‘Bigger,’ said Sir Osbert Lancaster when asked the difference between his work for the page and for the stage. ‘Definitely bigger.’ For almost 40 years Lancaster was the ‘pocket cartoonist’ for the Daily Express. He had remarked to the features editor that no English newspaper had anything to match the little column-width cartoons of the French papers. ‘Go on,’ said the editor, ‘give us some.’ On 1 January 1939, Lancaster gave them the first of around 10,000 line-drawn cartoons. His subjects were the war, the Blitz, the weather, Stalin, Hitler and Dr Spock, the Swinging Sixties, the Common Market, the test tube baby and the topless swimsuit. His heroine, his alter ego, was Maudie, Countess of Littlehampton, a wasp-waisted symbol of sanity in an increasingly insane world. In the front-page cartoon of 19 March 1963, we see Maudie in a box at the ballet. A shirtless Nureyev-a-like is performing a grand jeté. ‘Is that the one,’ she whispers, ‘we swapped for Burgess?’

This season, the Royal Ballet’s Christmas show is Coppélia, danced by the company for the first time since 2006 with Lancaster’s sunny, funny sets and costumes. The stage was Lancaster’s destiny. Aged 11, he was taken to Sergei Diaghilev’s 1919 production of The Sleeping Beauty at the Alhambra. Osbert remembered Lydia Lopokova as the Lilac Fairy and the ‘dazzling’ sets by Leon Bakst. ‘For weeks afterwards, my drawing books were packed with hopeful but pathetic attempts to recapture something of the glory of that matinee, and there and then I formed an ambition that was not destined to be fulfilled for more than 30 years.’

Those 30 years between the Alhambra and his first designs for Sadler’s Wells were not wasted. All the while, he was observing, sketching, taking notes for future sets, props and, especially, costumes. Osbert Lancaster (1908–86) was a prep-school dandy. On Sundays at St John’s in Notting Hill he had loved the catwalk of the nave: the feather boas, veils, gloves and that must-have accessory — the prayer book. He knew his epaulette from his plastron, his aiguillette from his astrakhan. He could tell a cap badge at 40 paces. At Charterhouse, the school of William Makepeace Thackeray, John Leech and Max Beerbohm, he had chaffed against schoolboy ‘sumptuary laws’. The headmaster waved him off as ‘irretrievably gauche’ and ‘a sad disappointment’. Between Charterhouse and Oxford, Lancaster grew a moustache. ‘Half Balkan bandit, half retired Brigadier,’ said one later friend. It was, Lancaster admitted, ‘a compensation for something or other, but don’t ask me what’.

While (not) reading English at Lincoln College, he invented the Osbert look: striped collar, pink shirt, paisley bow-tie, spotted handkerchief, cane, waistcoat monocle, hat with the brim turned up, carnation in buttonhole, umbrella tightly furled, velvet smoking jacket with quilted lapels, oriental dressing gown, tailcoat and Turkish cigarette. (Not necessarily all at once.) Hours that might have been devoted to Wordsworth or Anglo-Saxon (‘insufferable’) were spent dressed highwayman-style as Marat for the dramatic society or at the Ruskin School of Drawing with ‘charcoal-smeared girls in ostentatiously dirty overalls’. He took an ‘honest Fourth’ and failed his Bar exams three times. At the Slade School of Art he studied under Vladimir Polunin, former scene painter for Diaghilev’s Ballets russes. Polunin was both model-maker and matchmaker. He introduced Osbert to Karen Harris, the future Lady Lancaster.

‘It’s all very well drawing funny pictures,’ said Osbert’s Uncle Jack, ‘but it doesn’t get you anywhere.’ Oh, but it did. Assistant editor at the Architectural Review, art critic for Night and Day, front-page cartoonist for Max Beaverbrook’s Daily Express. (‘Old brute,’ said Lancaster. ‘He was a bastard, but by God he knew his journalism.’) Lancaster’s books were bestsellers. Fondly, mercilessly, in Pillar to Post and Homes Sweet Homes, he sent up English taste and architectural fashion. In four-poster beds in Stockbrokers’ Tudor mansions and on hard stools in Functional Flats, his readers, surveying their rooms a little sheepishly, admitted: ‘He’s got me.’

In 1951 Lancaster was invited to design for Pineapple Poll, a comic ballet choreographed by John Cranko to music by Arthur Sullivan. In Lancaster’s sketches we meet pretty Poll disguised as a sailor in matelot trousers and the tightest of Breton stripes. Over ten years Lancaster set the scene for more than 15 operas, plays and ballets. He was particularly keen on Covent Garden where there were ‘always splendid rows going on everywhere’. Stage hands delighted him as much as prima ballerinas. In his 1963 Christmas card, Lancaster drew a cutaway stage. Under the lights: ballerinas en pointe, tutus, roses. In the wings: scene shifters with hairy forearms and bottles of ale on the go.

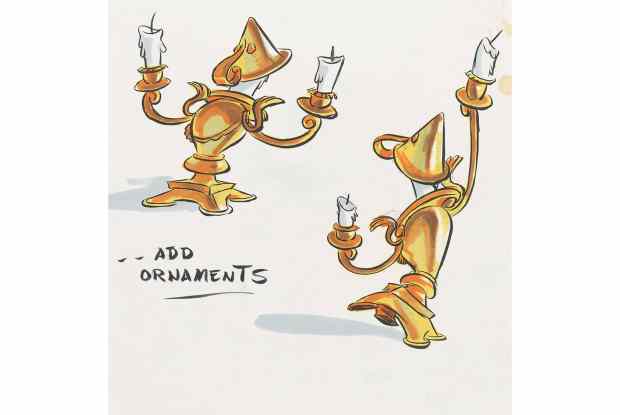

At Covent Garden Lancaster created sets and costumes for Dame Ninette de Valois’s Coppélia (1954) and Frederick Ashton’s La Fille mal gardée (1960). Coppélia, inspired by a story by E.T.A. Hoffman, tells of the village toy-maker Dr Coppelius whose beautiful Coppélia doll sits reading at the window. Franz, a village boy, is enchanted. Swanilda, his fiancée, is enraged. Swanilda steals the key to the workshop, Franz climbs through an upstairs window: hilarity and pirouettes ensue. In the Act One sets, Lancaster, who on student trips to Germany had fallen in love with baroque palaces and pitched cottages, gives us pastiche pastoral: cartouches and scrolls, urns and curlicues, gables galore.

Colin Maxwell, Covent Garden’s production manager, remade the sets for Coppélia’s revival in 2000. Backstage, Maxwell shows me the original scale drawings and Lancaster’s model, a charming shoebox theatre painted in fading gouache. Maxwell, converting imperial to metric measurements, faithfully recreated the Lancaster sets from sunflowers to doorknockers. Lancaster’s eye for exaggeration, trained in caricature, works wonderfully on stage. Even from the gods, you see every baluster and beer flagon. Writing for The Spectator in 1949, Lancaster had observed that the ideal of the stage designer should be ‘whimsy or fantasy… controlled by a sense of style’. When I ask Maxwell if any artist has ever made a model that simply couldn’t be done he replies: ‘The artist draws a magical world — it’s our job to make it real.’

Lancaster’s Coppélia costumes are exquisite, all dirndl daintiness and impossibly picturesque peasants. On stage, in a pause in the half-dress rehearsal (principles in costume, corps in civvies), I have to stop myself reaching out to pinch the frilled sleeves of Yuhui Choe who is dancing Swanilda. You wouldn’t spot it from the front stalls, but the embroidery on Swanilda’s apron and on Franz’s wide, bell sleeves is patterned with tiny, red-stitched birds. Even in an opera house, Lancaster never lost the pocket instinct.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in