative sinkholes. To this Cohen more or less admitted, albeit with a wry grin in one interview, saying yes, he sometimes felt so depressed about the world, so much so that he had even given up thinking about suicide.

In fact, as Cohen understood impressively well, anything can be a laughing matter if you know where to look.

There really is, as somebody once sang, a crack in everything: that’s how the smiles get in.

And those smiles, I think, are pasted over pretty much all of his fifteen studio albums, his two novels, various collections of poetry and hundreds of concert performances (including, perhaps especially including, the one where he appeared on stage on horseback at a festival in Aix-en-Provence, France) up to the final show of his career eight years ago in Auckland, New Zealand.

Even his record titles could be droll: Greatest Hits, for instance, with its devilishly self-deprecating liner notes, first came out when he basically had no hits to speak of.

They’re pasted all over his amusing poetry of rejection, his inimitable knack for mocking his own emotions as he gazes like an awestruck observer at the ridiculous dimensions of his own melancholy pain in the face of those who really prefer handsome men but in his case are only making an exception.

As the chap with the ashtray voice once put it himself, ‘When things get really bad, you just raise your glass and stamp your feet and do a little jig, and that’s all you can do.’

For me, even the Canadian singer’s most supposedly mordant work can be better understood as a particularly striking expression of what was at the time of his emergence in the late 1960s a new style of twentieth-century North American Jewish humour. My session was to have looked at the evolution of a particular Jewish comedic form that began at least as early as the previous decade with the emergence of Lenny Bruce, and continues to some degree to the present day with comedians such as Larry David.

The session was to have examined how Cohen was shaped by, and ultimately contributed to and helped further define, the associated manners and language of this highly ambivalent movement in which traditional Jewish self-deprecation was for the first time blended with a burgeoning cultural self-confidence.

My argument would be that it is the critics rather than Leonard Cohen who are telegraphing perpetual despair — rather than being in on a pretty fabulous joke. ‘You get tired, over the years,’ Cohen once grumbled of this particular lack of appreciation, ‘of hearing that you’re the champion of gloom.’

An example of this — there are so many — would be his well-known 1988 track, Everybody Knows, in which the artist might as well have been writing about Covid-19: ‘And everybody knows that the plague is coming / Everybody knows that it’s moving fast…’ As the lights of the global city flicker and impending chaos hangs in the air like the smell of fresh gunpowder, the artist pauses for a moment to pay a mighty final tribute to his beloved lady:

Everybody knows that you love me, baby

Everybody knows that you really do

Everybody knows that you’ve been faithful

Er, give or take a night or two

Hilarious. ‘Among those whom I like or admire I can find no common denominator,’ W.H. Auden once observed, ‘but among those whom I love, I can; all of them make me laugh.’ This is true and this is strange, because Cohen’s sensibility at moments has always made me laugh, and perhaps never more so than in Cohenesque times such as these.

‘Tears of Sorrow or Tears of Laughter? The Luminous Psychology of Leonard Cohen’s Humour’ may not, alas, get an airing this summer in Ireland, but the subject’s work still deserves the widest possible exposure in 2020. Please raise a glass and stamp your feet and do a little jig. As Dionne Warwick almost once sang, what the world needs now is Lenny, sweet Lenny.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.