For much of the Middle Ages, especially from 1250–1350, ‘English work’ was enormously prized around Europe from Spain to Iceland. Popes took pains to acquire it; bishops coveted it; the quality was such that the remnants have ended up in the treasuries of Europe. London, especially the area around St Paul’s, was famous for its production. And what was English work? Embroidery, that’s what. Beautiful, costly, high-quality embroidered pieces, much of it using gold or silver thread, sometimes embellished with pearls and precious stones. Matthew Paris tells a story about Pope Innocent IV spotting some English bishops wearing lovely vestments and badgering them to find some of it for him, preferably for the lowest possible cost. The point of the story was the pope’s acquisitiveness; what it also makes clear is that English work was conspicuous for its workmanship and beauty.

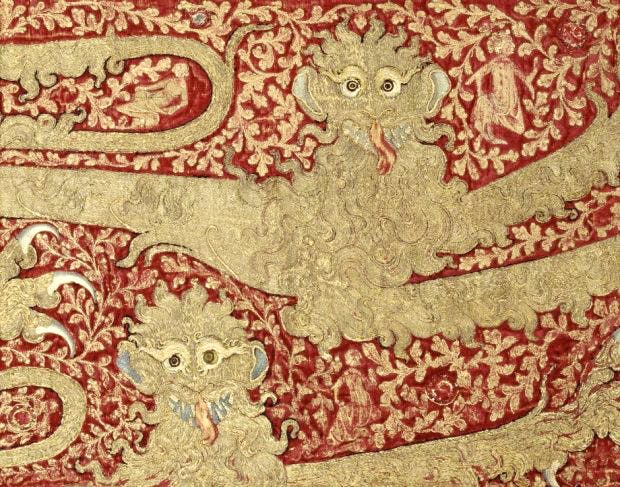

The last exhibition of Opus Anglicanum was 50 years ago; now the V&A is giving this generation an opportunity to see for itself pieces that have been assembled from around Europe from the 12th to the 16th century — though the catalogue observes that Anglo-Saxon embroidery was hot too. It’s a wonderful collection, mostly liturgical vestments — copes and chasubles that the priest or bishop would wear at mass — but including some secular pieces. What it should do is put embroidery in its proper place as an art form alongside stained glass, floor mosaic, painting and manuscript illustration, with which it shares exactly the same artistic form and imagery. There’s one lovely embroidered panel here of poor St Hippolytus being martyred which has grotesque figures at the top — animals with leering human heads — that are identical to those you find in the margins of manuscripts of the same period.

Yet, obviously enough, embroidery, and needlework generally, has never had quite the same recognition as those others, perhaps because art historians were chary of it, partly because the material is uniquely vulnerable to the effects of light and time, and partly, perhaps, because needlework is seen as women’s stuff.

Certainly women did take part in the production of English work (the term was generic; for obvious reasons it wasn’t used in England), though probably not as designers so much as needlewomen. It’s likely that some workshops were mixed. The pay rates reflected skill, with the draughtsmen getting eight pence a day in 1330, and needlewomen just over twopence. The exhibition, and website, usefully includes a video of couching, the technique whereby gold thread was attached to cloth by understitching, barely visible on the surface, and split-stitching, which allowed the embroiderer to follow the contours of the shape they were filling in, like brushstrokes. The skill was extraordinary. From the end of the Black Death up to the 16th century, techniques changed, and sometimes figures were sewn on to a backdrop, having been completed elsewhere.

The problem with the material is starkly apparent. Colours fade on fabric and thread far more markedly than they do on any other medium, especially black, blues and greens. Reds are OK, but the patchy survival of one colour group over the rest gives an unbalanced composition. I’d like to have seen a reconstruction of what at least one piece would have looked like originally — brilliantly garish, just like so much other work of the period. The ravages of time have given us — as in cathedrals — an altogether false idea of medieval taste, which liked colour, gold and silver, and lots of it.

The thing about these objects is that they were intended for use. Yet most of the fabulously elaborate decorative scheme on, say, the Madrid cope (c.1300) — unique in its cycle of Old Testament stories, including the Creation (when God creates animals, he includes a unicorn) — would not have been visible to the congregation looking at the vestments at mass or in procession. You’d have seen the crucifixion strategically placed on the back, with glimpses of the rest. So the notion that these decorative schemes were somehow stories in stitches for the unlettered doesn’t wash. These things could be seen in their full glory by only a few people, including their makers — and God — though they’d still have been beautiful to behold.

What this exhibition makes abundantly clear is that right up to the Reformation, there were wonderful embroidered pieces being produced in London, though few survive. The most impressive may be the pall for the Fishmongers’ Company — guilds sent their members off to their eternal rest in style, their coffins covered with the guild pall — complete with mermaids, angels and merknights. It’s an object for use, display and of craft pride.

It wasn’t just moths and light that took their toll on similar pieces. The iconoclasts of the Reformation — Thomas Cromwell’s commissioners and their successors — gave the vestments short shrift when they made their inventories of church possessions; many were wilfully destroyed, or melted down for their gold. Bastards.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in