As this country stumbles towards a Labour victory at the next election, the mood on the left remains subdued. The problem is not Keir Starmer’s personal charisma, achingly absent though that may be. No, it lies much deeper than that, in what Tony Benn liked to call the ishoos. The cry goes up from focus groups across the land: what does Labour really stand for? What are its Big Ideas? Does anyone know?

Well, perhaps they will quite soon. Step forward Daniel Chandler, a Cambridge-educated policy adviser and think-tanker who is now completing a doctorate at the LSE. The pre-publicity for his new book, with glowing eulogies from Thomas Piketty, Amartya Sen, Rowan Williams and other grandees, plus those well-known political theorists Zadie Smith and Stephen Fry, suggests that (a) he is very well connected; (b) this is a truly compelling work; (c) the psychology of wish-fulfilment has turned this book into an answer to a prayer. Answers: (a) don’t know; (b) not really; (c) very probably.

At one level, Free and Equal does read like a grand programme of policy proposals, or perhaps a job application for senior policy adviser at Labour HQ. Chandler traverses a range of political, economic and social issues, suggesting one reform or innovation after another. The manner in which he does this is impressive; he writes with great clarity, avoiding wonkish jargon, and his prolific end-notes show that he has processed huge amounts of academic analysis, albeit the sort of analysis that tends to support his argument.

Many of these policy proposals are familiar ones, and the reasons in their favour are mostly familiar too; the standard reasons against them are treated more summarily, or sometimes not at all. Chandler explains, for example, that we need a written constitution to protect our liberties. As it is, ‘the most important legal protections for basic rights and freedoms are set out in the Human Rights Act’ which could be overturned in parliament tomorrow. (Does he really think we had no legally protected basic rights and freedoms before 1998? The mind boggles.)

We need, of course, proportional representation. Party funding should be reformed. Companies should be forbidden to donate at all, though money from trade unions and ‘mass-membership advocacy groups’ would be fine. Most funding should come from the state handing every adult an annual £50 ‘democracy voucher’ to give to their preferred party – a scheme which, I calculate, could cost roughly £2.6 billion a year. And in addition we need randomly selected ‘citizens’ assemblies’; we could even have a big one and make it a new House of Parliament. (Chandler adds: ‘The discussion should be guided by experts who can provide unbiased information about the subject at hand.’ Ah yes – what could possibly go wrong?)

In the field of education, the most eye-catching proposal is the abolition of fee-paying schools. Pre-school education for all children, starting preferably as soon as their mother’s maternity leave ends, is another priority. That last proposal is not costed, but, however expensive, it must be minnow-sized compared with the two biggest items here. A Universal Basic Income, set if possible at 60 per cent of average income, should be given to all adults, whether they choose to work or not; and this could be supplemented by a Universal Minimum Inheritance of, say, £100,000, awarded to everyone on their 18th birthday.

Chandler’s command of the secondary literature in favour of these measures gives him an enviable confidence when it comes to pooh-poohing their possible ill effects. Universal Basic Income would not be risky at all, apparently: ‘Despite critics’ fears, there is no reason to think that people would leave work en masse.’ One wonders whether the UK’s post-Covid experience may have given us approximately 500,000 reasons.

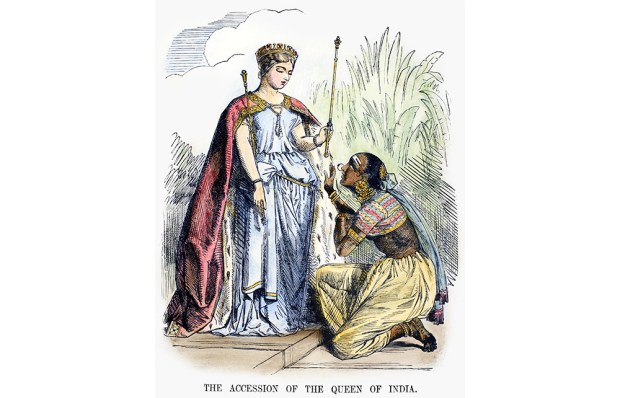

Chandler claims to be a realist utopian, which means that he knows this must all be paid for. He offers no detailed costings for many of his proposals – including guaranteed minimum interest rates for savers, and payments to black people to redress past wrongs – but states rather breezily that the tax burden will need to go up from its current 33 per cent of GDP to somewhere between 45 and 50. The way to do this is simple: increased Capital Gains Tax and taxes on dividends, higher bands of income tax up to 75 per cent and of inheritance tax up to 90 per cent, and, above all, a Pikettian annual wealth tax, with bands rising from 2 per cent to something above 6. Once again, ‘it seems unlikely’ that this would act as a disincentive to entrepreneurs. And don’t worry about them leaving the country: there is ‘little evidence’ of people moving for such reasons, and if they do, we can always hammer them with an ‘exit tax’ and limit their right to return.

You are probably thinking that Labour would be mad to adopt this exorbitant wish list. Yes indeed, as it stands; it would need to be heavily diluted. But the under-lying argument will appeal strongly to post-Corbyn, non-Corbyn Labour. It is leftist and ‘progressive’ (as you may have noticed), but it is not socialist. Chandler rejects the nationalisation of industry and defends the market economy. He also calls for ‘liberal patriotism’, and even raises some arguments against mass immigration.

Above all, he has a Big Idea, which is that we should be guided in all these matters by the American philosopher John Rawls (1921-2002). Rawls was both a liberal and an egalitarian who nevertheless defended the market economy. His famous thought experiment involved people having to choose the best way of organising society while standing behind a ‘veil of ignorance’ – that is, without knowing whether they would turn out to be at the top or the bottom of the pile. He argued that they would want equality in some basic goods, and full equality of opportunity, but they would accept the inequalities of a system such as the market if it benefited everyone in the long term.

As Rawls developed his theory, it turned into a general account of essential human goods and rights. The whole scheme, summarised by Chandler, is highly elaborate, with political, personal and economic freedoms, basic needs, primary goods and various basic principles, some things trumping others according to certain rules of priority. Waddingtons would probably reject the board game version on grounds of excessive complexity.

Chandler emphasises, correctly, that the thought experiment was not offered as a demonstration that all these things must be true. It was an illustrative device, to clarify the underlying values which, presumptively, we must share. And indeed when you turn the handle on such a device, what comes out depends very much on the assumptions you fed into it – in this case, those of a 1970s liberal Harvard professor. The most basic Rawlsian rights concern developing our moral ‘capacities’ to think about what is good, and ‘to form our own view about how w e should organise society’. In the pubs of Huddersfield and Barnsley they speak, I believe, of little else.

Complexity breeds ambiguity, which means that you can sometimes justify quite contrary things on Rawlsian grounds. Thus Chandler assures us that positive discrimination can be perfectly compatible with equality of opportunity. But on some major issues, such as abortion, Rawls’s patent machinery generates no real answer at all. Democracy is granted a role in such cases, to tidy up or fill in the details. And, in general, democracy here, although valued highly in theory, seems in practice largely a vehicle for delivering and fine-tuning Rawlsian policies.

Chandler claims to be a bringer of values, to fill the vacuum at the heart of our politics. People have lost faith in democratic politics, he says, seeing it as technocratic and dominated by dogmatic ‘neoliberalism’; looking up hungrily and not being fed, they have turned to evil populists instead. I hold no brief for authoritarian populism, but I wonder if his analysis is correct – partly because his account of neoliberalism is a caricature, partly because his own elaborate scheme for government to reorder our lives may turn out to be more like techno-cracy than he realises, but also for another reason. Is it not possible that voters for populist parties have been put off not by a vacuum of values but by the imposition on them of some quite specific values of a thoroughly ‘progressive’ kind?

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in