Struggling to understand the ways of the French, the francophile Winston Churchill reflected whimsically in 1942:

‘The Almighty in His infinite wisdom did not see fit to create Frenchmen in the image of Englishmen.’

And yet today, the Almighty would struggle to create two more similar states in international terms than Britain and France. Similar geographies on the northwest European continent, similar populations (66 and 67 million), economies (5th and 6th by GDP), colonial histories, 3rd and 4th nuclear powers, two of the five permanent members of the UN Security Council, leading members of Nato and, until 2019 (probably), equally prominent members of the European Union. The similarities continue to trip off the tongue: the Commonwealth and Francophonie; trade patterns characterised largely by trade surpluses outside the European Union; historical communications and undersea cable networks dating from empire that still dominate international traffic; and a military-industrial partnership second to none.

Churchill summoned the aid of the Almighty to understand the French, but the German journalist Friedrich Sieburg went further, wondering in his 1929 book ‘Is God a Frenchman?’ Whereas his contemporary, the English writer R.F. Delderfield, penned his ‘God is an Englishman’ series. Is it fanciful to believe that two countries so often divided in history could one day be united in a sort of dual monarcho-republican regime analogous to, but more successful than, Austria-Hungary?

As Britain prepares to leave the EU, today marks the 115th anniversary of the Entente Cordiale when Britain and France came together to eliminate the international friction that, from colonies to fishing rights, had long made co-existence difficult. Ten years later as war broke out, that entente became an alliance to defeat the Triple Alliance powers. World War One saw France and Britain’s economies integrated for four years, arguably closer than at any time until the 1993 Single European Market of the European Union.

One of the architects on the French side of that Franco-British dual economy was the young Jean Monnet, who repeated the trick from 1939-40 and who, three decades later, took it further as a founding father of European integration. On 16 June 1940, Churchill presented to the French government the offer of a Franco-British ‘indissoluble union’ that would see the two empires ‘no longer be two nations, but one Franco-British Union’, with joint citizenship. Following Colonel Nasser’s nationalisation of the Suez canal, in September 1956 the French premier Guy Mollet returned the compliment, requesting of the British government that the two empires be joined as one under the sovereignty of Queen Elizabeth II with ‘a common citizenship arrangement on the Irish basis’. Prime minister Anthony Eden recommended ‘immediate consideration’, but finally rejected the proposal. The French, chastened for the last time by English reluctance to dignify the long-running courtship, turned for solace to Europe and the Common Market and – until the Maastricht Treaty – largely benefitted from the experience. A lonely and unself-confident Britain followed her 16 years later, but did not enjoy the experience.

But what if Britain leaves the European Union and makes a success of it? What if the EU, as seems not unlikely, plunges further into political and economic crisis? What if France, that other state with a heightened tradition of national sovereignty, also comes to realise that the European community years should merely be a parenthesis? In the 1992 French referendum on the Maastricht treaty that divided political parties, the ‘No’ campaign, led by Gaullist Philippe Séguin, argued vigorously against a Europe that ‘buries the concept of national sovereignty and the great principles born of the Revolution’. Though narrowly defeated 51 to 49 per cent, French anti-EU sentiment was not extinguished. Thirteen years later, in the equally high-turnout 2005 referendum on the proposed European Constitution, the ‘No’ vote won convincingly with 55 per cent as a consequence of the widespread fear in France over forsaking national sovereignty for that of a federal Europe. More recently, in the 2017 presidential elections, some 50 per cent of French voters cast a ballot for candidates either explicitly or implicitly in favour of French withdrawal from the European Union; and opinion polling regularly records the existence of a substantial group of French Eurosceptics, not least among elements of the yellow vest movement that has taken off under president Macron.

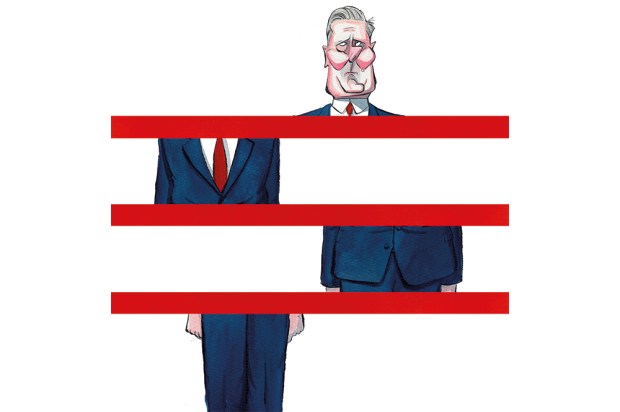

What then if Brexit led to Frexit? And what if the two exits led to a Franco-British Union with a combined GDP ranked 3rd in the world, military power arguably second – and a formidable rugby team. It might solve the Almighty’s nationality dilemma.

Professor John Keiger is a former research director in the Department of Politics and International Studies at the University of Cambridge

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in