The majority of Australians have now indicated their support for the principle of same-sex marriage and the Government has introduced legislation to Parliament to make it legal for men to marry other men. This is something which was inconceivable as little as two decades ago. Such is the pace of change in our world.

Already several ABC journalists are pontificating about the ‘diehard conservatives’ who are anxious to shape the legislation to protect the rights of Christians who are fundamentally opposed to this development.

For most Christians, a principle that has been followed for almost 2,000 years is to be tossed aside as one more outmoded religious idea that is past its use-by date.

I have no objection to giving to anyone the right to marry whoever they want to marry. Until recently it was illegal for blacks and whites to marry one another in South Africa. In the Deep South of the USA, interracial marriage was an open invitation for the Ku Klux Klan to turn up unannounced in the night. The liberalisation of who you can openly share your bed with is a good thing.

The decline in the power of Christian religious leaders to tell us what we can and cannot do proceeds apace and, as an atheist, I watch this decline with detachment. But I cannot help noticing that, as the right of Christians to define sacred duties and obligations declines, those of other ‘religious’ groups are increasing.

Quite recently the leaders of the Anangu people, the custodians of Uluru, decided to ban people from climbing to the top of the world’s most famous monolith.

This was explained in a recent article in the online newsletter the Conversation as follows: ‘The climb is a men’s sacred area. The men have closed it. It has cultural significance that includes certain restrictions and so this is as much as we can say. If you ask, you know they can’t tell you, except to say it has been closed for cultural reasons.’ (The Conversation, November 6, 2017).

The question then arises as to why the Anangu men have the right to define what is sacred to them while the Christian clergy are facing the steady attrition of their right to define what they hold to be sacred?

According to the website of the Aboriginal Areas Protection Authority: ‘Sacred sites are important to the cultural fabric and heritage of the Northern Territory. They are important to all Australians. They are an intrinsic part of a continuing body of practices and beliefs emanating from Aboriginal laws and traditions. …They anchor cultural values and spiritual and kin-based relationships in the land.’

‘The Authority will not tell outside people about the secret parts of the sacred sites story without consulting with the custodians.’

If Aboriginal sacred sites are ‘important to all Australians’ then why is it that the sacred religious beliefs and practices developed in Christianity over the past 2,000 years are not afforded the same respect?

On the day that the results of the same-sex marriage postal ballot were announced, several ABC news programs including the Drum and Lateline focused on the issue of the right of religious organisations to tell their congregations what is an acceptable form of marriage and various Christian leaders were forced to defend their right to argue that marriage should only be between a man and a woman.

The recent debate about the sanctity of the confession as an essential element in Catholic religious belief is another example of where we see a double standard operating. On the one hand we see a deeply held belief in the inviolate right of the priest not to reveal information he is offered in the confession box coming under increasing attack while on the other, we see an increasing willingness of government officials to allow Aboriginal community groups to claim rights to control access to public areas on secret religious grounds.

The Hindmarsh Island Bridge affair which ran and ran throughout the 1990s is a case in point.

A group of activists opposed to the construction of a bridge to Hindmarsh Island in South Australia, concocted a story that ‘secret sacred women’s business’ meant that the bridge should not be built. Millions were spent on a Royal Commission and several court cases to get to the truth. In the end a bridge was built but not before people were bankrupted and political careers were ruined (Hindmarsh Island and the Fabrication of Aboriginal Mythology by Geoffrey Partington).

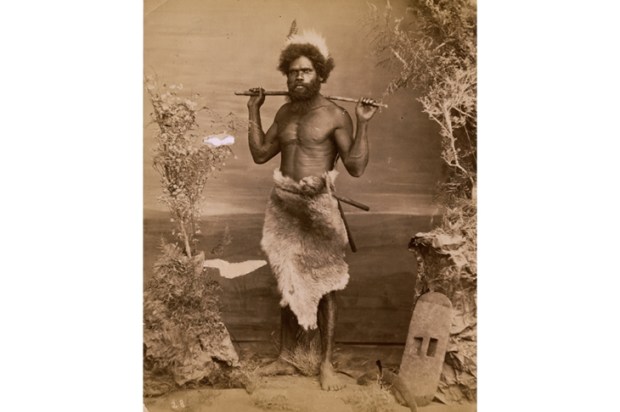

In the 19th century, missionaries destroyed traditional Aboriginal spiritual beliefs in order to replace them with Christianity. And they did a very thorough job. No one today believes that Uluru was created by two boys playing in the mud after rain or that it was a consequence of a battle between two tribes due to the presence of sleepy lizard women. Yet we are seeing a curious resurgence in the ability of Aboriginal communities to control access to what was once public land using the ‘secret sacred business’ rigmarole.

To me it seems that both the priest’s use of the confessional and the Aboriginal right to define sacred sites are more about the exercise of power and control than expressions of religious or spiritual belief. But one can also argue that all religion is necessarily about control of behaviour. After all, the job of all spiritual leaders is to tell us what we can and can’t do and so those that argue for the right of Aboriginal leaders to claim special privileges because of secret spiritual requirements must surely accept that Christians should have the same rights.

I look forward to the day when the ABC seriously questions the rights of Aboriginals to define sacred sites with the same gusto as it attacks the right of Catholic priests to proclaim their resistance to homosexual marriage. I don’t see that day coming in the near future.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in