‘Sometimes, strolling through the ruins of earlier civilisations, we idly wonder what it must have been like to live through the end of one of them,’ writes Ferdinand Mount at the end of The Tears of the Rajas. ‘Now we know for ourselves.’

This is a long, wonderfully discursive and reassuringly old-fashioned book which tells the story of the British in India through the lives of one British family — the author’s ancestors, the Lows of Clatto in Fife. The Lows also happen to be the ancestors of Mount’s cousin, David Cameron.

The action opens in 1805, in the aftermath of the Second Maratha War, when the East India Company had established its dominant military position through most of the Indian interior. The narrative takes us through to 1905, just as it was becoming clear that, despite Curzon’s efforts, the Raj could not go on for ever and independence would sooner or later be inevitable.

At the centre of the book lies the quietly determined figure of General John Low, whose life spanned the century between 1788 and 1880. A cultured man who spoke fluent Persian, Hindustani and French, as well as being a talented flautist, the general was one of those people who had a talent for popping up in all the most important events of his age. Initially, as a junior officer, he was at the fringe of things, present but almost invisible at crucial moments in imperial history such as the Vellore Mutiny of 1806 and the little remembered but successful British invasion of Dutch-held Java in 1810–11. Few of hisletters survive from this period, so initially he is a somewhat ghostly figure, flitting in and out of a narrative dominated by his superior officers.

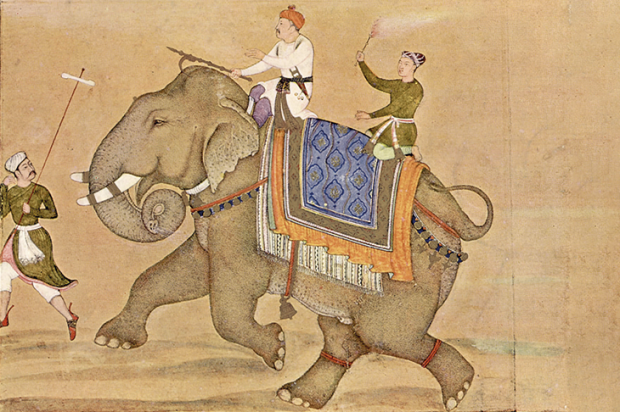

However, as he rose through the ranks Low became a more substantial presence, both in terms of determining events and in recording them in his own correspondence. By the middle of the book he has moved to centre stage, fighting in the Maratha wars, toppling in turn the Maratha Peshwa, the Rajah of Nagpur, the Rani of Jhansi and the Nawab of Avadh, advising against the First Afghan War and playing a crucial role in the brutal suppression of the Great Mutiny of 1857.

Through Low we witness the power of the East India Company growing with speed, as it dispatched its different Asian enemies one by one, its tentacles reaching across the globe, until it became by the end of the 18th century a major international player in its own right. To the east it ferried opium to China, fighting the opium wars in order to seize an offshore base at Hong Kong and safeguard its profitable monopoly in narcotics. To the west it shipped Chinese tea to Massachusetts, where its dumping in Boston Harbour triggered the American war of independence.

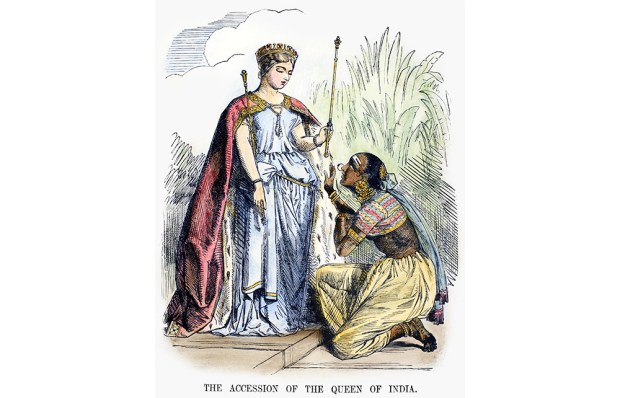

For it was not the British government that seized India, but an unregulated private company, headquartered in one London office. Mount writes:

The British empire in India was the creation of merchants and it was still at heart a commercial enterprise, which had to operate at profit and respond to the ups and downs of the market. Behind the epaulettes and the jingle of harness, the levees and the balls at Government House, lay the hard calculus of the City of London.

By early 1857, the Company directly ruled about two thirds of the subcontinent, had trained up a private army of around 260,000 — twice the size of the British army — and was able to marshal more firepower than any nation state in Asia. It was ‘an empire within an empire’, as one of its directors admitted, and by the early 20th century, ‘Company shares were a kind of global reserve currency.’

Mount relates this remarkable story with a gentle wit, a lightness of touch, a boyish enthusiasm as well as a genius for the telling pen-portrait. His writing has a charm that makes even the most meandering digression a pleasure to read, even if his style occasionally veers towards the Victorian, perhaps in sympathy with his sources. Spellings of Indian names frequently cling to their 19th-century British manglings, so the beautiful and sacred Narmada river is here referred to, somewhat eccentrically, as the ‘Nerbudda’. Indians are often ‘natives’, people who have the temerity to oppose the British are ‘the enemy’, unless they are Marathas, in which case they are, in addition, ‘fierce little warriors’ whose rajas are often ‘ghastly characters’ or ‘remarkably nasty pieces of work’, who indulge in ‘treachery, murder, especially fratricide, slaphappy extravagance and debauchery, only tempered by equally extravagant religious observances’.Their attempts at unified action ‘bore less resemblance to a confederacy than they did to a sack of rabid ferrets’.

Nevertheless, despite a fondness for such language, The Tears of the Rajas may not be a good present for patriots with high blood pressure, for some of its revelations will probably alarm dewy-eyed empire nostalgists. While Mount is often amazed at the scale of the heist his Scottish forebears pulled off in India, his story, like some great Indian river slowly winding its way through the plains, is in no hurry to reach its destination; and while it certainly washes its way past wonders, it also takes us past banks filled with pyres of burning bodies.

The horrors begin early and continue popping up in chapter after chapter. At the end of the Vellore Mutiny, 300 mutinous sepoys who surrendered were hustled into a fives court where they were tied together and gunned down at a range of 30 yards. The horrors continued as Java was invaded, and various Indian princely states were overtaken and annexed. The violent climax came with the Great Uprising of 1857, when the Company found itself threatened by the largest and bloodiest anti-colonial revolt against any European empire anywhere in the world in the entire course of the 19th century. Of the 139,000 sepoys of the Bengal army all but 7,796 turned against their British masters. In many places the sepoys were supported by widespread civilian rebellion. Atrocities abounded on both sides, but the British crushed the uprising with a particularly merciless severity.

The bloodiest moment of all came in September 1857, when British forces attacked and retook the besieged city of Delhi. They proceeded to massacre not just the rebel sepoys but also the ordinary citizens of the Mughal capital. In one neighbourhood alone, Kucha Chelan, some 1,400 unarmed citizens were cut down. ‘The orders went out to shoot every soul,’ recorded one young officer. ‘It was literally murder.’ Delhi, a bustling and sophisticated city of half a million souls, was left an empty ruin. In the aftermath, Low’s son-in-law, Theo Metcalfe, turned into what today we would call a war criminal, shooting and hanging survivors with abandon:

Theo erected a gallows in the grounds of Metcalfe house made out of the blackened timbers of his beloved home… Refugees sheltering in mosques would be plucked out and executed.

The general’s son, William Malcolm Low, was also implicated in the mass hanging of civilians.

It is a remarkable story, and cumulatively amounts to an epic panorama of British Indian history much more substantial than the ‘collection of Indian tales, a human jungle book’, which Mount modestly describes as his aim in the introduction. Instead it shows, as well as any book I’ve ever read on the subject, how much Britain lost in 1947 as the Indian empire imploded — but also the jaw-dropping scale of the violence, cruelty, racism and war crimes it had taken to found and maintain that Raj by brute force. For we must never forget that, in the final analysis, our empire was built by the sword and erected over the dead bodies of tens if not hundreds of thousands of our Indian subjects.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Available from the Spectator Bookshop, £20 Tel: 08430 600033

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in