‘Here is a story from the winter days of the end of 1959 and the beginning of 1960,’ announces the opening sentence of Amos Oz’s challenging, complex and strangely compelling new novel. The story itself is easily summarised. At its centre is Shmuel Ash, a rather woebegone young man who abandons his university studies in Jerusalem when his girlfriend leaves him and his father withdraws his financial support. At a loss for what to do next, Shmuel takes up a job which requires him to live in a rickety, isolated house surrounded by an air of almost hermetic secrecy; and to provide tea, company and, most crucially, conversation for an old invalid named Gershom Wald, whose life is almost entirely confined to his study, and to vociferous telephone exchanges with old sparring partners and friends. The other inhabitant of the house is an enigmatic and very aloof woman named Atalia, who treats Shmuel with abrupt, but to him highly seductive brusqueness. Such plot as there is involves gradually unfolding revelations about the house’s inhabitants, and the halting progress of the relationship between Atalia and Shmuel.

But the plot here is not the point. Judas belongs to a genre not much practiced in English fiction — the novel of ideas, in the lineage of Dostoevsky or Tolstoy or Thomas Mann; and its drama inheres not so much in realist narrative or action, as in its suggestive Jerusalem setting — cold, rainy, poor and, in that in-between period, featuring both abandoned Arab villages and nostalgically European cafés — and in the intensely philosophical conversations between the novel’s main protagonists. The extended debate conducted in Gershom Wald’s dusky study revolves around quandaries which originated in Jerusalem 2,000 years ago, but which for the inhabitants of that symbolically laden city continue to have existential relevance: the identity of Jesus; the identity of Judas; the mutual prejudices and fears between Christians and Jews; the ease with which the persecuted turn into persecutors (with both positions being potentially occupied by Christians, Jews and Arabs); the fascinating history of Jewish writings on Jesus; and, informed by and informing all of these, the identity of modern Israel.

Perhaps as part of the novel’s intention to counter facile oppositions or stereotypes, the interlocutors in these complex, dialectical dialogues are described in curiously, and sometimes disturbingly, ambiguous terms. Shmuel Ash is asthmatic, clumsy, easily given to tears, chronically compassionate and timidly indecisive — a cross between a gentle Jewish schlemiel and the saintly protagonist of Dostoevsky’s The Idiot. His master’s thesis, on ‘The Jewish Views of Jesus’, is a defense of Jesus’ gospel of universal love, if not of his divinity; and at the novel’s outset, he belongs to the Socialist Renewal Group, with its promise of revolutionary utopia. His philosophical antagonist, and to some extent mentor, comes from Latvia (with the suggestion, never specified, that he might have a connection to the Holocaust), and physically he resembles the awful images of anti-Semitic caricatures and fears: hunchbacked, crippled and suffering from a ‘degenerative disease’. At the same time, Wald is an intellectually and ethically commanding figure — a transplanted Enlightenment humanist in the rich Central European vein: erudite, ironic, argumentative and fiercely sceptical of all utopian faiths. ‘If I had to choose a thousand times between our age-old sufferings and their salvation and redemption,’ he says, making fun of Shmuel’s allegiance to Lenin and Jesus, ‘I’d rather they left us all the pain and sorrow and kept their world-reform for themselves, seeing that it always involves slaughter, crusades or jihad, or Gulag, or the wars of Gog and Demagogue.’

At the novel’s philosophical heart, however, is the vexed question of Judas, and the paradoxical relationship between what might be called extreme idealism and treason. In Shmuel’s esoteric view, Judas — who in the Christian imagination is often seen as the archetypal Jew and archetypal traitor — was actually the truest of believers, the apostle who was most fully convinced of Jesus’ divinity and who worked to bring about the crucifixion so as to demonstrate it to the world. (This seemingly wild interpretation apparently echoes a second-century Gnostic ‘Gospel of Judas’.) The contemporary equivalent of Judas in the novel is Atalia’s father, Shealtiel Abravanel, who believed that peaceful co-existence between Arabs and Jews could be brought about, if only Jews refrained from establishing a state and exercising power, and who was expelled from a group of Israel’s founders for his views.

Gershom Wald counters the seductive high-mindedness of such visions with a disabused and melancholy realism. In the novel’s scheme, neither Judas nor Abravanel are seen as actual traitors; but there is a suggestion of an implicit, paradoxical relationship between what might be called extreme idealism and a kind of disavowal, or even a betrayal, of necessary human truths. At the human heart of Judas is the revelation that Wald’s only son — who was also Atalia’s husband — was brutally killed in a skirmish between Israeli and Arab fighters; and the father’s anguished sense of loss lends a genuine poignancy to the novel, and emotional heft to its more abstract debates. His aversion to explanatory systems of belief — whether theological or ideological — comes from his understanding that the conflicts and contradictions of human nature cannot be extirpated or cured, and from his acceptance of its tragic limits. Jesus, after all, did not step down from the cross; and without a state, Wald believes, Jews might not have survived in the Middle East. The costs of having power, he implies, are enormous; but the costs of powerlessness may be even greater.

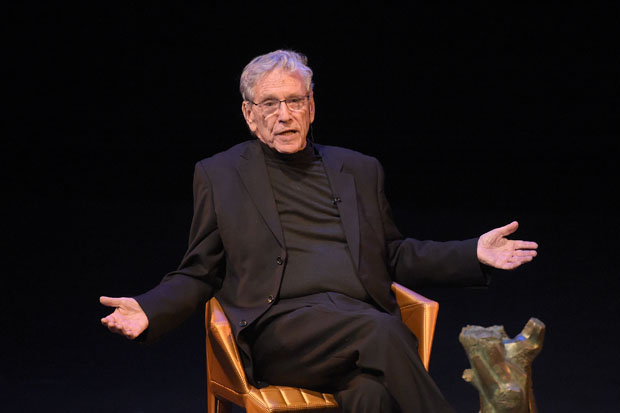

Judas is not a wholly successful novel. The scenarios which move the narrative forward too often seem to serve as a rather rote pretext for the novel’s real concerns. The character of Atalia, with her icy detachment throughout much of the novel, and her rather perverse seduction of Shmuel towards its end, is oddly unconvincing. But the ideas at the novel’s centre have great vitality and force. The philosophical passages bristle with linguistic energy, scriptural references and dense detail, vividly conveyed in Nicholas de Lange’s translation. The dilemmas with which the protagonists passionately struggle remain inevitably unresolved; but in trying to get to their very root, Oz illuminates issues critical to the identity of contemporary Israel — and indeed, much of the contemporary world. Both the ambivalence and the passion pervading this demanding and uncompromisingly serious novel, are, one suspects, Amos Oz’s own.

The post Thinking of Israel appeared first on The Spectator.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in