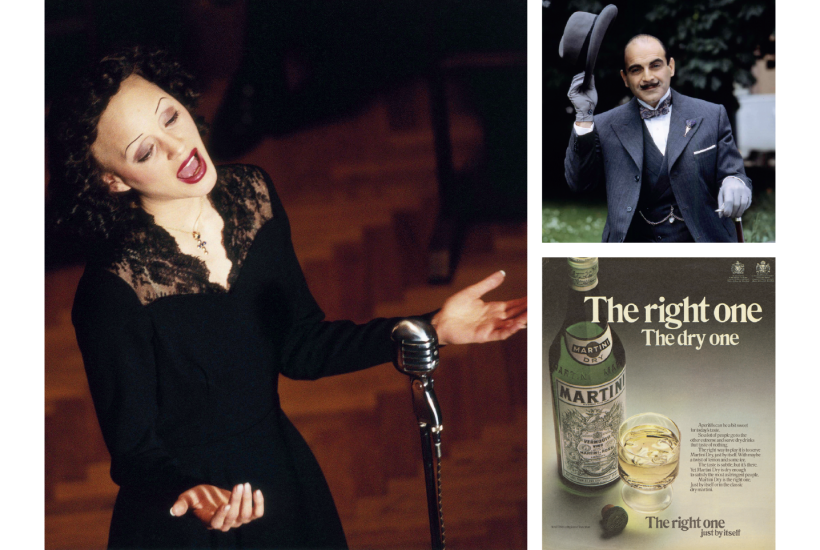

Next month in London, they’re celebrating a composer you’ve probably never heard of, but whose work you’re sure to have heard. If you’ve watched much British TV or cinema in the past half century, you’ll already know his music, and better than you think. A quick test of age: do you remember ‘The Right One’ – the song that used to advertise Martini (‘any time, any place, anywhere’) in a haze of wah-wah pedal and 1970s hair? How about Dennis Potter’s sci-fi swansong Cold Lazarus, or more recently, the Bafta-winning Édith Piaf biopic La Vie en Rose? Still no? Then...

Already a subscriber? Log in

Subscribe for just $2 a week

Try a month of The Spectator Australia absolutely free and without commitment. Not only that but – if you choose to continue – you’ll pay just $2 a week for your first year.

- Unlimited access to spectator.com.au and app

- The weekly edition on the Spectator Australia app

- Spectator podcasts and newsletters

- Full access to spectator.co.uk

Unlock this article

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in