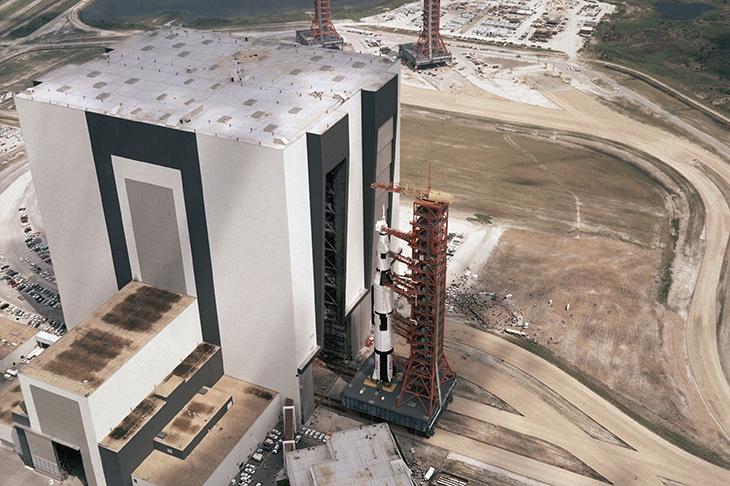

Take yourself back to (or try to imagine) Christmas 1968; a year full of disturbances, dashed hopes and extreme violence at home and abroad. On 21 December, a huge explosion occurred; not, for once, a herald of catastrophe but at Cape Kennedy, where the engines of the Saturn V rocket, ‘the most powerful machine ever made’, were ignited, launching the Apollo 8 mission. Three astronauts in a tiny metal box were thrown up into space. Three days later, on Christmas Eve, they would broadcast back to the world images that would change for ever the way we see our planet.

As they orbited the moon, the first astronauts to do so, they saw the Earth gradually appearing above the surface of the grey, colourless, ‘distressed’ lunar landscape; a blinding light, ‘the only thing in space that had any colour to it’. Technology, at the service of dreams and ambitions, was used to alter understanding and then beamed across the world. Between the Ears on Radio 3 (22 December) reminded us of the utopian fervour of those Apollo missions, that belief in the possibility of progress, not just in technological accomplishment but also in international cooperation.

Before the launch, the American astronauts discussed what they should say when they emerged from the dark side of the moon (for 47 minutes in the lunar orbit they were out of radio contact with the earth). They were promised that their voices would be heard by ‘the largest audience any human had ever had’. What would be appropriate? All three were religious and decided to ‘go back to the beginning’ — those first words in the first book of Genesis. Not until they were circling in space and looking back to Earth did they realise how apt those words would be, seeing our mysterious planet just hanging there in the infinity of space ‘like a jewel’.

The programme also spoke to Nicole Stott, an astronaut on one of the internationally organised space shuttles that followed Apollo. How could she explain to her seven-year-old son what it’s like to leave Earth and look back on it from a distance: ‘I just remember seeing this planet that glowed…’ But she was not just seeing: ‘I was feeling it.’

This was not billed as ‘slow radio’ —programmes that take time to disclose, to reveal, that persuade us to listen at a deeper level instead of rushing along, hearing only surface chatter — but it had the same kind of impact. The crackling sound of the transmissions from space, the disembodied voices, so far away not just in time and space but also in what they were experiencing, took me straight back to those decades when we all seemed to be reaching out to the future rather than drawing in, retreating.

The Creation of an Icon on Radio 4 (produced by Phil Pegum) in the week before Christmas also carried within it far more meaning than simply what was said. In five short programmes, or rather meditations, Aidan Hart took us through the stages of working on an icon of the Annunciation. You need a steady hand when making an icon, an open mind, and a willingness to accept imperfection, especially when working with gold leaf. You need to be present, in the moment, but without trying too hard as this will introduce tension.

There should, explained Hart, be something crude about an icon, almost shocking, because it’s intended to wake us up, to make us think ‘surely they can paint better than that’. The objective is not to portray reality but to provide a window, an access, a way of seeing and believing. The perspective is skewed because we should be able to look at it and also see God behind the icon contemplating us — almost like those astronauts looking down on Earth from

the cosmos.

Strangely, perhaps, we in the West are witnessing a renewal of interest in making icons, with courses introduced at the Prince’s School of Traditional Arts (alongside medieval tiles and Indian elephants) and icons introduced into many Anglican churches. They could, argues Hart, be described as modernist abstract art, a way of expressing realities that are not visible.

On the World Service, Christmas Day was celebrated with a programme from its World Hacks series, which looks at local solutions to global problems, trying to fix small things in the hope that this will make a bigger difference. In this edition, Susila Silva took us from Khartoum to Brighton, seeking out little free libraries, boxes of books that are set up for anyone to borrow from. ‘Take one and leave one’ is the motto of the non-profit scheme.

It was started by Todd Bol who in 2009 wanted to do something in memory of his mother, a schoolteacher. He came up with the idea of building a box, filling it with books, and putting it out in his front yard in Hudson, Wisconsin, for everyone to share, but also as a meeting point for his neighbours. Now there are 75,000 little free libraries in 88 countries across the world. There’s even one in Siberia, where the union of reindeer herders wants to build a network of such book-sharing boxes across the Arctic Circle, a point of connection, free access to stories, poetry, real news.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in