If there’s one thing people find annoying about classical music anoraks, it’s our passion for vintage recordings. ‘Listen to that ravishing rubato,’ we gush, as an elderly soprano swoops and scoops to the accompaniment of what sounds like a giant egg-and-bacon fry-up. And if non-anorak listeners do manage to ignore the pops, scratches and static, what do they hear? Wrong notes. Plenty of them. Is that really Artur Schnabel murdering the mighty fugue of Beethoven’s ‘Hammerklavier’ Sonata or is it Les Dawson?

There are actually two problems here — a disconcerting style of performance and crappy recorded sound. It’s important to distinguish between them. Those 78rpm records and the first LPs captured musical techniques that have died out across the board — in the opera house, concert halls and recital rooms. No one today can match the jubilant yet tortured cry of the Danish Wagnerian Heldentenor Lauritz Melchior, caught in his prime by HMV in the 1930s — and also hired to belt out ‘The Star-Spangled Banner’ at Dodgers baseball games in the 1960s after he became a US citizen. Partly this is because modern tenors know how dangerous it is to shout their way through Siegfried; in the old days a Heldentenor might work for 20 years but only be at his best for five of them.

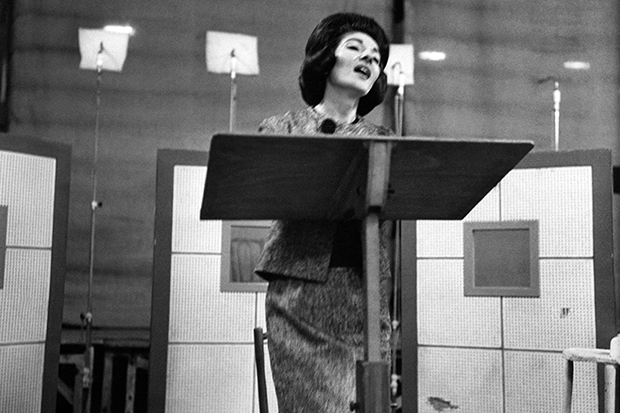

Likewise, if Maria Callas were launching her career today, her management wouldn’t allow her to take the self-destructive risks that meant she was beginning to burn out before she was 30 — and produced uniquely ugly as well as uniquely thrilling high notes. You never knew what was coming and neither did she. (After one particularly hideous squawk, a member of the audience threw a bunch of carrots on to the stage; she was so shortsighted that she picked it up delightedly.)

‘Her imperfections set her apart, and her ability to find the emotional meaning in a role was unsurpassed,’ says NPR’s arts correspondent Lynn Neary. Which, mutatis mutandis, is the reason to treasure all the best old recordings. The flaws are indivisible from the emotional meaning. This is true on a purely musical level. Those flubbed notes and cheeky deviations from the score reflect a devil-may-care nonchalance that would have Edwin Fischer or Pablo Casals thrown out of the first round of a modern competition. It’s also true on a technical level. Sound engineers at Abbey Road in the 1930s couldn’t patch over mistakes. And if in a live recorded concert one of the horn players screwed up the opening phrase of Schubert’s Ninth then the imperfection was caught for posterity.

But — and it’s a big but — some of the limitations of those recording techniques can now be transcended. Since the 1970s we’ve been manipulating sound digitally to ‘improve’ analogue recordings. I put ‘improve’ in inverted commas because bad digital remastering has done more violence to classical music than any number of Vanessa-Mae crossover albums. The market was flooded with cleaned-up historical performances that make scratched 78s sound even worse than they did originally. In their clumsy removal of pops and hiss, digital cowboys scraped off some of the music. Then they’d add brightness and reverberation. The result: Alfred Cortot playing the marimba.

Meanwhile EMI and its rivals issued their own official remasterings. Often these were nearly as bad as the cowboy CDs. Fortunately specialist labels such as Pearl, Biddulph, Music & Arts and Tahra noticed what was happening and adopted a new, light touch. Ridiculously light, in the case of Pearl, which kept the hiss rather than damage the ‘tonal bloom’. Critics complained about ‘a hailstorm of surface noise’. Enter Naxos, which cleverly signed up a world-famous restoration engineer, Mark Obert-Thorn, known as a ‘moderate interventionist’. He was responsible for Naxos’s much-admired Schnabel Beethoven set, which is pitched somewhere between the raw Pearl and the overfiltered EMI. The hiss is gentle rain, not a hailstorm.

When I bought the Obert-Thorn Schnabel I felt smug about owning the ‘right’ remastering. I rarely listened to it, however. Even though you soon stopped noticing the surface noise, there was a lingering sense of distance between listener and performer. But what do you expect from recordings made 80 years ago?

Yet, as I write this, I’m listening to Schnabel playing the ‘Appassionata’ and, despite a hint of fuzz, he’s in the room. In stereo, or something like it. An aural miracle has been performed — thanks to Andrew Rose, a former BBC studio manager living in the Dordogne. Rose is an expert in audio forensics. He was once asked by the Sun to investigate claims that a ‘new’ Michael Jackson soundtrack contained old material. (It did.) His label is called Pristine Classical and its catalogue contains so many marvels that I’ve become — slightly to his embarrassment, I think — the Pristine equivalent of an Apple fanboy.

You couldn’t call Rose a moderate interventionist. His signature technique is something called ambient stereo, which spreads mono sound between your speakers but far more subtly than the wretched ‘fake stereo’ of the 1960s. This is what gives his version of Furtwängler’s 1942 Beethoven Ninth — the most frightening you’ll ever hear — the edge over other excellent remasterings.

Then there’s ‘convolution reverberation’, in which the reverberant sound of a particularly fine concert hall or opera theatre is digitally modelled and applied to a recording. ‘The very dead acoustic of Toscanini broadcasts from NBC’s Studio 8H can come alive with a convolution reverberation derived from Birmingham’s Symphony Hall,’ says Rose. ‘And early Soviet opera LPs invariably sound better with a hint of the Sydney Opera House to round out the voices.’

Such boldness upsets audiophiles at the fundamentalist end of the spectrum, but Rose isn’t bothered. He relishes an argument: on the internet you can find him absolutely trashing Warner Classics’s new remasterings of Callas’s complete studio recordings, whose ‘improvements’ he reckons amount to little more than twiddling with the volume. Rose insists that he knows where to draw the line: he recreates what was lost in the recording process but would never correct a wrong note.

Make up your own mind by visiting his website, where whole movements can be sampled. Although Pristine makes compact discs for customers still attached to that dying intermediate technology — Pope Francis, a Furtwängler aficionado, owns CDs of Rose’s stunning remastering of the La Scala Ring Cycle — it mostly deals in downloads. No doubt other labels will quickly borrow Rose’s techniques for peeling the varnish off musical old masters, but that’s all to the good. The playing field will be levelled. Lovers of vintage recordings will find it much easier to demonstrate just how much passion and spontaneity were lost when orchestras were homogenised, opera singers learned to conserve their vocal resources and pianists moulded their style to impress competition juries. Anoraks, your time has come.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

New or existing Spectator subscribers are eligible for a 20-euro Pristine voucher. Visit new.spectator.co.uk/pristine and log in with your web ID to view this offer.

Culture House Blog: Eight remastered classical recordings you need to hear

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in