How clean are you? I ask not as a mother confessor. I’m not interested in the state of your soul. What I want to know is: how clean is your sock drawer? Your fridge? Your gut?

These are the pressing questions of the new cult of clean. Its apostles urge us to divest ourselves of worldly possessions, to renounce ‘dirty’ food and alcohol and to dress in monkish grey or bleached white. Our sins are these: we have bought too much tat, eaten to filthy excess and stuffed our wardrobes with cheap, disposable rubbish.

The clean cultist says no more. Everything must go. The most high and holy of the clean cultists is Marie Kondo, Japanese author of The Life-changing Magic of Tidying. She asks us to take everything we own — from family heirloom to gas bill — hold it in our hands and demand of it: does it ‘spark joy’? If not, throw it out. Her tidying regimes and devoted following have seen her listed in Time magazine’s 100 Most Influential People in the World. Her name has become a verb: ‘to Kondo’ — to have an almighty clearout.

Spreading the gospel from the West is the Californian clutter refusenik Bea Johnson. Her book Zero Waste Home preaches the five Rs: ‘Refuse, reduce, reuse, recycle, rot.’ We are told to chuck or give away our books, our children’s toys — even our engagement rings. She cleans everything in the house with a dilute solution of white vinegar.

Completing the clean-and-clear trinity is the trend forecaster James Wallman. Clean cultists have read his manifesto Stuffocation: Living More with Less via iPad, learned its lessons, and consigned it to the desktop trashcan. Clean cultists don’t do physical books, CDs or DVDs.

They nodded when the handbag designer Orla Kiely announced: ‘The world is full of stuff, and it is too much.’ They cheered when Steve Howard, chief sustainability officer of Ikea — the shop that sells more than six million Billy bookcases a year to house all the books we’re not supposed to be buying — said that in the West we have ‘hit peak stuff. We talk about peak oil. I’d say we’ve hit peak red meat, peak sugar, peak stuff, peak home furnishings.’

The clean cultists have given up red meat, sugar, dairy and gluten. Nothing processed passes their lips. They eat clean, snack lean and drink green juices for breakfast. They strain their own almond milk and ‘activate’ their sunflower seeds.

They cook from books with titles like Good + Simple, I Quit Sugar, and Cook, Nourish, Glow, Oh She Glows, Get The Glow, and Ready, Steady, Glow. Glowing is important to the clean cultist: inside and out. They are converts to the gut-scouring properties of fermented foods. Jars of fizzing white cabbage sauerkraut and pickled kimchi sit next to the Vitamix juicer on the kitchen work surface. They have read and digested the lessons in German microbiologist Julia Enders’ Gut: The Inside Story of Our Body’s Most Underrated Organ. They do not drink grubby alcohol.

Fashion, too, has discovered a clean streak. The editors on the front row wear head-to-toe grey. Grazia magazine has christened it ‘the groutfit’. I recently passed designer Stella McCartney on the platform at Paddington station, and she was wearing a grey cashmere coat, a grey cashmere pullover and grey cashmere jogging bottoms, cropped at the ankle. She looked divine, if grey.

At the beginning of this year, Mark Zuckerberg, founder of Facebook, posted a photograph of his back-to-work wardrobe after two months’ paternity leave with the caption ‘What shall I wear?’ The rail held nine identical grey T-shirts and seven darker grey hooded sweatshirts, all fresh from the washing machine.

The photograph was liked more than a million times and more than 74,000 comments were posted under it. Zuckerberg has told Facebook users: ‘I really want to clear my life to make it so that I have to make as few decisions as possible about anything, except how to best serve this community.’ Marie Kondo wears white blouses; Bea Johnson wears black T-shirts.

Through my teens and early twenties every woman aspired to long, boho, artfully unwashed and dishevelled hair — think Sienna Miller in her Jude Law heyday — now it’s a short, neat, wash-and-go bob.

The fashion girls would no more carry a slouchy designer handbag, logoed, named after a celebrity and hung about with a clutter of Prada robot charms, than they would eat a Mars bar. Instead they carry compact rucksacks from the Scandinavian brands Sanqist and Fjallraven Kanken.

Scandinavia is mecca. The clean cultist buys its bags, watches its TV shows, and imports its Pilen bikes. A bike is preferred to a dirty, petrol-belching car.

The dream holiday is no longer to Ayia Napa (noisy), India (dirty) or Thailand (too colourful) but Stockholm, Oslo, Bergen and the fjords. The clean cultist aspires to the austerely empty (grey) studio apartment in which Eddie Redmayne and Alicia Vikander live in The Danish Girl, each room like a Hammershoi painting. They fantasise about giving away all their remaining possessions and moving to Copenhagen or Aarhus.

Some of the ideals of the clean cultist are understandable. In large part, the movement is born out of a nervous reaction to too much cheap junk food and too much stuff. Marie Kondo describes her own teenage breakdown: coming home from school one day and wanting to throw away everything in the family home.

After decades of Primark dresses, worn to one party and then chucked, of iPods which were replaced by iPod Minis then iPod Nanos then iPod Shuffles then iPhone after iPhone, and of free plastic sunglasses with your monthly fashion mag — all piling up in landfill — it is reasonable to turn around and adopt Bea Johnson’s maxim: ‘I refuse.’

What’s more, for the generation who cannot get on the housing ladder, there simply isn’t space for clutter. Even if you have successfully moved out of the family home (and many haven’t: the last census found that 26 per cent of adults aged between 20 and 34 were still living with their parents, up from 21 per cent in 1996), you are probably living in a cramped rented flat with barely a shelf of storage space. Faced with living in a broom cupboard, it may seem better to dress up a lack of possessions as a lifestyle choice, rather than accept that it is a dreary consequence of being a part of Generation Rent.

There may also be a religious element to this asceticism, or rather, a compensation for a lack of religion. If you don’t go to church on a Sunday or synagogue on a Saturday, if you never say a prayer or a confess your sins, if you aren’t saving yourself for marriage, you may find yourself missing the pleasing discipline of restraint. Instead of religious self-denial, you can do retail self-denial.

I ought to be in sympathy with the clean cultists. I am teetotal and I file my paperclips in little Perspex boxes. Marie Kondo would thrill to my sock drawer. But something about this back-scouring cleanliness, taken to its extreme, troubles me.

However much the clean cultist’s skin may ‘glow’, the purity is only skin-deep. The cult of clean isn’t about shrugging off material things to create more time, space and energy to volunteer for a charity or help at a food bank, or even just to spend more time with friends and family. The modern cult of ‘wellness’ — wellness, like cleanliness, being next to godliness — has nothing to do with the old-fashioned virtues of goodness or kindness. You can be as venal, self-centred, smug, hypocritical and preaching as you like, so long as your outward image is cleaner than clean.

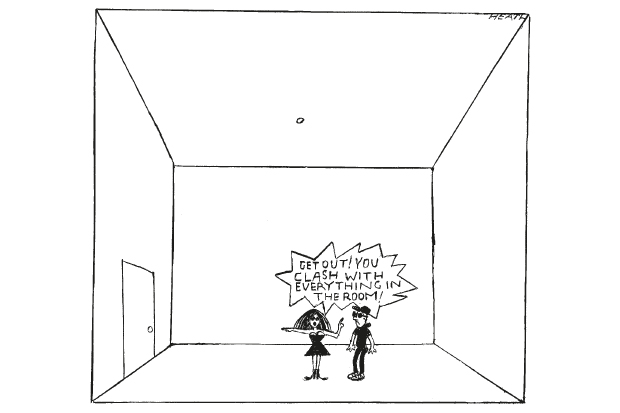

It feeds, too, into the Stepford Student syndrome, identified in this magazine by Brendan O’Neill. This is the tendency to approve only one point of view and to ‘no-platform’ any speaker who dissents. Anyone not on message about trans issues, the migrant crisis or abortion will find themselves summarily ‘Kondoed’ from the campus. What is a ‘safe space’ if not somewhere white, tidy, clean and antiseptic, with nothing on the walls to offend a delicate sensibility?

Today’s students are much more fastidious than they were even when I went up to university ten years ago. Then, we arrived with cheese toastie-makers. Last year, the Which? consumer guide reported a 272 per cent rise in sales of the Nutribullet — an £80 juicer — in August before the start of university term. Freshers are downing not Jaegerbombs but chia seed smoothies.

My old student newspaper, Varsity, runs recipes for ‘incredibly healthy vegan sweet-potato ice cream’ blended in a Nutribullet. It’s enough to make you nostalgic for cheesy chips from a van.

An obsession with aesthetic and nutritional purity gives the clean cultist a misplaced sense of intellectual purity. Having become masters of their own sock drawers, they believe everything else — a dissenting voice, a statue of a college benefactor, a protest group — can be tidied away. Only their view is acceptable. Any person who challenges the tasteful grey orthodoxy is just too messy.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in