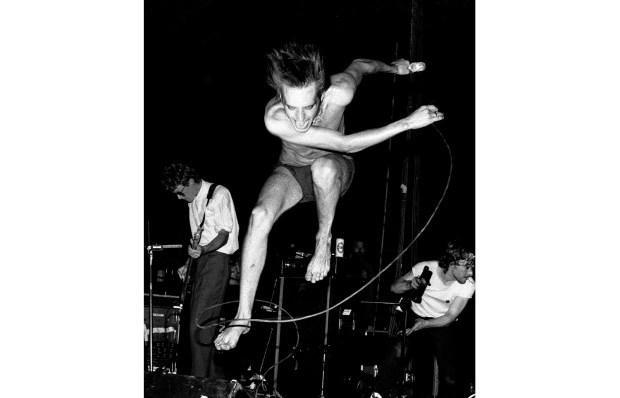

Viv Albertine, by her own admission, hurls stuff at misbehaving audiences. Specifically, when the rage descends, any nearby full cup or glass is likely to be decanted over the object of her ire. She’s remembering an incident a few years back, at a gig she played in York, when she felt compelled to introduce some persistent talkers to the contents of their pint glasses. ‘There’s such a fine balance there, because you don’t want to sound like a schoolmarm. Johnny Rotten used to walk offstage if there was spitting. The Slits [the groundbreaking punk band for whom Albertine was the guitarist] couldn’t do that because we would have looked like Violet Elizabeth Bott: “We’re not going to play until you thtop thpitting”.’ She laughs, something she does a fair bit, and it’s important to note, because her words alone make her appear fairly terrifying, to men at least.

But back to York, and the talking men. ‘So I was toying with the idea that if I said something to these cunts, am I just gonna look like a schoolmarm? But in the end, I had to shut them up, and I tried to do that in a way that wasn’t schoolmarmish, that shocked them.’

In her new book To Throw Away Unopened, Albertine recalls that incident, and the silence of the audience as a middle-aged woman confronted boozy men who were ruining a show. I’m surprised they didn’t back her up with cheers, because God knows how much we all hate people who talk through performances. ‘Yes,’ she says, surprised the thought had never occurred to her. ‘Why the fuck didn’t they cheer?’ And then she thinks of a reason. ‘Maybe they believed me when I said, “I’ll take it outside with this fucking bottle, mate.”’

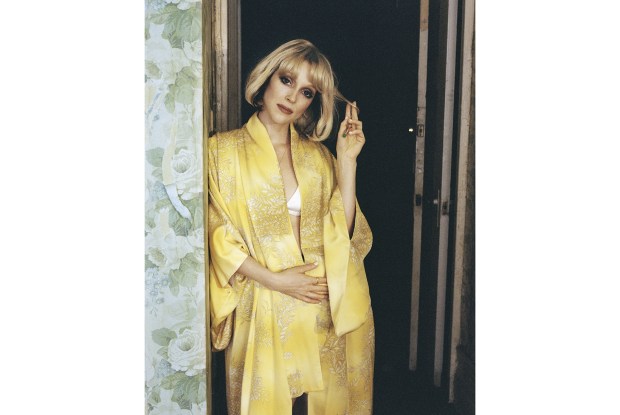

Albertine’s first book — Clothes, Clothes, Clothes. Music, Music, Music. Boys, Boys, Boys — dealt with the externalities of her life: the London punk scene, her time in the Slits between 1977 and 1982, her career and relationships after that. The new one is concerned much more with her family — her mother and father, who split when she was a child, her sister and her daughter. Of the principals, Albertine included, only her daughter escapes without a certain amount of savaging. The readers’ sympathies ebb and flow, as did Albertine’s during the course of writing it, as she discovered more about how her mother and father perceived their marriage very differently.

‘One of the questions in the book was: how the hell did I turn out to be this person who is so full of anger?’ she says. ‘To me, part of the detective story in the book is realising it was my mother who really schooled me like a little warrior: indoctrinated me, chanted and nagged me in quite a different way to most mothers.’

One would walk past Albertine in the street without thinking for a moment she was either one of the original punks, or filled with rage: she doesn’t get a second glance in the Jewish arts centre café in which we meet. Unlike say, John Lydon, she doesn’t look and speak like a caricature of her young self. She speaks precisely, and — this is probably the wrong thing to say — looks frankly brilliant for 63, despite having come through cancer and other vicissitudes. And, as the two books detail, there have been enough vicissitudes to go round, often because of her belief in living as honest a life as possible.

I say that honesty seems an awful lot more important to her than happiness. ‘I didn’t pursue happiness at all,’ she all but snorts. ‘I’ve never pursued it. I wasn’t brought up to pursue it. You’re quite a bit younger than me [I’m 48, not 23] and there was a bit more of that ethos around as you grew up. But when I grew up there was no pursuing happiness; it wasn’t talked about. Both my parents lived through a world war. My grandparents lived through two world wars. And they didn’t go around saying, “Look for happiness”.’

Gosh. We do have very different views of the world.

‘I wonder why, middle-class white man? If you go against everything that is prescribed for you in life, it’s nothing but struggle and not fitting in. And it’s never ending.’

Both books, at times, read like rebukes to those who are happy to conform; to people like me, who are naturally inclined to say yes. ‘Well, our experiences have been so different. I can understand you thinking: “I’m lucky. Society is built around people like me.” So that makes it that much easier to have the space to have a bit of happiness. But I don’t think you should see it as a rebuke.’

Nevertheless, popular culture — especially pop music — is built around the dichotomy between the creative spirit and the nine-to-fiver, and it’s built into the language of pop: the divide between the hip and the square. I explain how certain songs by Ray Davies, Paul Weller and Damon Albarn have always driven me mad — the ones in which our narrator pours scorn on the dead-eyed commuter: hang on, that’s my dad you’re having a pop at! ‘That’s kind of irresponsible,’ Albertine admits. ‘I don’t think I said it in the book, but if my daughter did ask me whether she should love an artistic life or a conventional life, I wouldn’t say, “You go out there and live an artistic life!” because there are huge consequences. It’s all very well for the Kinks and Damon Albarn to sing those songs and sneer at Mr Nine to Five, but again they’re white men, so they didn’t have it very hard.’

I imagine, by now, readers might be rolling their eyes: Oh, there goes the arsey feminist. Well, Albertine is an arsey feminist. And it’s no wonder given her experiences. When she was in the Slits, the group were frequently attacked for daring to be so different to what society expected. And ‘attacked’ isn’t metaphorical: their teenaged singer Ari Up was stabbed twice. ‘They’ — that’s men — ‘would spit at us in the street, and hit us, and threaten us with rape. We literally got threatened with rape in the streets.’ She pauses. ‘Now we get threatened with rape online.’

Still, punk left her with both a legacy and proof that all you need to do to achieve something is to get up and do it, something she thinks young women should bear in mind. A few years ago, we were both judges at a Battle of the Bands contest at the comprehensive school both our daughters attended. Three of us judges offered non-committal praise, regardless of quality. Albertine, to every group of teenagers, said: ‘You! Have! To! Write! Your! Own! Songs!’

‘I couldn’t be as hard on them as I would have liked,’ she says. ‘I would have liked to have been even harder. You’ve got one life: find your voice within it. If I was a young girl coming across someone giving me a poke up the bum like that, I’d have been pleased. Any kind of role model. Any kind of encouragement. Any kind of belief.’

So, Viv Albertine, what makes you angry these days? I think I can guess the answer, and it duly arrives. ‘A pompous man who is talking down to me. I want to kill him. It triggers all the years of it. All that has built up and is coming out in me.’ I look at the table between us. Our glasses are both empty. I’m safe.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in