Why set a supremely great play to music? The Winter’s Tale, the play of Shakespeare’s that I love most, has much of his most beautiful and intelligent poetry, as well as some of his most condensed and puzzling lines. Ryan Wigglesworth, in several of the innumerable interviews about his new opera, says he has been obsessed by the play for decades. So have I, but if I were a composer I think that would be a reason for leaving well alone. Wigglesworth has made his own libretto by using snippets of Shakespeare, enough to remind one of the original, but frustrating, most of the time, in producing a strip-cartoon version of the text. The idea, presumably, is to amplify this telegrammatic digest with the music. But, though I found the textures of the orchestra continuously interesting, much of the time, especially in Act I (which covers Shakespeare’s first three acts), I wasn’t able to see in what relationship they stood to the words and the action.

I shall certainly go to another performance of the piece, mainly in the hope of changing my mind. First time round I was unable to feel anything with or about any of the characters, apart from odd moments. When the unjustly accused Hermione, gloriously sung and acted by Sophie Bevan, uttered one of Shakespeare’s most desolate lines, ‘The flatness of my misery’, I knew what I was missing most of the time: the line is set to a low monotone, almost spoken, and left as Shakespeare wrote it — unlike, for instance, Florizel’s sublime speech to Perdita, of which we get fragments. I could have forgotten my reservations about the earlier parts if the final scene, with Paulina unveiling the ‘statue’ of Hermione and bringing her back to life, had been moving. Only the composer of The Magic Flute could have found music adequate for this scene, but that suggests that anyone else is foolish to try. The opera peters out rather than coming to a radiant close.

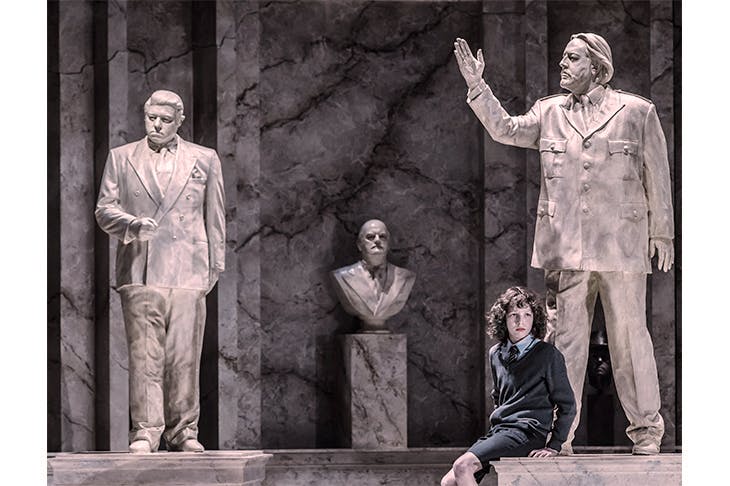

The production is by Rory Kinnear, another operatic tyro. It seems to be set around the middle of the last century, Leontes and Polixenes are two fascist dictators, with plenty of alarming salutes from their subordinates, and from the non-Shakespearean chorus which provides the opera’s most thrilling moments. I see no benefit in this updating. The set is impressive, with revolving curved walls that close for scene changes and disintegrate at the end of Act I, when we see a little boat aloft, with Antigonus and the baby Perdita.

The cast is as strong as one could wish, though none of them has the time or music to make their characters intelligible. Iain Paterson sings his curt lines imposingly, his Leontes a shambling bewildered figure, while Leigh Melrose, his fellow dictator, is smooth and crisp. The great Susan Bickley makes what she can of Paulina, but Shakespeare’s termagant, whose essence is uninterruptable eloquence, is reduced to a handful of lines which make it impossible to show either her determination or poignancy. The young lovers Perdita and Florizel are caught in their ingenuousness but not in the miracle of their poetry, by Samantha Price and Anthony Gregory. The large orchestra, ejaculatory and explosive in Act I, softer and warmer for the most part in the other two acts, plays with all the eloquence and occasional expressiveness which the composer-conductor could hope for. It will be fascinating to see what second impressions will yield.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in