Art Spiegelman, the American cartoonist behind Maus, the celebrated Holocaust cartoon, dreamt up a good definition of graphic novels: comics you need a bookmark for. This jolly show about the British graphic novel takes an even broader approach.

It begins with Hogarth’s 1731 series, ‘A Harlot’s Progress’, the tale of an ingénue in London who becomes a prostitute and dies of syphilis. You’d need an awfully big bookmark for the six original paintings in Hogarth’s series. But the point is well made — the idea of telling stories through a series of pictures has been around for a long time in Britain.

Perhaps that’s why we’ve often denigrated cartoons and comics — we take them for granted. The late, great Ronald Searle was treated far more seriously in France than he was here. Incidentally, there’s a terrific Searle graphic novella in the show. ‘Capsulysses’, from Punch in 1955, tells the story of Caps, chief of Ithaca, returning home through the Med, after beating the Axis powers in the second world war. The Odyssey rip-off is drawn with all Searle’s joyful brio and anarchic line.

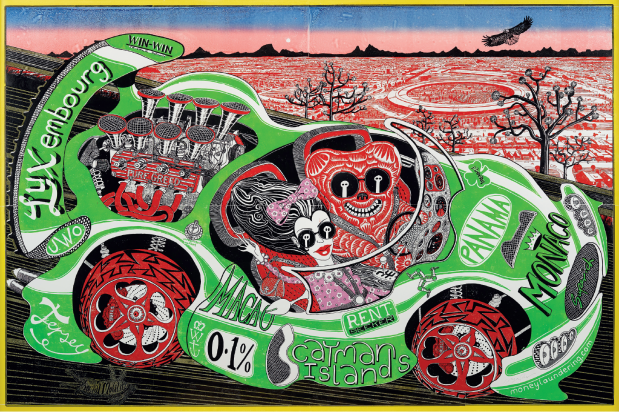

It’s wrong to demote cartoonists and graphic novelists like this, but it has a beneficial effect: these cartoonist-writers take themselves less seriously than straight writers or straight artists, and they’re outside the establishment. It means they’re that much funnier and more satirical — like the cartoons of Private Eye stretched into a novel.

Take the master of the graphic novel, Posy Simmonds, whose works figure prominently at the Cartoon Museum, celebrating its 10th birthday this year. Her books are wickedly funny, and skewer certain types —particularly academics, journalists and writers — better than any conventional novel. I was glad to find Simmonds’s supreme works, Gemma Bovery, 1999, and Tamara Drewe, 2007, in the London Library. But, actually, they do more than a novel can.

With Tamara Drewe, I found myself reading the captions, looking at the cartoon, reading the speech bubbles and then going back to look at the little cartoon details — the crumpled bag of Riso Scotti used for the risotto at Stonefield, the classic writers’ retreat; the teen magazines read by the girls in the local bus shelter (‘Goss — Celebrity snogathon!… Chico’s packet’).

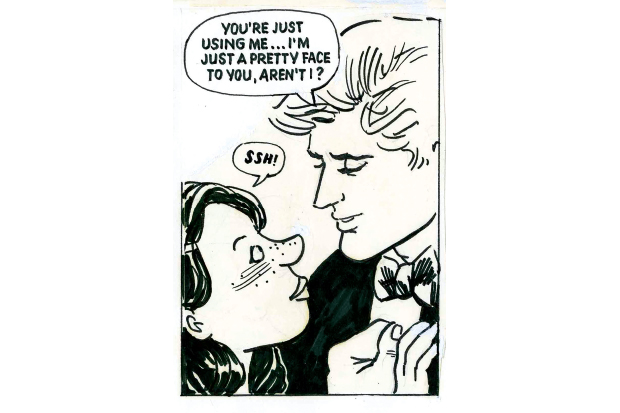

The exhibition also features panels from Simmonds’s 1981 graphic novel True Love, which cleverly mocks the conventions of teen romance cartoons. Some say that True Love was the first British graphic novel. But that definition of the graphic novel is so slippery that it’s impossible to nail down a precise, unarguable original.

You wouldn’t call H.M. Bateman a graphic novelist but what a delight to see his ‘Getting a Document Stamped at Somerset House’ (1923) — the pitch-perfect 1920s testament to the rage we feel today at being put on hold during a call to a Bangalore call centre.

Tatler — which printed that Bateman cartoon — collected his strips together in booklets. That doesn’t make them graphic novels, but still, you can see the growing trend towards the fully self-aware graphic novel through the course of the 20th century.

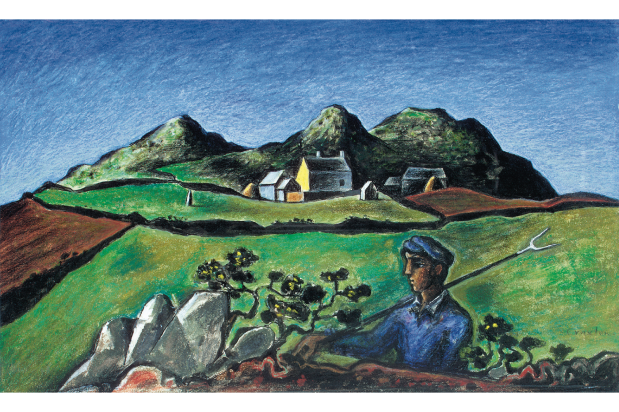

In the late Seventies and early Eighties, the British graphic novel really took off around the world, particularly in the works of Bryan Talbot. His science-fiction work The Adventures of Luther Arkwright (1978) also vies for that nebulous slot as Britain’s first graphic novel. In 2012, Dotter of Her Father’s Eyes, by Talbot and his wife Mary — the story of James Joyce’s daughter, Lucia — won the Costa biography prize; a welcome sign of how seriously graphic books are now taken.

That Eighties graphic-novel boom was rooted in science fiction and a dark, dystopian world, as captured in V for Vendetta (1988), by Alan Moore and David Lloyd, the post-apocalyptic novel that spawned V, the anarchist in a Guy Fawkes mask adopted by protesters across the world.

Dark non-fiction stories have increasingly found their way into graphic novels, such as Will Kevans’s My Life in Pieces: The Falklands War (2014) and Becoming Unbecoming (2015), the story of the Yorkshire Ripper. Only a few years ago, the idea of putting the Yorkshire Ripper in a cartoon might have seemed somehow shocking — because cartoons are really for children, aren’t they? Not any more.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in