‘If liberty means anything at all it means the right to tell people what they do not want to hear,’ wrote George Orwell in his preface to Animal Farm.

It is a line that has gone down as one of the great capsule defences of dissent, made all the more prescient by the fact that the preface, an attack on the self-censorship of the British media during the second world war, wasn’t published until the 1970s.

But the lines that follow it are too often overlooked. ‘The common people still vaguely subscribe to that doctrine and act on it,’ Orwell goes on, ‘it is the liberals who fear liberty and the intellectuals who want to do dirt on the intellect’.

When we think of dissent today, we think of the intellectuals, the liberals, the learned revolutionaries, the cultivated minds willing to ‘speak truth to power’ against state tyranny or the tyranny of the mob. We think, most often, of those who attacked the establishment from within it.

To its credit, I object, a new exhibition at the British Museum, co-curated and fronted by Private Eye editor and satirist Ian Hislop (a man as much of the establishment as a thorn in its side), reminds us that the irreverent, rebellious instinct was never limited to those of good education and supposedly superior breeding. The history of dissent is as much about the rabble as the rabble-rouser.

In a similar fashion to former British Museum director Neil MacGregor’s much-celebrated 2010 book and Radio 4 series A History of the World in 100 Objects, Hislop tells his global potted history of dissent through a series of objects and artworks — large and small, familiar and unfamiliar — gleaned from the museum’s enviable archive.

The first piece that catches the eye is not a flame-licked copy of some revolutionary tract, but a 6th-century BC Babylonian brick stamped with the name of King Nebuchadnezzar — an attempt to remind people of his greatness long after he, and his buildings, were gone. But look closer and you see another name, ‘Zabina’, carved above Nebuchadnezzar’s in Aramaic. It was the name, historians believe, of a bricklayer, keen to make his own mark on history; a cocky workman insisting he, too, was deserving of posterity.

As Hislop notes in the final instalment of the exhibition’s accompanying Radio 4 series, we have a tendency today to think of ordinary people of ancient eras as reduced to drone-like obedience by autocratic terror. But gazing on many of the objects here makes clear that the impulse to do a two-finger salute, even if it is as the tyrant’s back is turned, is more universal and transhistorical than we might usually think.

As is the human delight in smut. Close by Zabina’s brick is a shard of ancient Egyptian stone, cast aside by the men working on the tombs in the Valley of the Kings. On it, another cheeky craftsman has drawn two people going at it Anubis-style, and inscribed the words ‘A satisfied foreskin means a happy person’ in hieroglyphs. ‘It seems builders on construction sites have always been keen on sexual commentary,’ writes Hislop, in one of many speech bubbles scattered across the exhibits.

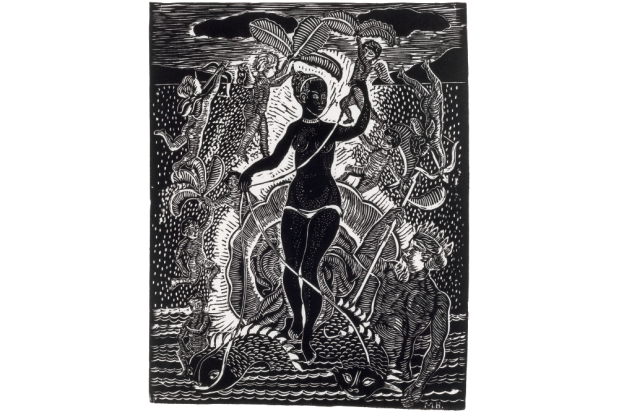

Later, as the exhibition explores the great, scurrilous caricaturists of 18th- and 19th-century Britain, we see how crucial low humour has been to dissent, and how it was as relished by our most fêted satirists as it was by the builders of antiquity. James Gillray’s 1792 print ‘A Voluptuary under the horrors of Digestion’ caricatures the future King George IV, then the Prince of Wales, as fat, tightfisted and stricken by piles. He picks his teeth with a fork, and behind him is an overflowing chamberpot pinning down various unpaid bills.

Scatalogical humour brought royalty low, insisting they were no better than the rest of us, and quite often far worse. Caricaturists of the age were a particular thorn in an HRH’s side: unlike pamphleteers, who traded in sincerity and bombast, they were much harder to prosecute, their seditious and treasonous messages were buried in irony, nods and winks. George Cruikshank was eventually bribed £100 by George IV ‘not to caricature His Majesty in any immoral situation’.

The potency of such satire lay in its — often graphically illustrated — lack of deference to authority. There was immense power in simply blowing raspberries at tyrants, or depicting their bodily fluids. It was liberating and dissident in itself.

Yet satire has also helped to push for real reform. One of the most striking works here is a beautifully intricate banknote, drawn by Cruikshank in 1819, depicting a row of people hung by the neck. It is ‘signed’ not by the governor of the Bank of England, but by Jack Ketch, a notoriously incompetent executioner. Forgery was an offence punishable by death at the time, and the bank’s roll-out of hastily made £1 and £2 notes led to a wave of forgeries met by a vicious clampdown. Many were strung up simply for handling the fakes.

The satirical note hit a nerve, and the law was soon changed. Cruikshank — somewhat immodestly — took full credit.

Dissent-by-currency is a recurring theme here. In 1968, one anonymous engraver hid the words ‘SCUM’ and ‘SEX’ in the illustrations surrounding the portrait of Queen Elizabeth on the Seychelles’ — then still a British colony — new 10- and 50-rupee banknotes. Elsewhere, a £20 note, defaced by the artist David Blackmore in 2016, declares: ‘Stay in the EU.’ But it’s a protest that feels far less anti-establishment given that it sits next to a €5 note daubed with the figure of the Grim Reaper by the Greek artist ‘Stefanos’ in 2014, at the height of the EU’s economic battering of Greece.

Indeed as the exhibition looks to objects from the past few years — the pink-cat ‘pussy hats’ from the anti-Trump women’s marches, or pro-EU badges — a certain paradox arises. When is dissent no longer dissent? How can a pro-EU protest be anti-establishment, given the EU is beloved by the establishment? How can the anti-Trump movement call itself the Resistance, when its figureheads range from former FBI director James Comey to Hillary Clinton? Have the politics of dissent been co-opted by the establishment? Hislop leaves these questions dangling.

I object is fascinating, nevertheless, and reminds us that the history of dissent does not belong to the intellectuals. The little people object, too. And as the past two years remind us, they don’t always object so quietly.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in