Picking a day at random, ‘an unremarkable Saturday in America’, the Guardian journalist Gary Younge identified ten children and teenagers throughout the United States who were shot dead on 23 November 2013. Whichever day he chose, he knew it would be typical. Determined to investigate each of these deaths, none of which bore much — or any — press coverage even locally, Younge would pore over the internet, visit grim parts of cities far from his Chicago home, locate as many relatives, friends and witnesses as he could and speak to them. His book, Another Day in the Death of America, is as one would imagine it: sad and bleak, an altogether terrible tale. Hopeless, too: no one, certainly not Younge, is under any illusion that this story will get better. While Britons spent the summer of 2016 debating Brexit, Americans were confronted with daily shooting deaths on the usual outlandish scale, made more so by the mass killing in Orlando and the handful of police-on-civilian fatalities, followed by civilian-on-police murders, that drew all the headlines but are not actually the types of crimes Younge is featuring in his book.

In that book, where each chapter is headed by a person’s name, age, city and time of shooting, there risks being little narrative suspense. How does such a book of ten stories, painfully alike, unfold? Could you just read one or two and get the point? And so Younge has made his book a masterclass in journalism. Unobtrusively, he explains how he follows leads, gets a few breaks, meets dead ends and readjusts his plan in each fatal neighbourhood. He reviews press coverage in America on gun violence, and considers the professional roles of journalists and publishers (‘journalism is not social work’), and the limits of covering people who are not as white, educated and relatively well-off as reporters tend to be. Younge himself is a black Englishman born into a working-poor immigrant family, a background that might seem to give him entrée among his subjects (seven of the ten dead children are black), except that to do his job he has to open his mouth. In Dallas, the funeral director for Samuel Brightmon (age 16) ‘could not understand a word I had said’. In San Jose, trying unsuccessfully to interview people in a park where a Latino 18-year-old, Pedro Cortez, was shot, his English accent is ‘one variable too many’ for the kinds of questions he is asking.

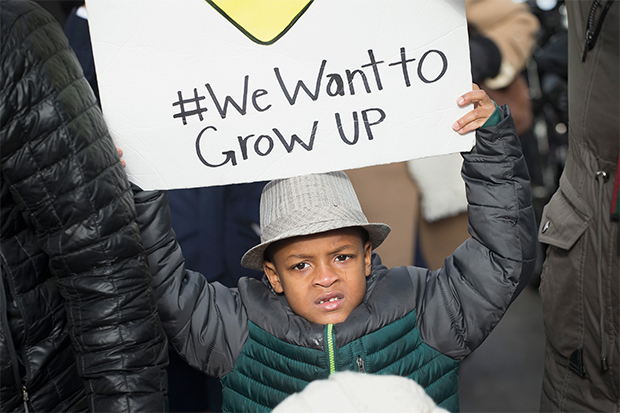

Since everyone will agree these stories are wrenching and that, whatever their behaviours, none of these victims ‘should’ have been shot (with one powerful exception, their criminality, if any, is minor), most readers will have to dig deep to find their disputes and Americans especially will peer into Younge’s motives. He’s black, foreign, reporting for a liberal newspaper — surely he’s anti-gun, wary of law enforcement, an apologist for urban pathologies that ignore the primacy of ‘personal responsibility’, and so on. Indeed, he may be those things — none is bad! — but all of it is muted before the journalistic imperative to describe the daily hideous consequences of American gun culture, the thing ‘most foreigners find hardest to understand’. But most Americans don’t understand it, either, because in our segregated country people of different ethnic and racial backgrounds don’t live and struggle in the same communities in the same ways. Even though white gun culture is the most significant component of American violence, only one of these ten boys — they are all male — is white, from rural Michigan where, like all hunting states, guns proliferate, resulting in many homicides including what seems, in the case of Tyler Dunn (age 11), an accident at the hands of another kid. The 1950s-style full-page illustration of a prosperous white American family strangely chosen for the cover of Younge’s book represents instead the more fortunate people who, because of US structural inequality, are ‘better equipped to be safe’ in a gun country.

All of it is perfect madness. In his afterword, Younge says that reporting and writing the book ‘made me want to scream’. His success is that for the hours you are absorbed in it, you start to see how life on the streets can be normal; that it might actually be — gulp — a blessing for the only real gangbanger among the deceased, Tyshon Anderson of Chicago (age 18), to have been brought down. ‘I’m just glad it’s over,’ says a family friend who loved Tyshon, ‘because now every day I have to live is a day when they’re not going to kill him. It’s a day when he’s not going to die.’ In other words, it’s every day since 23 November 2013. But for many families, that day comes tomorrow.

The post In a gun country appeared first on The Spectator.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in