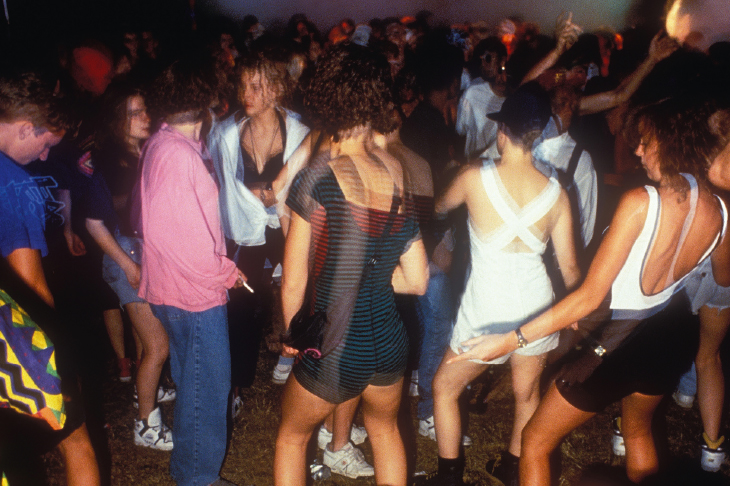

In 1988–9, British youth culture underwent the biggest revolution since the 1960s. The music was acid house, the drug: Ecstasy. Together they created the Second Summer of Love — a euphoric high that lasted a year and a half and engulfed Britain’s youth in a hedonistic haze of peace, love and unity. At the end of a decade marked by social division and unemployment, acid house transcended class and race, town and country, north and south. Amid the smoke and lasers, an entire generation came up together.

How did it happen? The story starts in Ibiza, which by the mid-1980s had outgrown its roots as a hippie commune and was attracting beautiful people from all over the world. The island’s carefree, all-night parties and eclectic music impressed a young DJ called Paul Oakenfold on his first visit in 1985. Oakenfold was determined to bring this blissed-out scene back to rainy London, with its exclusive dress codes and judgmental door policies. Although his first experiment at a Balearic club failed, another trip to Ibiza in 1987 convinced him to try again. ‘I brought a few friends over for my birthday and 30 years later we’re still talking about it,’ he says.

Oakenfold and his friend Danny Ramp-ling each started Balearic nights in London in the autumn of 1987. The Future and Shoom were wildly popular, not least because they coincided with the first major influx of Ecstasy into Britain. ‘The drugs were better than any before or since,’ says James Delingpole, an early convert. ‘Everyone was loved up in a way that subsequent generations haven’t experienced.’ The empathy-enhancing properties of Ecstasy saw people from all walks of life become best friends for the night. After years of beating each other senseless on the terraces, even football casuals were putting aside their differences and ‘getting right on one, matey’.

Noticing that their baggy-clothed, pilled-up patrons wanted to dance to repetitive beats, the Balearic DJs started playing more of the new acid-house records coming out of Chicago. The ‘acid’ in the name referred not to LSD, but to Phuture’s ‘Acid Tracks’, a record whose hypnotic, squelchy Roland TB-303 bass sound set the blueprint for the genre. ‘House’ was already the established term for Chicago’s own brand of electronic music, characterised by a 4/4 beat and syncopated hi-hat (say ‘boots, cats, boots, cats’ out loud and you’ll get the idea). It had initially found an audience around 1984 among the African-American and gay communities at Chicago clubs such as the Warehouse, or ‘house’ for short.

By the spring of 1988, a mere six months after the Balearic clubs launched in London, acid house had become a nationwide phenomenon. ‘We went from 300 to 1,500 people a night in six weeks,’ Oakenfold recalls of Spectrum, his pioneering acid-house night on a Monday at Heaven. The Trip at the Astoria, run by another member of the ‘Ibiza Four’, Nicky Holloway, was another runaway success. By the summer of 1988, shrewd young promoters were cashing in on the craze by putting on legally dubious raves wherever they could: abandoned warehouses, aircraft hangars, even a disused platform at Paddington.

One of them, Tony Colston-Hayter, found a loophole in the law by positioning his Sunrise parties as private members’ clubs. Another, Tin Tin, would ensure there was always a barrister on site to talk the police around. While many ravers considered themselves among the disenfranchised youth, these promoters embodied the entrepreneurial spirit of the times. ‘They would never have accepted it, because it just wasn’t cool, but they were Thatcherite,’ says Paul Staines, who worked as Colston-Hayter’s publicist and is now better known as the political blogger Guido Fawkes. ‘They were the first young people to have mobile phones.’

At first the media didn’t know what to make of acid house. The Sun dabbled with endorsing it in October 1988, offering readers cut-price smiley-face T-shirts, but turned on it weeks later, seizing the opportunity to whip up a moral panic. Headlines decrying the evils of Ecstasy — an infinitely safer drug than alcohol — became the norm in the tabloids. Some articles even claimed it had aphrodisiac properties that led inevitably to ‘sex romps’ on the dance floor.

Nevertheless, the party stretched on into 1989: the second Second Summer of Love. This was the year of the Orbital raves. Colston-Hayter would play a cat-and-mouse game with the police, using British Telecom’s Voicebank system to keep locations secret until the last minute. Partygoers would call a number to receive answer-phone messages that would be updated with meeting points around the M25 before the site was finally revealed. The trick was to get enough people to the rave before the police, who would then have no choice but to let it go ahead for fear of provoking a riot.

As the media outrage mounted, the police established a Pay Party Unit to crack down on the illegal raves. Helicopters scoured the countryside, and in one case frogmen were deployed to intercept a boat party on the Thames. When Graham Bright, Tory MP for Luton South, drafted a bill to increase the penalties for unlicensed parties, Paul Staines responded by launching the libertarian Freedom to Party campaign at the Conservative party conference in November 1989. It fizzled out after a few demonstrations, attesting to the apolitical ambitions of most ravers.

Rave culture lived on, initially in the form of the ‘free party’ movement. Organised by anarchist collectives such as Spiral Tribe, free parties were frequented by crusties and New Age travellers and culminated in 1992 at Castlemorton Common. This week-long gathering of up to 40,000 people in the Malvern Hills was the catalyst for Section 63 of the Criminal Justice and Public Order Bill, which notoriously banned parties of more than 20 people from playing ‘a succession of repetitive beats’ in 1994.

The great era of illegal raves may have been over, but the genie was out of the bottle. Before 1988, a night out had been about what you wore and who you ended up punching. Acid house changed this forever, reorienting leisure around music, drugs and dancing. It spawned countless musical subgenres and established DJs as godlike shamans that now sell out stadiums around the world. Electronic dance music may have started in America, but Britain was the first country fully to embrace it. From druidic ceremonies to medieval carnivals, the British have a proud history of getting off their face in a field. And what a healthy and liberating thing that is every now and then. The world has us to thank for such a gift.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in