‘I frequently went to bullfights with Picasso,’ Sir John Richardson remarked, quite casually, as he showed me around the exhibition Picasso: Minotaurs and Matadors, which he was installing at the Gagosian Gallery, Grosvenor Hill. He mentioned this by way of explaining why a large and splendid linocut was inscribed to him by the artist: ‘à mon cher ami.’

They saw many fights together in the 1950s, either in Nîmes or Arles. Picasso took these occasions seriously. ‘If the fight was going well he was silent, concentrating totally. What he couldn’t stand was people talking. He would sigh and say, “Oh, I wish they’d shut up.” All around him people were shrieking if something went wrong, but he was absolutely cool as can be.’

Picasso was an aficionado, an ardent devotee of the sport; similarly, Richardson himself is an aficionado of Picasso, combining vast knowledge of his work with an intimate day-to-day acquaintance with the artist, a sense of how Picasso thought and felt. It is now 37 years since he embarked on his immense Life of Picasso, of which three volumes have appeared to date (the third taking the narrative only up to 1932).

Richardson was drawn to the work even before he encountered the man. At 14 years old, still a schoolboy at Stowe, he saw a copy of ‘La Minotauromachie’ (1935), at Zwemmer’s bookshop on Charing Cross Road. Now regarded as Picasso’s greatest print, this etching was then recent and priced at £50. He asked his mother for an advance on his allowance to buy it, but instead she gave Mr Zwemmer a dressing-down: ‘It’s a disgrace trying to palm off this stuff on children!’

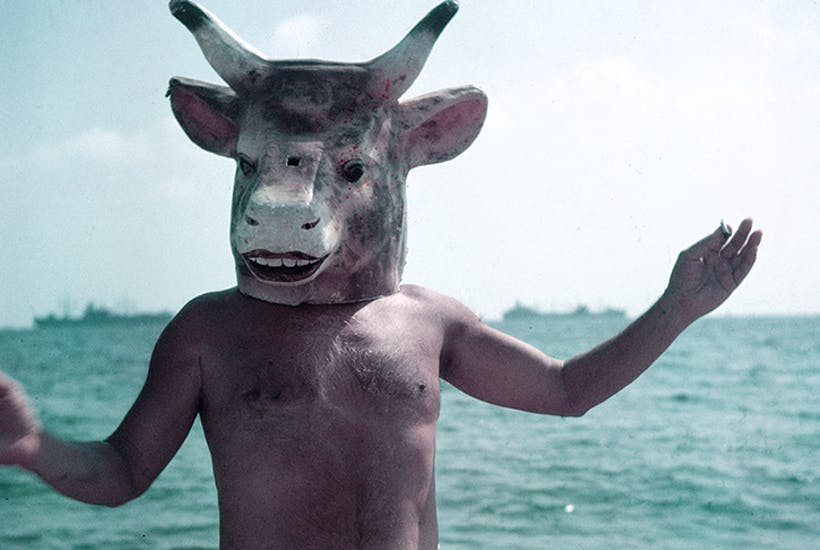

The minotaur, like the bullfight, was a frequent theme in Picasso’s art. Together these two interlinked subjects — the bull-man and matador killing the bull — make up the Gagosian exhibition. Both are deeply connected with Mediterranean culture, going back to ancient Crete, and also with Picasso’s psyche. As Richardson points out, the artist seems to empathise now with the bull, now with the matador, and often with the Minotaur. Did Picasso identify with this horned and hirsute monster? ‘God, yes!’

The Minotaur is now a hero, now a villain. In the great ‘Minotauromachie’— all seven magnificent states of which are on show at Gagosian — he brandishes a sword. At other times he reclines with a naked girl — amorous, if alarming. In another incarnation, the Minotaur is blinded and led by a young girl.

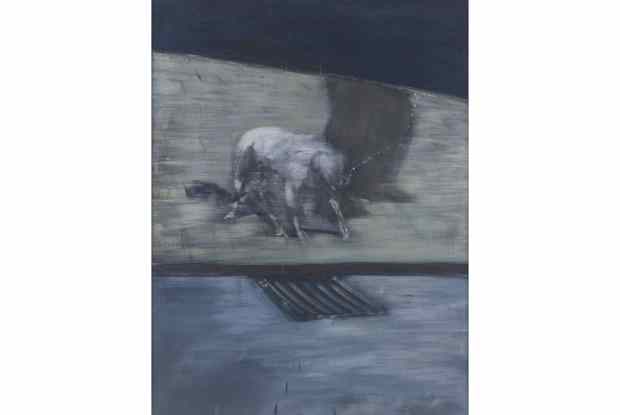

At 93, Richardson has now outlived his subject, who died in 1973, aged 91. Like Lucian Freud — a contemporary and good friend — he has the disconcerting attribute of seeming to have known absolutely everybody in 20th-century art and literature. Picasso is not the only great painter about whom he has written; in the 1950s he concentrated for a while on the other progenitor of cubism, Georges Braque (‘It was much more difficult than becoming a friend of Picasso; Braque was very reticent’) and in British art knew not only Lucian Freud but also Francis Bacon.

Richardson met the latter in the mid-1940s when he was little more than a rumour, having scarcely exhibited. ‘There’d been one illustration of an early Bacon in a book by Herbert Read. I and many of my friends worshipped this plate, but none of us could find out who Francis Bacon was.’

It turned out he was living on Cromwell Place near the Richardson family home. ‘Looking out of the window, I used to see this youngish fellow carrying paintings, and somehow I guessed he must be the mystery man.’ Bacon, too, became a good friend; subsequently, Richardson had the unusual experience of living with some of the furniture that Bacon designed as a young man, and which was owned by Richardson’s partner during the 1950s, Douglas Cooper.

These were among the least attractive items in an extraordinary array of modernist art owned by Cooper, with the main emphasis on Picasso. ‘It was a very intelligently put-together collection. Douglas had paintings, small sculptures, an enormous amount of drawings and works on paper, complete sets of prints. He was well-off, but he wasn’t that well-off, even though Picassos were fairly cheap when he was buying. He had a great eye, my time with him was a fantastic apprenticeship.’

Cooper also possessed a famously abrasive personality. George Melly described physically throwing Cooper out of the art gallery where he was working, the latter’s offence having been to walk up to some clients who were about to make a purchase and hiss, ‘Don’t buy it! It’s rubbish!’

Richardson was warned by Bacon against having anything to do with Cooper. But he disregarded the advice — fortunately, because, despite the difficulties and rows, his years with Cooper were formative. How else could an English 26-year-old have stepped, as he did, straight into the inner circle of the world’s most celebrated artist?

Richardson visited Picasso’s Parisian studio in 1949, shortly after he began his relationship with Cooper. ‘Picasso used his huge eyes as a hypnotist might, raking the room for possible subjects,’ he later wrote. ‘At one moment he turned his eyes on me and held my gaze for long enough to induce a responsive quiver.’ Thus biographer and subject first met.

A few months later, while touring the Provençal countryside in Cooper’s ancient Rolls-Royce, they came across a deserted mansion, surrounded by columns. ‘There was a big notice on one of the columns saying, “Château à vendre.” Douglas exclaimed, “My dear, I’m going to buy it!”’ Richardson’s voice takes on a zestful rasp as he repeats these words.

This mansion proved the perfect setting for Cooper’s superlative collection. As it turned out, Picasso also felt it was perfect. ‘When he saw it he exclaimed, “I want this house! I’ll give you three major works for it.” Douglas said no.’ During the 1950s Picasso was living not far away on thecoast, first at Vallauris, then Cannes.

‘On one occasion, Picasso tested us. He invited us to visit him before Christmas. He showed us a series of drawings on big sheets of paper, profiles of a girl. There were 12 of them, very, very strong, in black-ink wash. Picasso said, “OK, these are your Christmas presents. You choose.”’

‘I chose the strongest and simplest and most basic one. Douglas selected the most elaborate: it had little frills, and bits added here and there. Picasso said, “Right, that’s yours.” Then he added, “Douglas, I don’t think it’s quite elaborate enough for you. I think I’m going to…” And he took some coloured crayons and started completely fucking it up. I exchanged a look, almost a wink, with Picasso as he did these things.’

The artist would always come over to visit for major bullfights. Afterwards, there would be a picnic dinner in the garden of Cooper’s château. ‘Picasso would come with his entourage, we’d round up cowboys from the Camargue and the matadors. In no time people would be dancing around. Picasso was absolutely happy. With him bullfighting was like football is for some English people: a lifelong obsession. It was in his blood.’ Just as, after all this time, Picasso remains in Richardson’s.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in