This book kept reminding me of Robin Williams in One Hour Photo. Just as his character spied on customers’ private lives while developing their pictures, so Chris Paling gets to know the readers at the library where he works. Unlike Williams he doesn’t follow them home at the end of the day (in fact some of the female librarians have the opposite problem), but Paling’s anonymous, functional role lets him observe without being observed. He sees the woman with two small children who takes out Is Daddy Coming Back in a Minute?, explaining sudden death to children in words they can understand. The ‘effete, shaven-headed man in a well-cut suit’ who angrily discusses his new shrink on his mobile phone. The woman who snaps at her husband to hide the tube of Anusol he’s just bought, then orders: ‘Now choose your books.’

What makes Paling so suited for the role is his career as a novelist. Transferring the ‘show don’t tell’ rule to this work of non-fiction, he simply reports on events and lets his material do the work. We meet the regulars, from the table-seeking students who surge in as the doors open ‘like a crowd at a Harrods sale’, to Mrs Stone, who ‘resembles both in sight and odour a compost heap over which a tarpaulin has been thrown’. She’s returning French Women Don’t Get Facelifts: Aging with Attitude. There are several wonderful appearances by Trish, one of a group of adults who attend the library every week with their carers. On one visit she points at a Kiss CD, its cover showing the band in their usual make-up, and asks Paling: ‘Is he a cat?’

Much of the dialogue is worthy of Alan Bennett. A woman states she’s been a library member ‘for donkey’s horses’. A man describes someone he knows as ‘an habitual turps-nudger’. Another is pleased about having remembered his glasses: ‘Luxury. Being able to see. Like getting an extra roast potato.’ In fact, at one point, Bennett himself is quoted: ‘I have always been happy in libraries, though without ever being entirely at ease there.’ As Paling points out, ‘It’s hard to envisage anywhere that Bennett would ever feel entirely at ease.’

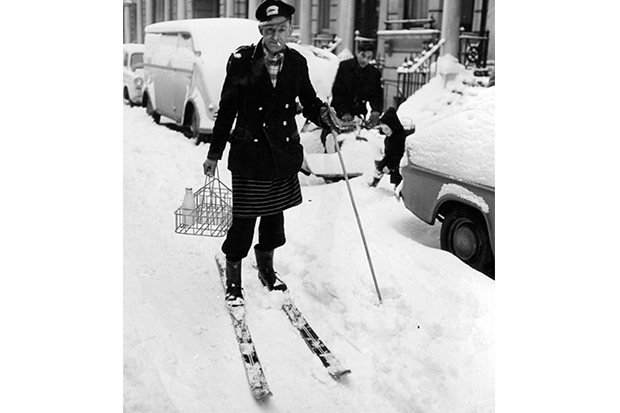

We’re also taken behind the scenes. Staff empty the overnight returns box with caution — ‘you never quite know what you’ll find in there’ — while the ‘grey-faced, cadaverous man’ who delivers the boxes of books each day would, in another life, have been ‘the collector of corpses for a funeral director’. Trev from Facilities faces regular challenges: ‘“Jumpers! How do you get a jumper down a toilet?”’ One morning several of the staff are nursing hang-overs, ‘which is perhaps why the xylophone hammer has gone missing in Children’s’.

Many of the customers are rude and selfish. Lurching Betty, for instance (‘physically, she brings to mind John McCririck, fully blinged’), who pushes to the front of the queue. Paling displays superhuman levels of patience, always wanting to cut the public as much slack as possible. ‘Mr Jones is an unsympathetic character,’ he writes of one regular, ‘but perhaps deserves sympathy. He’s isolated and wages wars with his neighbours and the council. The war in his head will go on until somebody helps him to win it.’ The librarians often assist those using the computers. One man is typing his CV, in which there is a gap of nine years. ‘I’m tempted to ask the reason,’ writes Paling, ‘but I don’t because I think I already know the answer.’

Peppering the narrative are bookmarks left by readers in the volumes they return, such as a shopping list on the back of a receipt: ‘Bread, quinoa, rice, bank, teeth.’ There are also stories from libraries around the world. At least three US states have banned Fifty Shades of Grey, while in the 1990s California introduced ‘multicultural crayons’ for use by children as they drew people — each box contained more than a dozen colours ‘designed to more assiduously resemble different racial tones’.

But my favourite fact concerned the writer Edgar Lustgarten, who died of a heart attack in December 1978. Some (such as Richard Ingrams) maintain that he was walking along the street at the time, but let’s stick with the version that says it happened in the reference section of Marylebone Library. Why? Because according to that account Lustgarten went out reading The Spectator.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in