Someone at the Buxton International Festival had a wry smile on their face when programming this year’s trio of operas. To sandwich together Verdi’s Macbeth and Mozart’s Lucio Silla — charged tales of political tyranny, both — with Benjamin Britten’s Albert Herring is a juxtaposition as canny as it is risky.

Dictatorship takes many forms, it says, and whether your choices are prescribed, your desires proscribed, by a Roman dictator or by the tweed-bosomed ‘self-appointed chief constable’ of a small Suffolk village makes little difference. But comedy is the drawing pin to the balloon of tragedy, bathos beats pathos nearly every time, and while Britten’s exquisite satire on parochial politics emerges whetted to a stiletto point, both Mozart’s teenage experiment with opera seria and Verdi’s first Shakespeare adaptation come off bloodied by the encounter.

Francis Matthews’s Herring is so overflowing with anarchic glee that it quite literally spills out from under the curtain. Before Buxton’s heavy velvet has even had a chance to rise, a couple roll out from under it, locked in an energetic embrace. It’s the first of many signs that the genteel, pre-war world of the village of Loxford survives in spirit only, whatever its lip-pursing ladies might believe.

Updated to its year of composition (1947), Britten’s opera becomes even more pointedly a tale of a community and a nation on the cusp of emancipation, preparing to seize new freedoms and bury old hierarchies in the rubble of the Blitz. Designer Adrian Linford gets in on the fun with a cleverly deconstructed set that distils the essence of Englishness — a telephone box, a country garden, a spidery conservatory — into a three-dimensional collage. A photograph of Churchill watches over Yvonne Howard’s magnificent Lady Billows, Loxford’s Lady None-Too-Bountiful, as she marshals her own forces to combat local vice and indecency.

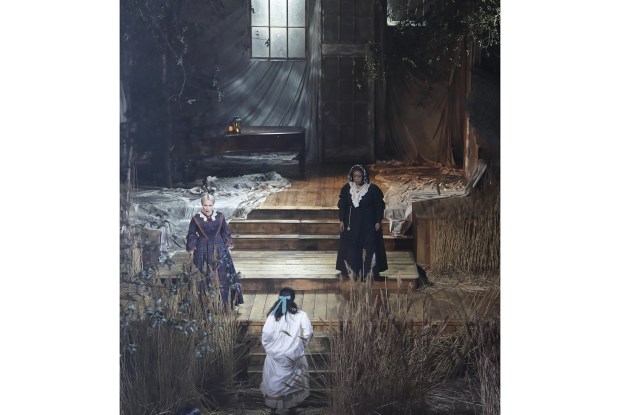

Heather Shipp as Mrs Herring (Photo: Robert Workman)

An ensemble comedy, Albert Herring is to English opera what E.F. Benson’s Mapp & Lucia books are to English literature. Each lives in the minute detail of their social observation, the affectionate dismantling of the snobberies, affectations and petty ambitions that are the pulse of their communities. From Lucy Schaufer’s brisk, embittered Florence Pike to the timid romance of Mary Hegarty’s Miss Wordsworth and Nicholas Merryweather’s fluting vicar Mr Gedge (played out in loaded quotations from the Song of Solomon) and John Molloy’s gently subversive Superintendent Budd, this is social comedy at its most lovingly, evocatively drawn.

At its heart is Bradley Smith — warmly believable as the timid Albert, who just needs a little push to break loose from his mother’s apron strings. Together with Morgan Pearse’s likely lad of a Sid (and with deft help from conductor Justin Doyle and the NCO Festival Orchestra), he gilds a character comedy with some really excellent singing, giving Britten’s satire the weight of something real and human. When he returns from his adventures, mud-stained and blissfully hungover, to face the wrath of the village it’s a revolution more powerful than any military coup.

Swords rather than snide words are the currency of Verdi’s Macbeth, performed here in its original 1847 version. In his programme essay, director Elijah Moshinsky claims greater dramatic concision and impetus for this than the revised 1865 score. But rendered in the wan colours of the NCO Festival Orchestra under Stephen Barlow (matching the sickly greens and rusty reds of designer Russell Craig’s period non-specific set) it fails to generate much tension. It doesn’t help that the chorus of witches sing like the Oxbridge choral scholars they probably are, nor that movement director Caroline Pope forces them into an ill-advised A Chorus Line-style dance routine just when they should be at their most menacing.

Which is a shame, because the central relationship between Stephen Gadd’s Macbeth and Kate Ladner’s Lady Macbeth is electric. This is murder as much for erotic fulfilment as for political gain — a twisted gift between lovers lost to the world around them. Although vocally at her limits, dramatically Ladner makes a fine villain, allowing Gadd to retain a rare humanity. Together with the muscular beauty of his singing, it makes for a hero who, provocatively, seems almost more sinned against than sinning.

Lucio Silla (Photo: Robert Workman)

But if Macbeth shows the limitations of early Verdi, it’s positively precocious when compared with Mozart’s Lucio Silla — a turgid piece of cod-classical embellishment. With Mitridate having just finished its run at the Royal Opera House, it can’t even claim to be the best opera by the teenage Mozart on offer in the UK this summer.

Playing fast and loose with classical history, the plot hardly bears scrutiny. Like the composer’s later Clemenza, it pivots to a sudden happy ending; unlike Clemenza, it feels forced and awkward, raising more than a few laughs on opening night. Faced with a score of empty virtuosity, and Linda Buchanan’s equally empty set (which resembles nothing so much as a half-finished leisure centre), a brilliant young cast and conductor Laurence Cummings do their best.

Long arias and a lack of props force them into an awful lot of pacing, but nevertheless Fflur Wyn’s sweet-toned, sweet-natured Celia, Rebecca Bottone’s imperious Giunia and Karolina Plickova’s vacillating Lucio Cinna all make their mark musically. After an uneven start Madeleine Pierard’s Cecilio settles into some superb coloratura, and in the title role tenor Joshua Ellicott has great fun giving the audience his Richard III, with a little Mozart on the side.

An empire is won and lost in the course of the opera, but the tension, the intrigue, the power play don’t compare to the machinations of Lady Billows and her fellow Loxford residents. Definitely one for the once-is-quite-enough pile.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in