As you go into the new Wellcome Collection exhibition, Electricity: The Spark of Life, you might have in mind a sentence from Mary Shelley’s original electrifying novel Frankenstein; Or, the Modern Prometheus: ‘I collected the instruments of life around me, that I might infuse a spark of being into the lifeless thing that lay at my feet.’

A copy of the 1831 edition of her book, with its startling anatomical frontispiece, awaits you, among many other wonders. The exhibition, a collaboration between the Wellcome, the Teylers Museum of Haarlem and the Museum of Science and Industry, Manchester, is packed with electrical instruments, together with models, artefacts, books, film loops and pictures. It displays a vast historical panorama dating from the ancient Greeks — a terracotta plate from Campania showing an electric torpedo fish, 630 BCE — to the late 20th century, with a sporty two-minute movie of pioneering electric cars from the 1960s.

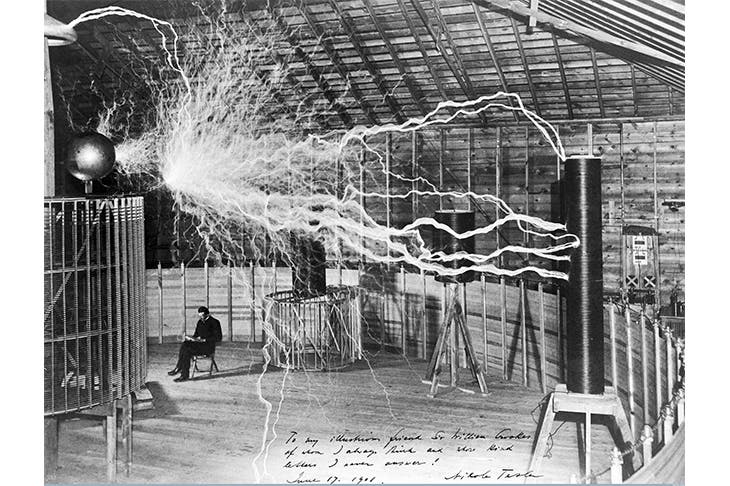

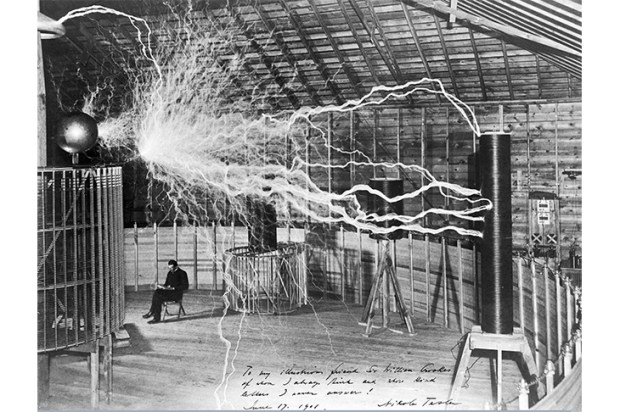

Yet your first impressions might be a bit muted, a bit low-voltage. Despite the sparky promise of the title, the danger is that nothing much will actually light up; that there are no great euphoric flashes, no cheering gleams or sinister glows. There is a Cuthbertson electrical discharger of 1800, consisting of two brass and copper globes mounted side-by-side on an insulated mahogany stand, but you will wait in vain for an actual spark to crackle between them. There is also a Martinus van Marum electrostatic generator of 1787, capable of discharging 300,000 volts and producing a two-foot spark, but it is only a fold-out illustration. There is an original Edison carbon filament incandescent lamp bulb from 1879, but it does not switch on. There is even an Archer electric kettle of 1900, but it does not boil.

However, as one of the dedicated curators, Ruth Garde, shrewdly admonished me, you would be wrong ‘to switch off your own imagination’. The Wellcome exhibition obviously aims at a different kind of illumination.

The essential approach is historical and explanatory: the history of a developing technology and, more subtly, that of an evolving idea or dream.

The great early scientific question was this: what did the extraordinary invisible power called ‘electricity’ (from the Greek, elektron, meaning amber, which you rub to release this mysterious stuff) actually consist of? If you think you know the answer to this, try explaining it clearly to a sceptical child — not what it does, but what it is. By the 18th century, various different explanations and types had been identified. Obviously, there was lightning. Then there was ‘animal electricity’. Electric eels, for example, could produce a lethal 6,000 volts. A dramatic engraving illustrates the terrified rearing horses being used in a river to discharge these deadly shocks, as recorded by the explorer Alexander von Humboldt in South America.

From the mid-18th century there were electrostatic generators, made from rapidly revolving discs or globes, based on the friction principle (the same principle as running a comb through thick, soft hair).

Finally, there was the great scientific breakthrough, Alessandro Volta’s neat and ingenious chemical pile, invented in 1799. This used a series of small zinc and copper plates, stacked together like playing cards and immersed in a bath of weak acid, to produce something quite new: a steady supply of chemical electricity, through a ‘live circuit’ with two poles, negative and positive.

These early voltaic piles, which in principle and size were very similar to the modern car battery, would eventually produce the electrochemical revolution in Britain, both practical and theoretical, pioneered first by Humphry Davy, and then developed by Michael Faraday (using electromagnetism) and James Clerk Maxwell (using pure mathematics).

A strange and influential series of experiments in the 1790s by Luigi Galvani explored the difference between ‘animal electricity’ (supposedly bringing back to life the kicking legs of a dead frog) and chemical electricity.

Galvanism was soon followed by the risky experiments of Giovanni Aldini, who in 1803 performed a notorious public experiment at the Great Windmill Street surgical theatre, London, attempting to bring back to life an executed criminal, George Forster. He used carefully applied high-voltage electricity charges to the dead man’s spine, rectum and heart. Reportedly, ‘One eye opened.’ Aldini wrote a book about his experiments, Galvanism (1804), whose hideous illustrations are displayed. He spread the idea that ‘animal electricity’ in the human body could be considered as the fundamental ‘life force’ and even perhaps the ‘soul’ itself. This initiated a great ‘vitalism’ debate among the surgeons, natural philosophers and poets of the day. From all this, Mary Shelley’s own literary experiment, Frankenstein, emerged in a small, anonymous edition of 1818.

Shelley’s novel had innumerable literary and theatrical spin-offs, such as the Drury Lane melodrama Presumption; or, the Fate of Frankenstein (1823). The stage directions indicate electrical explosions and flashes from a hidden laboratory at the back of the set, and Mary Shelley herself records how ‘hubbub ensued’ in the audience, and many women fainted.

The idea of sinister scientific menace, balanced against beneficent power and potential, runs throughout the exhibition, as symbolised by a photo of the original Sing Sing Prison electric execution chair (c.1950), set against an original example of a late-19th-century ‘electrotherapeutic chair’, in comforting mahogany and purple velvet. Both were designed to cure, so to speak, a whole panoply of human ills. A similar dilemma is presented by a display of international pylon designs — so different in France, or New Zealand, or Canada — but each trying to face up to the same uneasy question: boon or blot on the landscape? Or necessarily both?

Electricity was nowhere more genuinely liberating than in the modern kitchen, and the tea towel celebrating the ‘Electrical Association for Women’ makes its sober domestic point alongside a hilarious clip of Buster Keaton’s The Electric House (1922). Some 20th-century domestic applications were wildly speculative. They include ‘a woman modelling the latest permed hairstyles’ (1923), with a huge crown of gleaming overhead cables attached to her skull, halfway between Ridley Scott’s Alien and Heinrich Hoffmann’s Struwwelpeter.

We also learn in passing the curiously provoking fact that Bovril (love it or hate it) was originally marketed as the essence of cows (‘bov’) containing a mysterious energy element (‘vril’). It turns out that the latter term was lifted from an entirely imaginary electrical substance, Vril, invented by Edward Bulwer-Lytton in his science-fiction novel The Coming Race (1871).

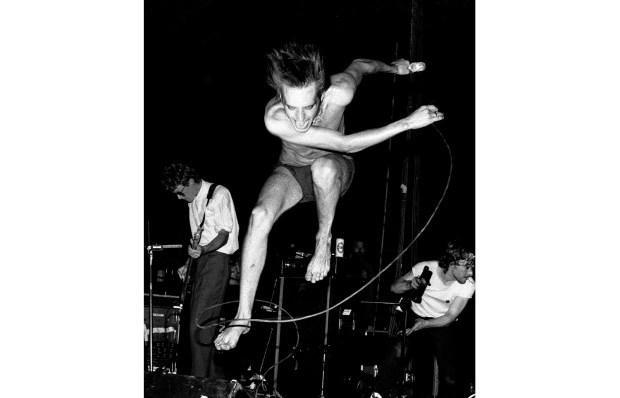

Electricity has had a sparky life in literature. Coleridge went to Davy’s lectures to renew his stock of metaphors. Keats defined imagination as Negative Capability. Walt Whitman’s euphoric poem from ‘Leaves of Grass’ (1855) begins, ‘I sing the body electric’, and virtually defines a new idea of personal liberty. These, too, are part of the electrifying story.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in