‘My daughter’s moving to Saffron Walden, away from all this,’ said the railway man at Stratford station, gesturing at the tower blocks overlooking the platform. ‘It’s like going back to the 1970s and ’80s.’

Further back, in the case of Saffron Walden’s Fry Art Gallery. Purpose-built by a Victorian banker to house his collection, this gem of a gallery has since been devoted to collecting and showing artists who have lived and worked in north-west Essex, beginning with the group that congregated around Edward Bawden and Eric Ravilious in Great Bardfield from the 1930s. Half the gallery’s miniature enfilade is currently hung with their work, while the other half has been given over to a display of British neo-romantics including loans from the Ingram Collection.

The Englishness of Bawden, Ravilious and co. is too obvious to require elaboration, but it’s harder to get a handle on the neo-romantic movement that sprang up on this island in the shadow of the second world war. For the purposes of this show it’s described as British to accommodate ‘The Two Roberts’, Colquhoun and MacBryde, who left their native Scotland in 1941 to join the two Johns, Minton and Craxton, Keith Vaughan and Michael Ayrton on the London art scene that revolved around the watering holes of Soho and Fitzrovia.

Glasgow-trained and working class, the Two Roberts owe their presence in the Fry’s collection to their notoriously rackety three-year stay in the early 1950s in a borrowed cottage near Great Dunmow, most of whose contents they allegedly smashed or sold. Unlike the English members of the group, these Ayrshire-born artists did not worship the ground Samuel Palmer walked on or adopt Graham Sutherland’s black shadows and twisted tree roots. They were more at ease with French modernism than their English friends, for whom war offered the chance to escape from Roger Fry’s ‘significant form’ into a lyricism expressed in figurative works on paper. It allowed a naturally gifted draughtsman like Minton to shine in watercolour paintings such as ‘The Hop Pickers’ (1945), combining detail with luminous simplicity (see below), and Vaughan to piece together wartime sketches made in the Non-Combatant Corps into dreamlike Arcadian compositions. His ‘Garden at Ashton Gifford’ (1942) is a world away from the prosaic paintings of land girls commissioned by the War Artists’ Advisory Committee.

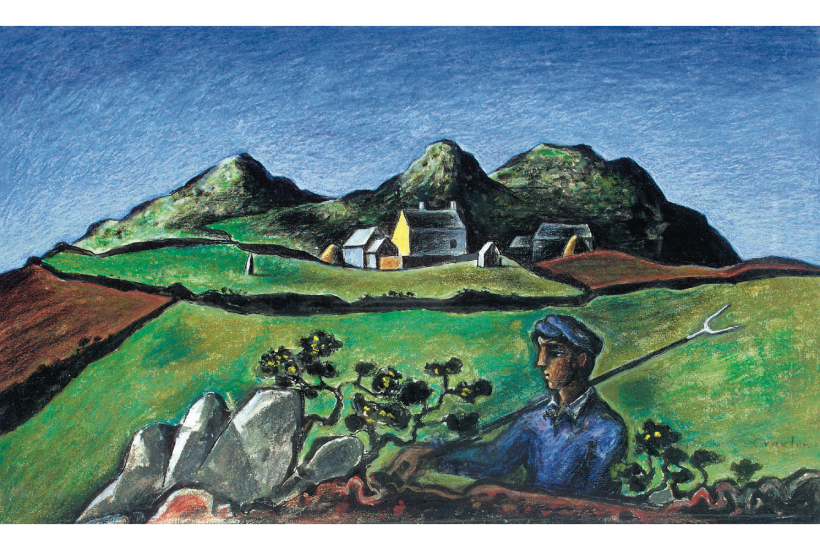

While rejecting Fry’s boasted indifference to whether a picture’s subject was ‘Christ or a saucepan’, the neo-romantics didn’t go so far as to share Palmer’s religious faith in Nature as ‘the veil of Heaven… and proscenium of eternity’. For them, as for their patrons, the pastoral mode was an escape from the grimness of everyday wartime reality. ‘Moons are in!’ ‘Half-moons are really selling this year!’ joked Minton, in defiance of the fact that wartime moons benefitted German bombers. Only Michael Ayrton conveys a sense of foreboding in paintings like ‘Loneliness’ (1940) and ‘Winter Drought’ (1944); John Craxton, the baby of the group, is incorrigibly upbeat. With its impossibly blue sky, his ‘Reaper in a Welsh Landscape’ (1945) anticipates the vibrant landscapes he would paint in Crete, though the shadows – a hangover from his mentor Sutherland – remain black.

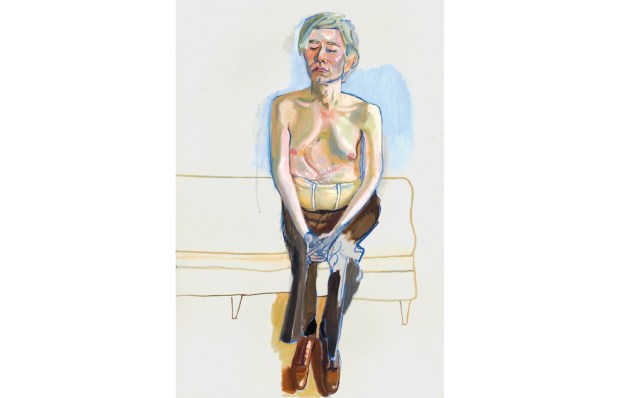

By 1950 the wartime window was closing on what William Scott, a lapsed neo-romantic, later dismissed as ‘the English watercolour nationalist romantic patriotic isolationist self-preservation movement’. In a post-war world the pathetic fallacy looked pathetic; the Kitchen Sink School flushed it down the realist plug. Minton’s last Lefevre Gallery exhibition in 1956, the year the Kitchen Sink painters represented Britain at the Venice Biennale, was panned by critics impatient of ‘the touching and melancholy impermanence of all physical beauty’ he still sought to enshrine in his art. Critics were brutal, too, about the horses and masked figures in Colquhoun’s 1951 Lefevre exhibition, despite their modernism; like Minton and the other Robert, he sought solace in drink. In the face of pop art even Vaughan – whose ‘Troys Farm’ (1960-72), with its geometric patchwork of fields, comes within a squeak of abstraction – began to ‘understand how the stranded dinosaurs felt when the hard terrain… suddenly started to get swampy under their feet’.

Minton took an overdose 1957; Vaughan chose the same way out 20 years later. MacBryde fell under a car in Dublin while drunk in 1966, four years after Colquhoun’s death in his arms from a heart attack. In the final issue of Horizon magazine in 1950 a reproduction of Francis Bacon’s ‘Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion’ (1944) was accompanied by this epitaph by Cyril Connolly: ‘It is closing time in the gardens of the West and from now on an artist will be judged only by the resonance of his solitude or the quality of his despair’. The neo-romantics’ despair was of the wrong quality – polite and private – but through the gate they held open the gardens can still be glimpsed.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in