The last ten minutes of any Don Giovanni tell you more about a director than the previous two hours. Mozart’s elastic ‘dramma giocoso’ can take a lot of pulling about, can be stretched taut into tragedy or squeezed into the tight confines of a farce, but whatever option (or combination of options) you choose, those final moments are the test of success — the point at which the dramatic threads either sag, snap or hold firm. Oliver Mears’s production — first seen at the Bergen National Opera and now at NI Opera in Belfast — lets them fall limp. Seemingly unsure which choice to make, he makes no choice at all, leaving us with an ending that isn’t so much elusive as it is evasive.

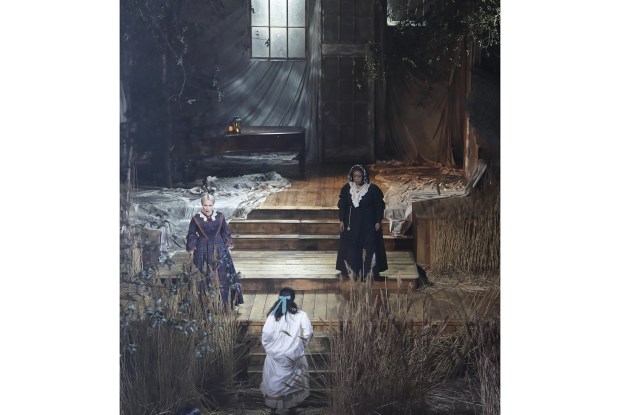

This is a Giovanni played for laughs, a frothy operatic sitcom set on the cruise ship The Seville in the early 1960s. Women frolic in candy-coloured chiffon negligees and men preen in polo necks and velvet jackets as they all flirt with sexual liberation and one another. The atmosphere is heady, Annemarie Woods’s art-deco designs are sleek and Amanda Holden’s English translation is witty (when you can understand it — surtitles are not provided), so why does it all feel so unengaging?

Perhaps it’s the psychology of the thing. Characters come in and out of focus, painted in haphazard brushstrokes that are lost in Mears’s clutter of ideas. Giovanni is a polyester playboy with a bleached-blond quiff for a personality, who finds a convenient stage and microphone from which to croon ‘Là ci darem la mano’ to waitress Zerlina. And that’s the (plastic) key to this hero; it’s all a karaoke act, a second-hand performance. He kills casually, with no conviction, but later breaks out into violent rage when he finds his seductions thwarted by Elvira. Why? We don’t know. It’s just one of many moments of interest Mears never follows up — Leporello’s sexuality, Zerlina’s pregnancy, the colonial-themed fancy-dress party that collides a blackface cartoon character with Donna Anna’s Queen Victoria and Don Ottavio’s Lawrence of Arabia.

Helped by some exhilarating speeds from Nicholas Chalmers’s pit, the action romps along happily enough for most of the evening, saying little that’s new but phrasing it nicely enough. Then we arrive at the climax. A comic Don Giovanni presents particular difficulties when it comes to the moral of the closing ensemble, the meaning we’re supposed to extract. Cutting it or undercutting it are classic options, but Mears favours neither, preferring to play things straight. You might as well end an episode of Are You Being Served? with a morality play. It’s the punchline to the wrong joke, and just doesn’t work.

In Henk Neven (imported from the original Bergen cast) the show has a hero who’s vocally underpowered and dramatically under-projected — a hole where the opera’s emotional motor should be, and no amount of by-play with bathing-suited dollybirds or John Molloy’s Leporello can redeem matters. There’s neither tension nor chemistry with Hye-Youn Lee’s Anna, whose brittle timbre threatens to flatten out the musical complexity of this curious character, and Rachel Kelly’s lovely mezzo is denied its most interesting colours in the soprano role of Elvira. Aoife Miskelly’s Zerlina fizzes with charm, however, Sam Furness (a single-aria Ottavio) once again impresses with his characterful tenor, and Clive Bayley finds plenty of craggy ferocity in the Commendatore. This is Mears’s last show with NI Opera. Next March he takes up his new role as artistic director of the Royal Opera. It’s too early to tell which way that ship will sail, but if The Seville is anything to go by it may need a little help getting out of harbour.

‘For who can wield like Shakespeare’s skilful hand?’ was the unfortunate subtitle for Bampton Classical Opera’s Shakespeare 450 tribute at St John’s Smith Square. Unfortunate because the implied answer (‘No one’) was so clearly at odds with the material on offer. There was no Shakespeare here — not a single couplet — just two works of gawky, fanboy homage from Georg Anton Benda and Thomas Linley the younger, nicknamed ‘the English Mozart’.

Neither Benda’s Romeo and Juliet nor Linley’s Ode on the Spirits of Shakespeare have much claim on a contemporary audience — a rare misfire for a company with a good nose for a musical rarity. Benda’s singspiel was here reduced to extracts, and Friedrich Wilhelm Gotter’s Shakespeare-inspired libretto translated back into less than Shakespearean English by Gilly French and Jeremy Gray. The result was like a Mozart pastiche composed by Sullivan, its flimsy charms struggling to survive this under-rehearsed performance. The Linley (a magpie score drawing on Mozart, Handel and Purcell, among others) was stronger, but still scarcely worth the bother.

Imitation may be the sincerest form of flattery, but when it comes to art sincerity just doesn’t cut it. Shakespeare and Mozart said it best; we’d do better just to let them get on with it.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in