When dining in France, it is considered rude to finish the bread before the main course has been served, and ruder still to slice the bread with a knife, lest the crumbs land in a lady’s décolletage. In China, you should never place your chopsticks upright in a bowl of rice, and in Bangladesh you may eat with your fingers, but should avoid getting sauce above the knuckles.

If you are guilty of any of the above, may I direct you, politely, to a new documentary on the World Service. The programme takes aim at many outdated traditions (including those that resign women to the kitchen), but the conversation is far more informative than censorious and more eye-opening than dour. It makes for particularly delicious listening for the English, for we have long prided ourselves on our good manners, not least in relation to the French.

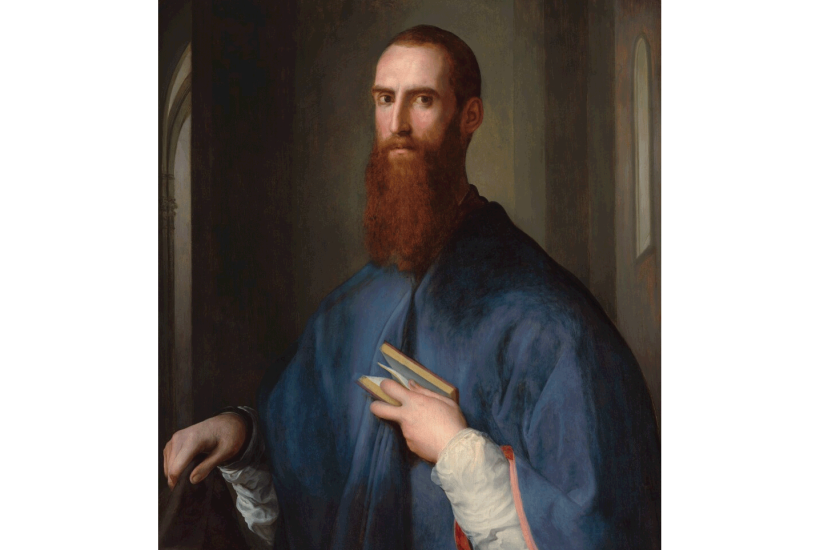

Our Gallic neighbours, it seems, have laid claim to the invention of etiquette on rather dubious grounds. The French étiquette means ‘a label’ or ‘a placard’. It supposedly developed as a reference to the signs one of Louis XIV’s gardeners put up around Versailles to ward people off the lawns. But according to one of the experts interviewed for the documentary that’s a myth; the term is more likely to have developed in the context of courteous behaviour at the Spanish court back in the 16th century. While Henri III of France borrowed the word back – his mother Catherine de’Medici introduced many new rules that had been learned across Europe – etiquette was by then most popularly associated with the Italians.

This was due in large part to the publication of Il Galateo in Venice in 1558. Penned by a Florentine, Giovanni della Casa, the highly readable treatise offered the kind of advice that was most valuable to inhabitants of plaguey, overcrowded cities. Readers were discouraged from sniffing plates of food or cups of wine, even their own, because people were worried about dripping noses. Public nose-blowers (there was a lot about noses) were cautioned not to inspect the contents of their handkerchiefs. Rubies and pearls, noted the wry della Casa, were seldom to be found tumbling from the human brain. The author issued many more stout warnings against irritating behaviour, including offensive teeth-grinding, heavy breathing, metal-scraping, whistling and unmelodious singing. I would love to have heard even more about his book. It is surely ripe for a reprint.

Books – at least some books – have the potential to connect us to God as well as to each other. This was brought home to me last week as I listened to a preview of the Good Friday Meditation on Radio 4. The Rt Revd Dr Helen-Ann Hartley, Bishop of Newcastle, has chosen the Sycamore Gap as the starting point for this sermon. Until it was senselessly chopped down by vandals last September, the tree had stood as a beacon of strength in a windswept dip of Northumberland. For many, it also had a religious dimension.

Trees, as we are reminded, serve to break the horizontal realm we inhabit and show that Heaven and Earth are joined. The Sycamore tree’s particular position in such a wide, open space lent it a particular poetry. As part of her meditation on the sorrow that attended its felling and the sorrow inherent to Good Friday, Hartley muses on ‘The Dream of the Rood’. The poem, which dates to roughly the 8th century, concerns the felling of the tree used for the cross upon which Christ was crucified.

The brief discussion of the poem was led by Michelle Brown, an academic and Lay Canon, who also addressed the World Tree, familiar from Anglo-Saxon and Celtic myth, and the Tree of Life. This part of the meditation powerfully evoked for me not only the longevity of myths, but the life cycle of trees, culminating in the paper those myths were written upon. The message that trees go on nurturing and enriching life and witnessing rebirth is beautifully borne out in the programme, with clips from news bulletins announcing that the Northumberland Sycamore is not, as formerly feared, extinct. Shoots have developed from parts of the tree salvaged soon after the disaster. The stump itself may still grow.

‘Out of sight is the life being drawn up through the roots that are still there,’ observes one participant to the programme. ‘Today Jesus lies buried,’ adds Hartley, ‘but life is stirring again.’ From pain grows hope. There could be no greater meditation for this time of year.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in