Margaret Cavendish, the 17th-century Duchess of Newcastle, has been described as a heroine whose every doing ‘is romantic’ (Samuel Pepys); as being ‘so distracted… that there are many soberer people in Bedlam’ (Lady Dorothy Temple); as looking like ‘a devil in a phantom masquerade’ (King Charles II); as ‘the great atheistical philosophraster’ (anonymous 17th-century gossip writer); as ‘a picture of foolish nobility’ (Horace Walpole); as ‘a giant cucumber’ (Virginia Woolf); as a ‘crack-brained, bird-witted… fantastical… crazy duchess’ (Woolf again) and as ‘the empress and authoress of a whole world’ (herself). She has been seen as that most tiresome of types, a ‘character’. But in this erudite and entertaining book, Francesca Peacock makes a persuasive case for her being, as well, an author whose work is as illuminating as it is unconventional.

Margaret loved to make a spectacle of herself. Peacock begins with a visit she made to London in 1667. She attended the opening of one of her plays, arriving in a chariot drawn by eight white bulls, with her breasts bared and her nipples painted scarlet. When she drove to court wearing a man’s jacket in black velvet, some hundred boys and girls ran behind her silver-ornamented carriage whooping and pointing. She was a ‘pageant’, wrote one man-about-town. But she was also a daring thinker, who refused to accept the snubs of the male-dominated establishment. That same week she attended a meeting of the Royal Society, the first woman to do so.

At a time when most female authors (whose books, writes Peacock, made up just 1.3 per cent of all those published) used the coy byline ‘A Lady’, Margaret wrote proudly under her own name, and commissioned engraved frontispieces for her works in which she appears flanked by Minerva, goddess of wisdom, or adored by putti who crown her with wreaths of bay. She wrote treatises in iambic pentameters in which she came as close as anyone in her era to quantum physics. She could switch from factual narrative – a biography of her husband – to phantasmagorical fiction or polemical plays challenging misogyny. The Earl of Clarendon paid her the exasperating compliment of refusing to believe she had written her books: they were just too clever to be a woman’s.

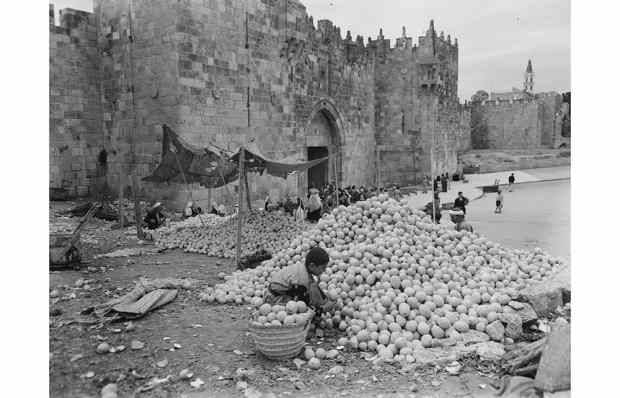

She was born Margaret Lucas in 1623, into a well-off family, but when civil war broke out no one was secure. Her brothers left to fight for the king and the family home was stormed by a parliamentary army. The soldiers dug up the chapel vaults and made themselves wigs of hair cut from the corpses of her recently dead mother and sister. Aged 20, Margaret made her way to Oxford, where the king had his headquarters, to become maid of honour to Queen Henrietta Maria and soon follow her into exile in France.

There she met the newly widowed William Cavendish, the future Duke of Newcastle. He was 30 years older than her (Peacock nods to modern sensibilities by describing the age gap as ‘slightly unsavoury’), and he was under a bit of a cloud in royalist circles for fleeing abroad rather than staying to fight. He had left all his estates and wealth behind him. In Paris he had to ask Margaret to pawn her clothes to pay for their dinner. He was, as she was too, plagued by ‘melancholy’ and ‘black bile’. But, for all these drawbacks, they were happy. He wrote her 70 poems in as many days, telling her she was ‘graced like a goddess, born by angels’ wings’. Within months they were married.

They moved to Antwerp, where they rented Rubens’s house. There William introduced Margaret to his scholarly acquaintances, Thomas Hobbes and Descartes among them. She discovered how thrilling intellectual pursuits could be. Soon she was writing essays, allegories and discourses –freeform pieces into which she was able to pour her creative energy. Her melancholy dropped away.

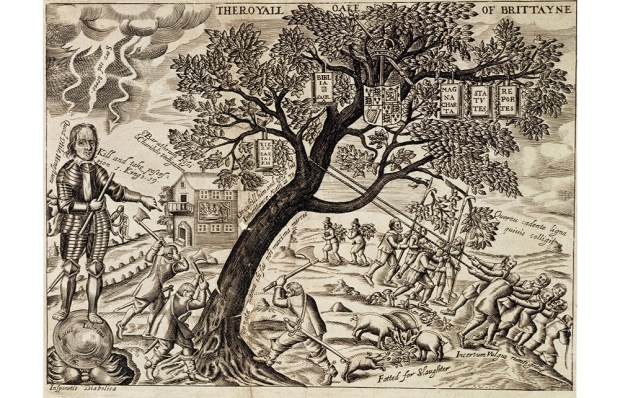

Despite Peacock’s subtitle Margaret was far from being revolutionary in the normal sense. She believed unquestioningly in a social order within which each person lived according to their ‘quality’. To her the civil war was the consequence not of a thirst for rights and liberties but of republicans’ ‘factious sores and feverish ambition’. If her politics were conservative, however, her imagination was untrammelled by conventional pieties and her mind roamed free over science and philosophy (the two disciplines were not then distinct).

She wrote poems about fairies which, far from being fey, were metaphorical accounts of ‘atomism’, an approach to physics that derived from the Epicureans and was at the forefront of 17th-century scientific thinking. Angrily alive to the injustices done to her sex, she played in her dramas with ideas about lesbian separatism and polyamory. Her satirical fantasy novel The Blazing World has been described as the first work of science fiction.

Peacock plaits a great deal of other material into her biography. Life and literature mirror each other. When Margaret and the rest of the queen’s household were en route to France, they were fired on by a parliamentary ship and blown 300 miles off course. Peacock points out how often Margaret’s fictional characters endure storms and attacks, and juxtaposes themes from her life, or her work, with their echoes in other women’s stories. Margaret wrote a play, Bell in Campo, about a lady who follows her husband to war, at the head of a troop of other ‘noble heroickesses’. Peacock interweaves an account of the play with stories of real women – many cross-dressing to avoid detection – who fought in the civil war. Margaret had no children – and Peacock tells us about contemporary remedies for infertility and gives us instances of women grieving over their dead babies.

She also writes about female highwaymen, hypochondria, microscopes, the publishing trade and the comparatively enlightened views on gender roles of Dissenters. Margaret is always the star of the show, but Peacock gives her a backing troupe of other female writers of the period, other childless women and other wives for whom marriage, however comfortable or loving, was oppressively unequal. ‘All wives,’ wrote Margaret, ‘if they be not slaves, yet are servants.’

The 17th-century parallels enrich and amplify Margaret’s story, but Peacock’s efforts to situate her within the canon of feminist literature are less interesting. The usual suspects are brought on – from Christine de Pizan to bell hooks – whether or not their appearance adds much. It’s always good to be reminded of Villette – it’s one of my favourite novels too – but it doesn’t belong here. Nor do we need so much detailed textual analysis of Margaret’s writings.

Better too much than too little, though. Margaret had ‘doubts of an after-being’ and her candid admissions of disbelief in Christian doctrine startled her contemporaries. Not counting on heaven, she craved the other kind of immortality. ‘All I desire is fame,’ she wrote. She would have been downcast to know how nearly she has been forgotten, but delighted by this sympathetic account of her eventful life, her brave and wayward personality and her fantastically idiosyncratic writings.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in