What happens to an artist’s reputation when he dies? Traditionally, there was a period of cooling off when the reputation, established during a lifetime, lost momentum and frequently collapsed, quite often presaging a long fallow period before reassessment could take place. The Pre-Raphaelites suffered this to a very pronounced degree. Famously, Andrew Lloyd Webber tells the story of buying his first Victorian pictures for pocket money in junk shops, and just missing Lord Leighton’s ‘Flaming June’ because he didn’t have the £50 asking price.

Closer to our own time, when Graham Sutherland died in 1980 his reputation plummeted terribly, having for years been overinflated by a loyal European market that bought him at increasingly high prices. (The Italians, rather unexpectedly, were particularly fond of his work.) His paintings and drawings have gradually regained their value and now he is riding high again. But the once sought-after later graphic work remains inexpensive, to be picked up for bargain prices. Among his prints, only the densely romantic early etchings hold their own at auction.

With the increasing commodification of art, the situation has polarised. Art is now such big business that the market cannot afford to let the standing of an international property such as Bacon or Freud slump: or perhaps it is just too soon for them to be seen as other than highly bankable. But Bacon has been dead now for a dozen years and in the past that has been long enough for the tide of taste to turn once the artist is no longer there to dominate it. The truth is that finance rules the market to a far greater degree now than 30 years ago and reputations are artificially sustained for the protection of investments. The Bacon industry is booming, with the huge project of a catalogue raisonné well under way, and prices continuing to rise. Will there ever come a point where Bacon falls from fashion? I’m sure there will, but not in any cultural or financial context easy to envisage.

So the posthumous way forward for an artist these days is to have a cadre of investor-collectors and a proactive gallery to keep your name prominently before the public. Of course, this is not always easy to achieve. There are still a number of good artists’ estates out there that remain unexposed, their owners or guardians perhaps dreaming of greatness. Quite often the inheritors are unsure how to proceed, and fear what they imagine as the asset-stripping of voracious dealers. This can of course happen, and many an artist’s studio has been cherry-picked by a wily commercial practitioner with an eye for the main chance. But it’s not always the case.

Hoyland would have been 80 on 12 October, and there are various celebratio

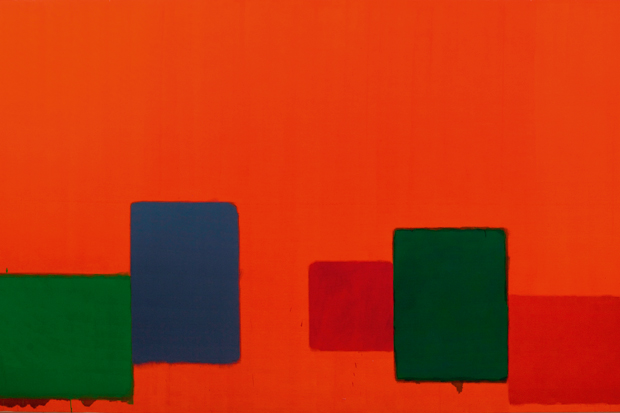

ns afoot. At the moment there is no powerful gallery representing Hoyland’s work worldwide (though rumour has it that an announcement on that front will not be too long deferred), and the main news is closer to home. In recent years, Damien Hirst has become an admirer and collector of Hoyland’s paintings, buying a substantial holding of the artist’s finest work. The news is breaking as I write this piece that the Hoyland estate is in conversation with Hirst regarding a John Hoyland retrospective, scheduled for early summer 2015, as the inaugural show at Hirst’s new gallery in Lambeth. This is great news: whatever you think of his art, Hirst is proving himself a collector of flair and determination, and it may well be that his most lasting achievement will be as a curator. After all, he first came to prominence in the dual role of curator and artist with the group exhibition Freeze in 1988.One artist’s estate, whose executors have taken much thought for the future, seeking advice over a wide field, is that of John Hoyland. Hoyland (1934–2011) was an abstract painter of international standing, a wonderfully inventive colourist with a witty and restless intelligence who latterly used texture in acrylic paint with unprecedented boldness. His estate is run by Beverley Heath-Hoyland, John’s glamorous widow, a former Jamaican beauty queen, who has been promoting his interests since his death and has already done sterling work. Much has been achieved on the cataloguing and archive front, for Hoyland left a considerable body of paintings from various periods of his career. A film project is under way to record his life through the memories of friends and contemporaries; a scholarship has been set up in his name at Chelsea College of Arts; and the John Hoyland Trust has announced it is building two classrooms for Anchovy Primary School in Jamaica. For Hoyland, Jamaica was a second home and he visited it regularly. Beverley says, ‘John loved going to the tropics and waking up to this wonderful light. He called it “visual poetry”. He loved watching the hummingbirds and the butterflies whizzing around, the lizards pretending to be dead. He loved it all. And it fed through into his work.’ Heath-Hoyland is determined to give back in memory of her husband, not just promote his undoubted genius.

Meanwhile, Hoyland’s star is rising elsewhere. Throughout August, his painting ‘Memory Mirror’ (1981) was hung at the Fitz-william in response to its resounding popularity in the ‘Art Everywhere’ campaign (the national outdoor art exhibition, with art on posters and billboards). Hirst was quoted in the publicity as saying: ‘In my eyes John Hoyland was by far the greatest British abstract painter and an artist who was never afraid to push the boundaries.’ And the recent spate of TV programmes investigating abstract art has featured the fascinating 1979 Arena film of him at work, while novelist Colm Toíbín has gone on record as saying, ‘I keep seeing John Hoyland paintings and I keep thinking “Why isn’t this man one of the best-known figures of the English 20th century? Why isn’t there a John Hoyland room?”’ Well, there’s a thought. It was an American artist, Robert Motherwell, who suggested that Hoyland could be the new Turner.

It’s time we got the chance to see if that’s really the case.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in