Manon: minx or martyr? There are two ways to play Kenneth MacMillan’s courtesan. Is Manon an ingénue, a guileless country girl, pimped by her own brother and corrupted by Monsieur G.M.? Or is she a pleasure hunter, a man-manipulator, a schemer out for all she can get? In the Royal Ballet’s revival of Kenneth MacMillan’s Manon, Sarah Lamb is somewhere in the unsatisfactory middle. Primrose innocence in the first act, half-hearted harlot in the second, shorn urchin in the third.

Ryoichi Hirano, as Manon’s brother Lescaut, knows what he’s about. Hirano has a nice line in matadors and caped scoundrels. Every duplicitous turn, every dismissive flick of the wrist, speaks of mercenary betrayal. His Lescaut is superbly disturbing.

Vadim Muntagirov, clutching a slim volume, is a sweet, wide-eyed Des Grieux. His gawkiness serves him well as the young scholar dazzled by Manon. We share his surprise and rapture as he discovers that there is, after all, more to life than his quill. Lamb and Muntagirov dance their first pas de deux with a sense of wind in their sails. They almost carry you with them. Lamb’s come-hither bourrées in the bedroom scene are dazzlingly pretty.

The scene at Monsieur G.M.’s party is less convincing. Lamb’s Manon is neither reluctant nor revelling in her success. Hirano, hitherto strong, loses the plot in Lescaut’s drunk dance. Too broad, too loose, too Dame Edna. The tipsy duet between Lescaut and his Mistress (Itziar Mendizabal in a Little Orphan Annie wig) was clowning where it should be tender. Shouldn’t she indulge him, roll her eyes, know he’ll regret it in the morning? ‘He’s drunk but he’s my drunk’, rather than: ‘He’s drunk, but I’m drunker.’

Muntagirov, meanwhile, dances the jilted Des Grieux like a devastated flamingo. Every lift, every line is perfectly gorgeous, hysterically silly. Muntagirov is divine, but he isn’t subtle. On opening night, the lover’s chemistry was off-key. Manon can be magnificent, this one was merely meh.

It is the centenary of the birth of the American choreographer Merce Cunningham, and following a grand hurrah at the Barbican in April the Royal Ballet has joined the tributes. Around the time of Cunningham’s 80th birthday, his younger brother asked him: ‘When are you going to make something the public likes?’ Hardly fair. A few weeks before, Cunningham’s BIPED had received a rapturous standing ovation. He was friends with abstract artists — Willem de Kooning, Ad Reinhardt — but rejected the idea that he was abstract or intellectual. ‘I am no more philosophical than my legs,’ he said. What motivated Cunningham was ‘intoxicating movement’.

The Royal Ballet’s triple bill offers one Cunningham (Cross Currents, 1964), one ode to Cunningham (Frederick Ashton’s Monotones II, 1965) and one contemporary response (Pam Tanowitz’s Everyone Keeps Me). Cross Currents is an exposing piece. Three dancers, black tights, white vests, barest music, minimal, but arduous, movement. Hop, stop, turn, bend. Matthew Ball, Francesca Hayward (exquisite, even dancing flat-footed) and Mayara Magri are endearingly awkward, like students presenting the end-of-term show at a summer maths camp. Their bodies quaver like theremins. This is Large Hadron Collider choreography: charming, but odd.

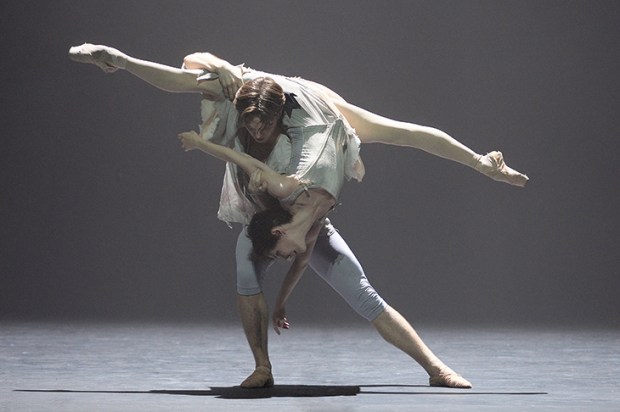

In Monotones II, Melissa Hamilton, Reece Clarke and Nicol Edmonds in white bodysuits, jewelled collars and crystal berets, dance in a state of suspended animation. Ashton marries steel-ruler tension with sighing softness. One gives way, swooningly, to the other.

Pam Tanowitz’s Everyone Keeps Me is a triumph. Gentle and aggressive, courting and warring. Merce Cunningham used chance — throwing dice or tossing coins — to create new, unmeditated sequences. Here, Tanowitz’s nine dancers (four male in blue waistcoats, five female in sherbet dresses) scatter like pick-up sticks. The disposition of many dancers across the small Linbury stage is finely and imaginatively judged. In the final passage, the company link arms across backs: golden youths in glorious union.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in