It’s funny, isn’t it, how a dust jacket on a book can draw you to it from the other end of a room — always supposing the illustration is by Edward Ardizzone. In fact, is there anything more suggestive of delight than a book illustrated by him? It’s the Midas touch even for unprepossessing authors. The exhibition of his work at the House of Illustration finishes off with a wall lined with them: The Little Grey Men, Jim at the Corner, Italian Peepshow, Johnny’s Bad Day, Eleanor Farjeon’s Book… you’ll recognise lots.

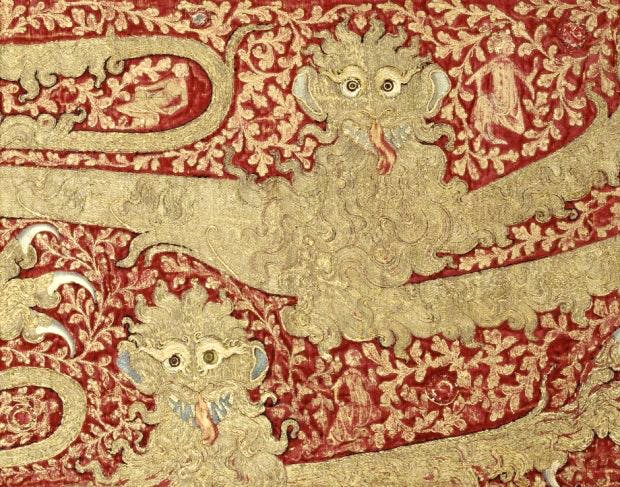

And there’s something utterly distinctive about every one: the boy’s upturned nose, the rounded line of a motherly woman’s bottom — he’s good at soft women’s lines; the tapering narrow shins of two children in Edwardian dress; the curve of a dragonfly’s body over a pool where a dwarf with a wooden leg sits fishing. Just a line, usually a curved line, but evocative of a delicacy and humanity that characterised everything — well, nearly everything — he ever drew. Actually, there’s a dragon in this exhibition that he did when he was a boy, and it’s reminiscent of the feisty, fierce one in what is, I stoutly maintain, his masterwork: The Land of Green Ginger, Noel Langley’s wonderful tale of dragons and djinns and an enchanted island that was never in the same place twice.

And of course there are illustrations from the books for which he’s probably best known, the Tim and Ginger series, which he wrote as well as illustrated — he did 17 books as author and illustrator — but the exhibition isn’t just about the children’s books.

That’s the point.

Actually, I feel rather embarrassed now that I only ever associated Edward Ardizzone with children’s stories — which Puffin, to their infinite credit, are still producing (check out The Little Girl and the Tiny Doll). It’s like going on about how brilliant T.S. Eliot is when all you’ve read is Old Possum’s Book of Practical Cats.

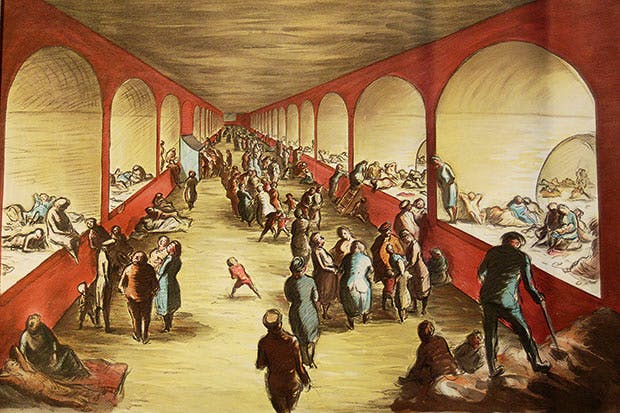

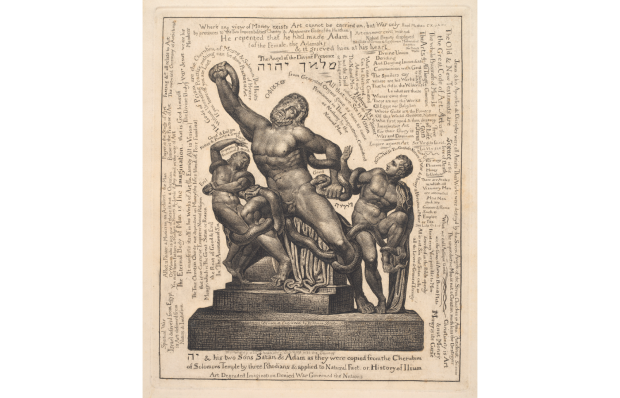

He was a serious artist, much admired by Kenneth Clark, often compared to Daumier for his thick outlines and heavy shadows, and as an official war artist he was probably the most effective in capturing the human aspect of the war. He was quite extraordinarily prolific — one of the good things about being financially hard-pressed quite a lot of the time — and his oeuvre, represented here in more than 100 pieces, encompasses his advertising and commercial work (there’s a charming poster for Guinness showing a cheery workman carrying not only a piano but also a piano player), his many illustrations for adult books, his pictures of London pub and street scenes and his war paintings.

He was never — except in his murals for a church in Faversham — overtly religious, though his own Catholic sensibility, a warm humanity, infused everything he did. As an artist he was a lover of mankind, a storyteller, in the way Dickens was; his pictures of tarts, drunks, chipper working-class girls, many of them seen close by his home in Maida Vale, were affectionate, unjudgmental — and reflected the political preoccupations of the International Artists’ Association to which he belonged, which emphasised the importance of social realism. Indeed, for a man of his kindliness, it’s notable that his least sympathetic figures are rich men. You can see as much in his collaborations with Graham Greene in books such as The Little Horse Bus where the plutocrats are baddies. (Interestingly, those books aren’t really successful: Greene was too arch, too knowing.)

He seems an improbable choice of official war artist, given that others included Graham Sutherland, John Piper and Henry Moore, but he was recommended by Kenneth Clark who wanted an artist ‘who would show the earthy part …what military life was really like’. And while he of all artists found it most difficult to show man’s hateful aspect — as with Dickens, ‘cheerfulness will keep breaking out’ — his sympathetic approach and eye for the absurd was entirely apt.

One image, ‘On the Road to Tripoli: Cup of Tea for the Burial Party’, shows squaddies calmly drinking mugs of tea in front of three open graves, which, you feel, was how it was. There are uncharacteristic exceptions here, though, including the sparse, bleak ‘A Battery Position in an Orchard of Young Fruit Trees in the Snow’, in ink and wash.

Paring the material down to the selection here must have been a formidable undertaking for the curators, Alan Powers (who has written an admirable monograph to accompany the exhibition: Edward Ardizzone, Artist and Illustrator, Lund Humphries, £40) and Olivia Ahmad. In fact, the exhibition, over three rooms, is probably the right size, given that a number of the exhibits are small-scale, to be pored over. For good measure, there’s a bookshelf that stood in his sitting room, and a little theatre that he made for domestic theatricals. It’s a gem of an exhibition; for fans of Ardizzone, and we are legion, it’s a must.

There’s also a small, charming display of his work at Chris Beetles Gallery in St James’s, The Human Comedy, which includes some lovely pub scenes (‘Barmaids Old & New’), pictures from one of his collaborations with Robert Graves, and some enchanting illustrations for Eleanor Farjeon’s Italian Peepshow. Honestly, there are times when he resembles no one so much as Watteau — a world in which sin and death never enter. And from the end of the month the show will be incorporated into the gallery’s ever-brilliant annual exhibition, The Illustrators. It’s a delight.

The post Serious concerns appeared first on The Spectator.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in