Avast there, scurvy dogs! For a nation founded on piracy (the privateer Sir Francis Drake swelled the exchequer by raiding the Spanish, who were in no doubt that he was a pirate), it is appropriate that Britain should give the international archetype of the pirate his language.

The language of the Victoria & Albert’s exhibition A Pirate’s Life for Me at the Museum of Childhood in Bethnal Green is a banquet of humour and doggerel. Whether you arrive a slipperslopper sea-cook, reeking of Havanas, or pushing treasures in a pram, you will stare at walls, speak in tongues and smile.

These master (and mistress) mariners of yore have their grappling hooks deep in the psyche of maritime nations. In their infancies, modern states needed pirates. The Barbarossa brothers scourged the Mediterranean from a base on the North African littoral. Their regency of Algiers became the first corsair state until Suleiman the Magnificent made Khidr Barbarossa grand admiral of the Ottoman fleet. French corsairs — licensed privateers — inflicted magnificent damage on rival nations, retarding British trade after the Glorious Revolution; French kings received a third of the booty.

You find few such stories here. Instead, parrots, ships’ dogs, cats and monkeys, swords and antique firearms. This is what kids love, as well as the lawlessness and the silly words. And as we grow, it sticks. I honour the Jolly Roger’s signifieds: fun, freedom and mischief. Actual pirates, who I have also encountered on my travels, are different.

‘We heard screaming,’ a sailor said, in the Bay of Suez, as we were ferried off our container ships to land and safety. Recently, before armed guards were routine on vessels in the Red Sea, pirates fired from skiffs at ships’ bridges with assault rifles and RPGs — impoverished tactics compared with those of Blackbeard and John Roberts, whose mere appearance was often enough to win. ‘We heard them on the radio, screaming,’ the seafarer repeated. His ship was within electronic earshot. The screamers, the crew, might easily have been his shipmates. The shooters were not the wolfish freemen of the age of sail but ex-fishermen, almost certainly fathers and family men, their options annihilated by war, state collapse and the plunder of fishing grounds by fleets hailing from happier lands. As the film Captain Phillips documents, what is worse than piracy, now, are the conditions that create it.

‘Slash bang wallop! Waving a sword and shooting is a good way of getting people to listen to you, but what really impresses people is keeping your gun nice and shiny…’ cautions a notice in the V&A. My inner mother smiled. Dirt is a worthy foe.

The show begins in a gorgeous space: low tables, puzzles, treasure maps, clues. Blue and mauve and parrot-hung, Balthazar’s Bazar is open from 10 a.m, no licensee in sight, serving minors. Behind the bar there’s a secret passage. It teases you into its second space, a lovely dock, where a Lego schooner tilts and rides. One Golden Hind-like beauty is slyly augmented with a wind turbine astern the main mast, ensuring parents pay attention.

But where does the archetypal pirate actually come from?

Sure, Brits (and Belgians: take a bow, Hergé, Red Rackham, Captain Haddock and your translators and publishers, Michael Turner and Leslie Lonsdale-Cooper) gave him his tongue.

But whence our popinjay’s colours? His loon pants? His earrings, bee-eater gold? His sash of vermillion, shining like sillion?

Where have you seen Jack Sparrow before? From the train, beside the tracks. In the trailer park; in the lay-bys and the horse-drawn caravans of old children’s books. He is a Roma gypsy, or ‘land-pirate’ as they were called in the 17th century.

The ‘pyrate’ was introduced to the world by ‘Captain Charles Johnson’, who may have been Daniel Defoe, in his A General History of the Robberies and Murders of the Most Notorious Pyrates, published in 1724. This was the book that first press-ganged readers into knowledge of Blackbeard, Israel Hands and Calico Jack. Also of Anne Bonny and Mary Read, which left readers, unlike the curators of this exhibition, in no doubt as to the wonder and ferocity of female pirates. R.L. Stevenson and J.M. Barrie devoured their copies and scribbled out their own fleets.

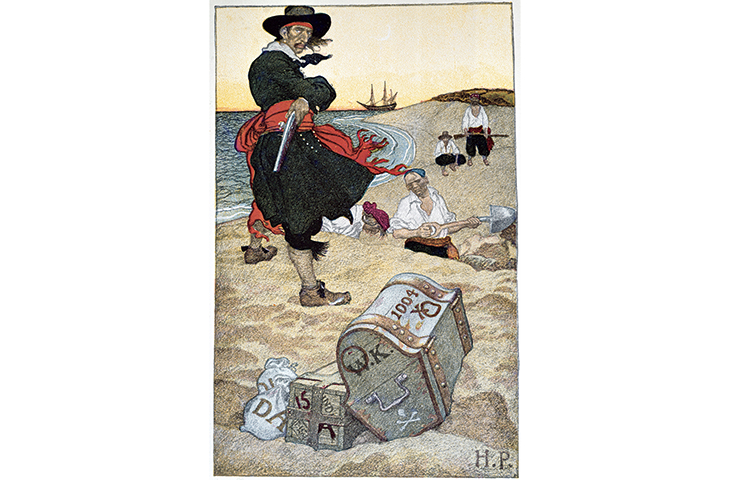

But mental pictures did not sate mass markets. So all hail Howard Pyle, admiral of American illustration, whose glowing grapeshot of sketches, paintings and portraits tore through the printed media of 1880s America, co-opting the Roma into service as western culture’s most glamorous villain. The post-impressionist pirate Van Gogh was a fan of Pyle’s work writing: ‘He strikes me dumb with admiration.’

Pyle’s America knew pirates. The US navy was formed in response to horrendous tribute and ransom demands from the Barbary states. The minister to France, Thomas Jefferson, sanctioned annual million-dollar payoffs from 1786 (each representing 10 per cent of Federal revenue in 1800). As president, Jefferson halted payments in 1801. Two Barbary wars later, British and Dutch ships supported victorious American squadrons, bombarding Algiers in 1816.

Seawolves, rovers and marooners: they have shaped the ways we picture and name ourselves, from Tiny Rowland to Red Adair.

The attractions of pirate life were multiple. Ships were not over-crewed, so conditions were better than in the navy; management structures resembled a cooperative (give or take a lunatic captain); but your chances of ending up with a parrot, a lover and a chest of doubloons were similar to an author’s of winning the Booker.

The greatest pirate who ever lived was Ching Shih. Widowed, she took over and expanded her husband’s fleet. With more than 1,500 ships she controlled more of the South China sea than the PRC does now. She beat the Chinese, British and Portuguese navies, was offered peace in 1810, married her first mate and retired. That she is invisible, and that her sea-sisters are insignificant presences in the V&A exhibition, is an ugly gap in its smile.

Few of our children will become pirates, hopefully, but there is much that they can learn from sea-gypsies. Pirates prized honour, statutes (their ‘articles’), courage, panache and innovation. One feels sure that Britannia could find work for them now.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in