There is the feeling that after ten years of political failures and assorted cultural nonsense the community is yearning for simpler times with answerable questions. This might explain why a number of books – many of them pretty good – on historical themes appeared in 2018.

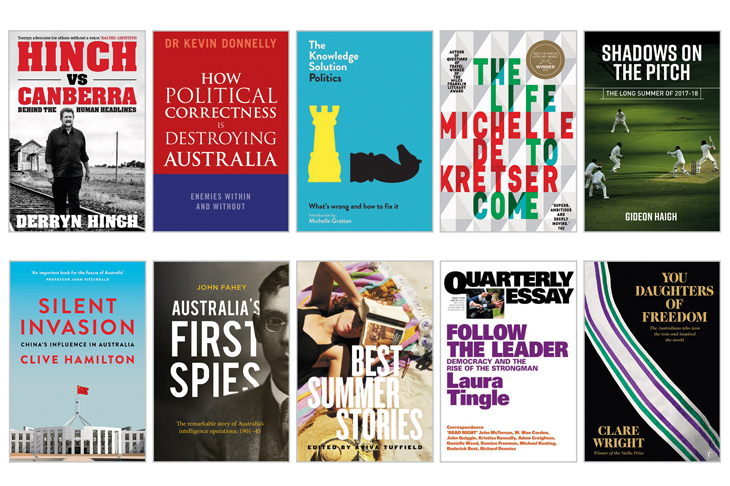

One of the most interesting was Australia’s First Spies by John Fahey (Allen & Unwin). He burrowed through the archives to find intriguing tales of agents and operatives, going back to the Federation era. Fahey takes the view that covert activities demonstrate the real thinking of political leaders, and if that is true then the early leaders of Australia were an independently-minded lot. In fact, the first real intelligence operation was against the British, trying to manipulate them into opposing French expansion in the South Pacific. There was a series of other operations, often run on an informal but nevertheless effective basis, over the next few decades, and all of it makes remarkable reading.

Another book to re-invigorate a near-forgotten chapter of history is Claire Wright’s You Daughters of Freedom: The Australians Who Won the Vote and Inspired the World (Text Publishing). The story is loosely wrapped around a famous banner painted by Dora Meeson Coates, carried in some of the major suffragette marches (it is now on display in Parliament House after being lost for many years). By the time the parliament voted in 1902 to extend the franchise to women the campaigners had won broad support for the idea (especially because the New Zealanders had already done it, and the vote had been given to women in South Australia without the sky falling in). The road was much harder in Britain, where many of the Australian women became involved with the bruising battle. Wright believes that the Australian experience was a crucial element in winning the right to vote in Britain and elsewhere, and it is hard to disagree.

A different take on social history is A Coveted Possession: The Rise and Fall of the Piano in Australia by Michael Atherton (La Trobe University Press). The first piano arrived in 1788 and for a century after that having one in the house indicated class and respectability. Pianos were also the focus of family gatherings and community sing-alongs, providing a sense of social cohesion. Recorded music saw the beginning of the piano’s decline but this fascinating book concludes with a look at the new generation of piano-makers, perhaps heralding a renaissance.

A much less happy story is One Last Spin: The Power and Peril of the Pokies by Drew Rooke (Scribe). Rooke traces how we arrived at the point of having nearly 200,000 poker machines in pubs, clubs and casinos, buttressing his research with interviews with opponents, advocates, addicts, manufacturers and politicians. He concludes pokies are a mug’s game, expressly designed to extract money from the people least able to afford it. Scary stuff, but no solution is in sight.

Shadows on the Pitch (Wilkinson) is a compilation of the columns of cricket journalist Gideon Haigh, who is now attaining the status of national institution. Covering the last season, he looks at the critical games here and overseas, bringing his vast experience and trademark wit to bear, whether he is talking about the play or the players. The nadir of the season was the ball-tampering scandal, and Haigh devotes several columns to analysing it. He concludes that it was due, at least in part, to the win-at-all-costs culture of the Australian team (and the administrators and money-men behind the players) and the intense competition between the different forms of the game. He believes that Australian cricket will recover from the disaster but it will take a while and will require some deep reflection.

The winner of the 2018 Stella Prize was Alexis Wright’s Tracker (Giramondo), about Aboriginal leader, activist and entrepreneur Tracker Tilmouth. Wright collected a huge number of anecdotes and opinions on the man, fitting the oral tradition of indigenous story-telling. Sometimes this works well but in other places in becomes a muddle of conflicting opinions, and one wishes there was an authorial voice to provide clarity. Nevertheless, the no-nonsense views of Tilmouth come through, especially his views on taking personal responsibility and his rejection of the museum mentality. At 640 pages the book is not an easy read but Wright deserves commendation for the bravery of her mosaic approach and her willingness to tackle the story of a complex, controversial individual.

The winner of Australia’s other major literary prize, the Miles Franklin award, was Michelle de Kretser for her novel The Life to Come (Allen & Unwin). It is a complex narrative skipping across a number of locations, held together by wannabe novelist Pippa (her name used to be Narelle but she changed it for marketing reasons). Most of the characters have more pretensions than talents, as well as a pettiness that straddles cultural differences and generations. They see fame as an entitlement, not realising that success requires work. De Kretser walks a fine line between satirising them and indulging them, leavening the intensity of her writing with an undercurrent of humour and, in the end, affection. I do not always agree with the people who give out awards for writing but here it is deserved.

The good progress of the Australian novel is matched by the quality of the short stories being produced, judging from the pieces in Best Summer Stories (Black Inc), edited by the authoritative Aviva Tuffield. They span the spectrum from the disturbing to the laugh-out-loud, from the personal to the painful. Of particular note is Elizabeth Tan’s Shirt Dresses That Look a Little Too Much Like Shirts, a droll examination of life in the modern corporate office. Marlee Jane Ward’s The Walking Thing is haunting but the darkness is held at bay by the vigour of the young narrator. In One Hundred and Fifty Seconds, Katy Warner shows how much can be crammed into the short-story space. Corrango, by Jennifer Mills, stays with the reader precisely because so little is explained.

In politics, the past year has been one in which no-one seemed to really know what they were doing. Laura Tingle, in her Quarterly Essay Follow the Leader: Democracy and the Rise of the Strongman (Black Inc), tries to make sense of events here and in the wider world. But La Tingle sometimes seems confused about what she wants, on the one hand calling for strong leaders who will stride forward to unify their polity and at other times applauding leaders who seek to build a broad consensus before moving on anything controversial. The mention of Trump makes her splutter, presumably because he refuses to fit any traditional paradigm of leadership (and could not care less). Equally, there’s something hypocritical about a senior press gallery journo complaining that there’s too much focus on the leader. Pot, meet kettle.

The increasing strangeness of politics in underlined by Derryn Hinch’s memoir, Hinch vs Canberra: Behind the Human Headline (MUP). He is not the oddest person to win a spot on the red benches due to the peculiarities of the electoral system but he’s up there. His personal trajectory has been wild: he ran completely out of money at one point, has struggled with booze, and was jailed for contempt after naming accused paedophiles. His war on paedophiles is a constant theme running through his career although on other subjects he is all over the place. But he works hard to understand the issues and he takes the responsibility of the job seriously. So the taxpayer is probably getting their money’s worth, which is more than can be said for many other senators. Hinch pens interesting portraits of those he has encountered although his nasty streak occasionally grates. His disdain for Hanson is exceeded only by his dislike for Gillian Triggs, with whom he traded barbs in committee hearings.

Triggs undoubtedly has similar feelings for Hinch, as well as many other people. Her own book, Speaking Up (MUP), has a rather haughty tone, as she recounts her early years and her time as head of the Human Rights Commission. She thinks of herself as the defender of Australia’s marginalised people but it is not clear that she has ever met any of them. She seems mystified that anyone would question her authority, an opinion that extends to parliamentary committees. One might expect that her life would make for interesting reading but in fact the book is strangely dour. Triggs is not one for self-reflection or even acknowledging that people on the other side might have legitimate views and grievances. She has no doubts, no questions, only the certainty of her own righteousness. There is a sense of living in a bubble of people who are, well, very much like her: Guardian-world. The only interesting thing about Triggs, as a person, is that she once hoped to be a ballet dancer. Go figure.

If Triggs’ book is plodding Kevin Donnelly’s How Political Correctness is Destroying Australia: Enemies Within and Without (Wilkinson Publishing) suffers from hyperactivity. He is well-known as a newspaper columnist, and many of the short pieces in this book would be more at home in that format. His anger and conviction over the rise of the cultural Left, with its broad streak of authoritarianism and its facetious arrogance, cannot be doubted, but often Donnelly’s temper is greater than his temperance. He raises important points, especially about the influence of the Left in the education system, only to bury them as he jumps into another attack. What was needed here was a strong editorial hand to keep him focused. This is not a bad book but a cooler head would have made it a better one.

As always, competition for my not-so-coveted prize, the Trees Are Dying For This award for the most unnecessary book of the year, was strong. A contender was Clive Hamilton’s Silent Invasion: China’s Influence in Australia (Hardie Grant), an exercise in paranoid quasi-nationalism. Hamilton’s thesis is that the clever manipulators in Beijing are slowly taking over Australian politics, media and education institutions, perhaps as a prelude to a claim that the Australian continent actually belongs to China. Presumably, Hamilton is meaning to scare us but it all comes across as rather silly.

Good effort, but the TADFT has to go to The Knowledge Solution: What’s Wrong and How to Fix It (MUP). Despite an interesting introduction by Michelle Grattan on the impact of social media and the news cycle on politics, the rest of the book is taken up by re-hashes of old MUP books, many of the pieces reiterating how wonderful the Hawke-Keating era was. Really? For $30? To whoever at MUP came up with this idea, a cheap TADFT certificate awaits your collection. And if this reviewer gave a prize for the year’s most misleading title, you would have won that too.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in