In the nineteen-thirties, my parents, middle class, mixed-race Burghers from then-Ceylon, now Sri Lanka, honeymooned in Kashmir.

It was a wildly impractical undertaking for a very junior engineer and a music teacher from Colombo, given war seemed inevitable and coming ever closer to the sub-continent.

But Kashmir and its fabled Vale seemed a world away from dusty, mercantile Colombo and they seized opportunities and travelled north up the sub-continent, their travel assisted by friendly Anglo-Indian train drivers who told them of the best, cheapest hotels catering to non-Europeans and where, in Hindu India, they could eat meat, preferably goat, not buffalo.

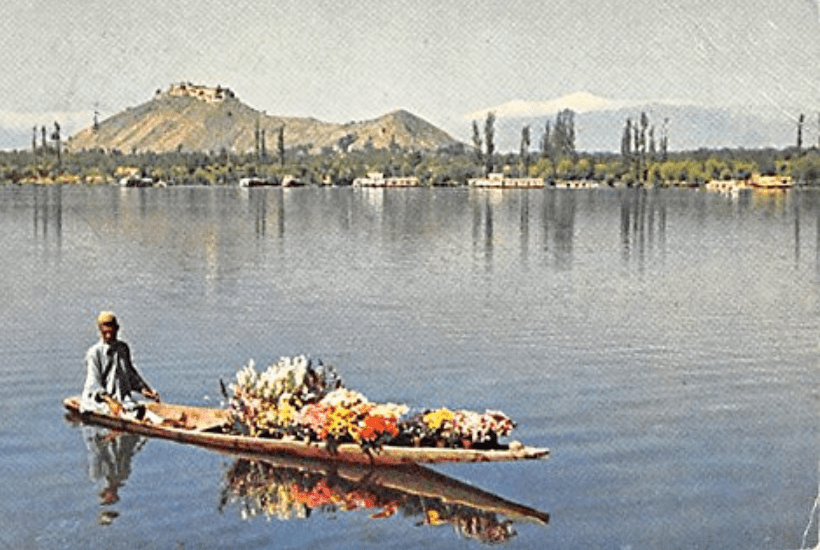

The week they spent in Kashmir, having finally arrived, was to be one of my mother’s happiest memories, treasured, like the tiny sepia photograph taken of the young couple in Gulmarg, the ‘flower meadow’, the towering grandeur of the Himalayas behind them.

My mother wore a flower-sprinkled cotton dress and a borrowed cardigan.

She had fallen in love with a kingfisher-blue Kashmiri shawl in the chowk (bazaar) but it had been beyond her new husband’s meagre resources. She saw it later around the shoulders of an English memsahib strolling in the town.

Kashmiri shawls, since the days of East India Company, were famous for their warmth and light weight, the best shawls, it was said, could be drawn through a wedding ring, so fine was their weave.

The British adored Kashmir for its romantic, Arabian Nights ambience. Prevented from buying land in Kashmir, they rented houseboats that were serviced like well-run hotels, meals and the staff to serve them arriving by and departing by water.

The British were not the first invaders to appreciate the attractions of Jammu-Kashmir.

The Mongol armies of Genghis Khan, storming through the high passes, paused in Kashmir, enchanted by its gentle climate, crystal lakes, flower meadows and beautiful girls with the profiles of Greek goddesses. Genghis founded the Mughal dynasties that ruled northern India for generations, with Delhi their capital, having first sacked and massacred its Hindu citizens.

But it was in the days of the Raj that seeds of the present conflict were sown. The British were never averse to inserting their influence by inserting here a malleable princeling, demoting often by force, a recalcitrant raja there.

We can’t put the entire blame on the Raj. In the grim aftermath of the war years when Indian nationalists of all castes and communities fought for Indian independence, the British, having just – barely – fought off the Axis powers, were faced with Hindu politicians demanding a Hindu government, Muslims demanding a Muslim state, Sikhs demanding ‘Kalistan’ – a Sikh state – and some 73 ‘princely States’ who wanted the British to continue as before.

The result was Partition, the Muslim state Jinnah demanded, a hastily stitched-together plan to at least make the inevitable easier. (It didn’t, of course, Partition caused massacres of thousands of innocent people as families on both sides of the designated borders tried desperately to find security amongst their co-religionists. )

In Kashmir, a Hindu ruled a mainly-Muslim majority province while a Muslim ruled in Hindu Hyderabad. After Independence and the creation of Pakistan, Jammu-Kashmir became a flashpoint, culminating with Prime Minister Modi revoking Kashmir’s semi-autonomous state and declaring it to be part of India. Kashmir, remote, lucky in its geography, remained relatively untouched by the sectarian violence.

India has always kept careful eyes on Kashmir-Jammu, not simply for its strategic importance and its hosting of militants slipping across the border from Pakistan but for another less-well-known reason. Kashmir was the traditional home of one of India’s great political dynasties, the Kashmiri Brahmin Nehrus.

Watching the pictures of armed soldiers, the barbed wire and deserted streets in Kashmir today, I’m glad my parents saw it in happier times. I wish my mother could have afforded that shawl.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in