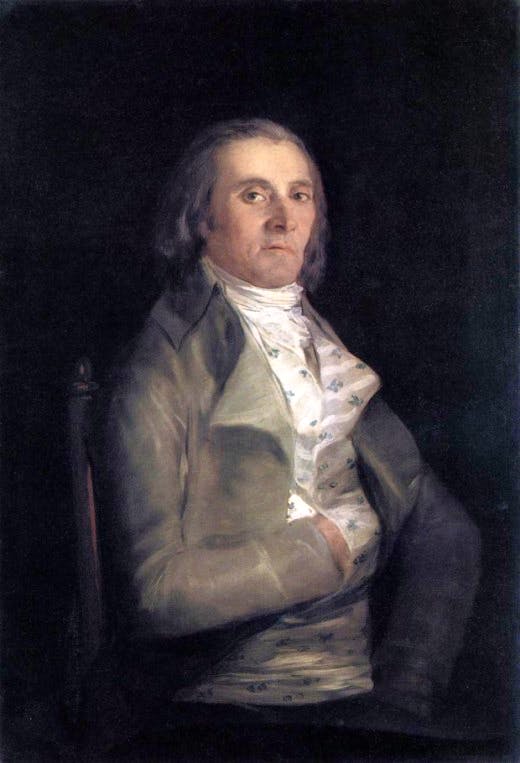

Sometimes, contrary to a widespread suspicion, critics do get it right. On 17 August, 1798 an anonymous contributor to the Diario de Madrid, reviewing an exhibition at the Royal Spanish Academy, noted that Goya’s portrait of Don Andrés del Peral was so good — in its draughtsmanship, its freedom of brushwork, its light and shade — that all on its own it was enough to bring credit to the epoch and nation in which it was created. He (or she) was absolutely correct.

Goya’s portrait of Don Andrés del Peral

The same could be said of many of the exhibits in Goya: The Portraits at the National Gallery. The people in these pictures rise up, as Vincent van Gogh hoped his own portraits would do in the future, like apparitions. There they are in front of you, these people who lived two centuries ago, with all their poignancy, absurdity, passion and energy.

Goya’s ‘Charles III in Hunting Dress’

It is because Francisco de Goya y Lucientes (1746–1828) made them look so alive that we are interested in the time and place in which they lived. Otherwise, who except specialists in Hispanic history would pay much attention to late 18th- and early 19th-century Spain? But as it is, we want to learn about these fascinating people that Goya shows us (and by reading the excellent catalogue, by the curator Xavier Bray, we can).

This is not to say that, magnificent as the exhibition is as a whole, it is entirely made up of masterpieces. Goya was a slow starter. Although he had formal training, he was essentially self-taught (as he noted).

Goya’s ‘The Count of Floridablanca’ (1783)

Some of his earlier efforts have a stiff naiveté that is close to folk art. The main figure in the ‘The Count of Floridablanca’ (1783) (above) is wooden and doll-like and yet the painting as a whole is oddly memorable. Goya himself — short, subservient and sturdy, presenting a painting to his patron and simultaneously pushing himself into the picture — is a more lively presence than the noble subject.

Even while he was following the protocols of aristocratic portraiture, Goya just couldn’t stop himself noticing — and depicting — all sorts of extraneous and revealing sights. Cats, their eyes bulging with ferocious greed, wait to pounce on the pet bird held on a string by the dandified toddler, ‘Manuel Osorio Manrique de Zuñiga’ (1788). There are such subversive undertones and notes of sardonic comedy to many of his pictures.

Goya’s ‘Manuel Osorio Manrique de Zuñiga’ (1788)

‘The Family of the Infante Don Luis’ (1783–4) (lead image) is a whole novel in paint. The syphilitic late middle-aged Infante — younger brother of the king — plays patience by candlelight; beside him sits his beautiful, melancholy young wife. All around stand their entourage — among them a handsome, grinning fellow who may have been her lover.

At this stage, Goya’s ambition exceeded his ability. The picture, though haunting, is a spatially incoherent collage of separately studied figures. One of the pleasures of the exhibition is the way you can watch Goya slowly educating himself until he finally reaches full power in his 50s and 60s.

Goya’s ‘Countess-Duchess of Benavente’ (1785)

He felt he never did anything better than ‘The Portrait of Ferdinand Guillemardet’ (1798), the ambassador of the French revolutionary government in Madrid. It certainly is a perfect picture — the sitter coiled with vitality like a coldly efficient human spring, surrounded by delicate air and light. ‘The Duchess of Alba’ (1797), however, is more engaging: not only a noble heiress but a headstrong, vehement and glamorous presence (there was not a hair on her head, an observer noted, that did not awaken desire).

Goya’s ‘The Duchess of Alba’ (1797)

Goya’s (Lucian) Freud-like honesty about his sitters seems so clear in retrospect that it has always been a mystery why some of them put up with it. He clearly despised his last royal master Ferdinand VII, who looks sly, nasty, fat-faced and idiotic in the state portrait of 1814–15. And indeed, at that point, the contradictions of Goya’s position as court painter and fearless truth-teller became unsustainable. In old age he went into exile in Bordeaux.

Goya’s ‘King Fernando VII’ (1815)

Touchingly and inspiringly, he carried on evolving into his 80s. If some late works look strangely like Manet or Sargent, it’s because the artists of the future learnt so much from him. As you walk through the exhibition you see him turning himself from an awkward but talented provincial into a master, while simultaneously emerging step by step from the baroque past into the modern world. It’s that journey which makes Goya unique.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in