In a remote fishing village a lone figure confronts an unexplained death, standing tormented but unbroken against fate, the community and the elements of sea and wind that surge through every note of the score. No, not Peter Grimes: this is Vaughan Williams’s 1932 operatic setting of Synge’s Riders to the Sea. But Vaughan Williams’s operas are undramatic, runs the received wisdom. There were no great British operas between Purcell’s Dido and Aeneas and the premiere of Grimes in 1945, we’re repeatedly told.

This student production of Riders to the Sea didn’t just refute those assumptions: it threw them into a riptide and watched them being dragged under and swept away. From Vaughan Williams’s opening bars, the gale starts to rise and the green-grey swell begins to gather its murderous strength. Strings foam and swirl, oboes keen: economically, powerfully and without a trace of sentimentality, Vaughan Williams unfolds a 40-minute anatomy of grief. In the foreground, meanwhile, two sisters go about their daily tasks and fret over how to conceal from their ageing mother the scraps of damp clothing that seem to prove that yet another of her sons has been lost to the sea.

Birmingham Conservatoire’s staff director Michael Barry has been achieving striking results with limited means for some years now, largely untroubled by attention from national critics, and his production made its points simply. The set provided the rudiments of an Irish cottage, with the sky above it streaked by an angry beam of light. The two sisters (Aimée Fisk and Hannah McDonald) both sounded and looked like siblings, their voices determinedly bright and firm, only briefly fading off into tenderness or hardening with pain — vocal acting that was of a piece with Barry’s naturalistic direction. But the drama pivots on their mother Maurya, sung by Samantha Oxborough: an artist in her twenties who managed not only to embody a woman with a lifetime’s harsh experience, but whose voice had a core of savage intensity and a glow that in her defiant monologues convinced you that you were hearing a masterpiece.

It was the centrepiece of a triple bill, alongside Holst’s Savitri — minimally staged, with delicate touches of Indian choreography, and Cecily Redman as a sweet-toned heroine — and Ravel’s L’Enfant et les sortilèges, updated by Barry to a mid-20th century school hall, the idea being that the whole thing is a primary school play. With the entire cast on stage and in character as fidgeting, paper-dart-throwing children throughout, it was vivid, engaging and very much in the child’s-eye spirit of the thing — didn’t Colette describe her libretto as a ‘divertissement pour ma fille’? The student orchestra under Fraser Goulding sounded like they were having the time of their lives, the only real problem being that the gradual emotional awakening of Chloë Pardoe’s spiky-haired, crystal-voiced Child — the heart of the whole piece — vanished somewhere under the mass choreography.

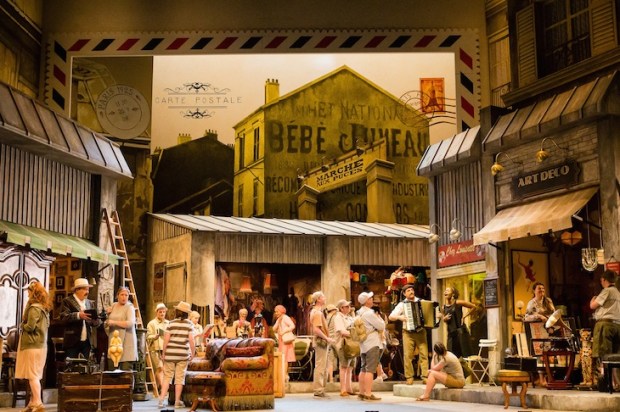

The Royal Academy of Music’s production of Rimsky-Korsakov’s May Night was an altogether more straightforward proposition. The opera itself is a delight: a romantic folk-comedy after Gogol, laced with gentle mysticism and luminously scored. Rimsky’s a natural storyteller. Done more or less straight with a light enough touch, his comic operas work every time — as ENO discovered with May Night’s sister-piece Christmas Eve back in the Powerhouse era.

Most of the challenges in Christopher Cowell’s production derived from the venue: Ambika P3, a cavernous industrial bunker off Marylebone Road. Evoking rural magic was clearly a non-starter, so Cowell moved the action up to the Soviet era (complete with Heroic Tractor Driver dungarees and sacks of potatoes, the USSR being the genocidal tyranny that we’re all allowed to find enjoyably kitsch) and set it inside the village’s newly built distillery. There were some entertainingly surreal touches — the chorus of rusalki, the spirits of young girls who drowned themselves for love, appeared as Tim Burton-ish corpse brides with dayglo orange hair.

That done, it zipped along joyously: peasant choruses jogging on and off stage in Keystone Kops synch, and singing with a ripeness that would have done the Mariinsky proud. As the young lovers Levko and Ganna, Oliver Johnston and Laura Zigmantaite had considerable charm, Johnston’s tenor taking on a ringing Slavic edge — you just wished Cowell had let them get a little closer to each other. Alys Roberts as the drowned girl Pannochka crested her vocal climaxes with yearning intensity, and down in the pit Gareth Hancock’s orchestra sent harps swirling and clarinets bubbling in all directions. The final scene, as Rimsky ditches Gogol and transforms his village romance into a pagan spring ritual of death and rebirth, with shouts of ‘Slava!’ filling the air, struck home impressively — making you wonder why we’re relying on students to see this opera. Forget received wisdom: the kids have got it right.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in