In 1963 two Hamlets went into production: one directed by Laurence Olivier, the other by John Gielgud. The situation had been engineered by Richard Burton and Peter O’Toole. The story goes that while shooting the film Becket, Burton and O’Toole had decided they should each play the Prince under either Olivier or Gielgud and they tossed a coin over who would get which director. O’Toole got Olivier; Burton got Gielgud.

Both productions – booze-drenched affairs – went ahead, but the Hamlet that became a showbiz legend was Burton’s doomed Dane.

Burton looked up to Gielgud. He had played Hamlet a decade before, and in it he copied Gielgud’s word elongation (‘In a dreeeeam of passion’). Gielgud, for his part, was keen to stage something for the 1964 Shakespeare quartercentenary and liked the poetic, dark pessimism of the starry Welshman. As director, he decided that his brilliant new concept for Hamlet was… no concept. No tights (good move; Burton hated them), no decor, nothing. It was to be staged to look as if it was the last run-through before the dress rehearsal. The largely American cast was invited to wear anything – pyjamas and bikinis were ruled out but otherwise it was come as you like.

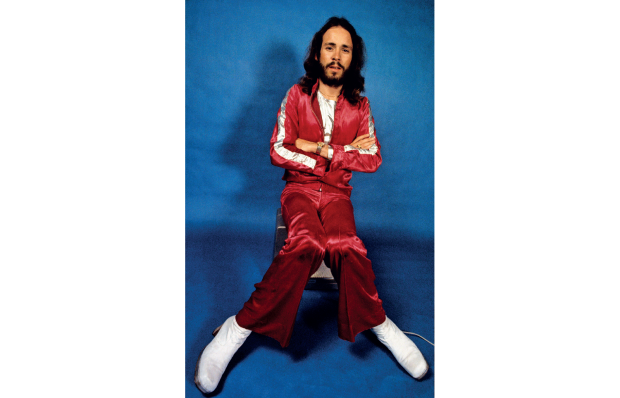

The show opened on Broadway at the Lunt-Fontanne Theatre after previewing in Canada. What became known as the ‘Liz and Dick’ show thoroughly upstaged the play. The police closed off roads but the kettled fans broke free and chased the stars’ limo. Taylor and Burton were at peak fame having recently filmed Cleopatra, an insane epic of exceeded budgets, lawsuits, adultery and diamond shopping. (Taylor famously had a donkey’s appetite for carats.) The pair tied the knot – it was her fifth marriage – during the run. When Burton said Hamlet’s Act Three line, ‘I say we will have no more marriages,’ he got a great round of applause.

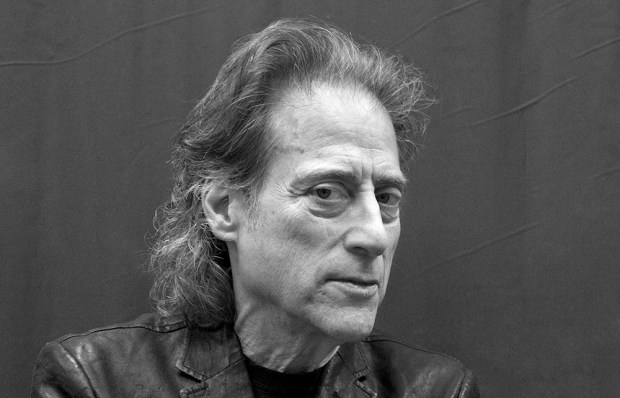

The fraught, botched production of Hamlet is now the subject of a new play at the National Theatre called The Motive and the Cue (taken from Hamlet’s line about the Player King: ‘What would he do,/ Had he the motive and the cue for passion/ That I have?’) starring Mark Gatiss as Gielgud, Johnny Flynn as Burton and Tuppence Middleton as Taylor. It is directed by Hollywood favourite Sam Mendes.

Gielgud turned 60 during the original project and was the epitome of the old school of acting. His mellifluous voice, shimmering with emotion and delivered with what one critic called a ‘parsonical quiver’, was famous. Burton’s voice – a spine-tingling poetic rumble of shifting coal slag – was more rugged, more 1960s, and no less adored. Gielgud had encouraged Burton’s first Hamlet in the 1950s and he was a bit unhappy about it. In one of his famous gaffes, he called at Burton’s dressing room as he was getting out of costume and said: ‘Shall I wait until you’re better?… I mean ready?’

For source material about the show, Jack Thorne has used verbatim conversation from the rehearsals secretly recorded with a tape machine smuggled in a briefcase, von Stauffenberg-style, by the actor Richard L. Sterne (playing a bit part) who typed up Gielgud and Burton’s long private meeting and later produced a book based on their exchanges. William Redfield, the actor playing Guildenstern, also published a book, Letters from an Actor, consisting of incisive, bitchy epistles about the awkward rehearsal process.

Part of the problem was that Gielgud knew by heart every single line of the play thus unsettling the cast. Burton was, of course, sloshed from beginning to end. (A famous Burton cocktail recipe of the day was ‘First take your 21 tequilas…’ ) Liz Taylor – who became a fond stage groupie – nursed him tenderly but was not always great for his morale, saying teasing things to the cast such as: ‘Does the burnt-out Welshman know his lines?’ He didn’t.

Gielgud was prone to saying what he really thought accidentally: ‘Really splendid tonight, Richard… The entire section we spoke of from “To be or not to be” through to the nunnery scene was excellent, excellent – I almost liked it.’ Burton, an actor perhaps temperamentally unsuited to the part of a dithering Dane, listened very politely but had his own views. ‘John, dear, you are in love with pronouns but I am not.’

Thorne’s play features Janie Dee, perhaps the most experienced member of the cast. She is playing Eileen Herlie (1918-2008), an actress of Glaswegian origin who was cast as Hamlet’s mother Gertrude despite only being seven years older than Burton. Olivier had phoned her saying: ‘Eileen, we are going to do this with Freud’s Oedipal complex in mind.’ She said: ‘Oh, what a good idea, Larry.’ Then she hung up, called a friend and asked: ‘What’s an Oedipal complex?’ When she played the part again, Gielgud privately described her and the man playing Claudius as looking like ‘an ex-croupier from Monte Carlo who has eloped with a fat landlady’.

‘Eileen Herlie is somebody we should know about,’ argues Janie Dee. ‘Eileen had already played Gertrude. She’d been rightly much praised for the part and her experience of working with Olivier was very good. She didn’t really need to do it again. Any problems between Burton and Gielgud are really painful to her in our play. She wants to make sure nobody gets above themselves. We get to see what really goes on in a rehearsal room – and of course there’s lots of conflict. But I can’t reveal more!’

Did she ever meet Gielgud or Burton? ‘No. But my mother sat on the stairs at home after seeing Burton in Coriolanus and wept because she knew she would never marry him. I’ve watched every interview with Burton I can. It was just such a shame he died at 58.’ Given the choice, would she prefer to have had dinner with Gielgud or Burton? ‘Burton – I’m with my mum on that score.’

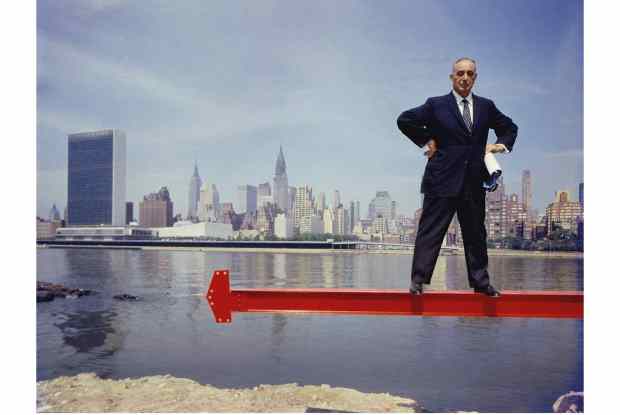

Gielgud learned to loathe the clamouring crowds that, as he saw it, undermined the play itself. You might think that Gielgud, who represented the most elitist end of the English stage, would have raised American hackles. But it turns out he was much loved by the method school of mumblers. Marlon Brando was Mark Antony in the film that he and Gielgud did together of Julius Caesar (Burton turned the part down), and Gielgud helped him out with his speeches. The young beat-era Brando in turn loved Gielgud’s brand of elegant reserve, announcing: ‘That cat is down.’ Lee Strasberg, one of the great gurus of the method, had been to see Gielgud’s Hamlet in the 1930s and was mesmerised by his capacity to inhabit Hamlet’s mind: ‘When Gielgud speaks the verse, I can hear Shakespeare thinking,’ he declared.

The Burton Hamlet wasn’t over-burdened with thought; nor was it helped by Gielgud’s chronic indecision and his odd suggestions (‘Try wearing a hat,’ was one note he gave an actor desperate for help). The show on Broadway, however, made a fortune; it was probably the most profitable Shakespeare ever staged. Gielgud – who voiced the Ghost for the show – summed up Burton as ‘shrewd, generous, intelligent and co-operative. I grew very fond of him’. But he privately admitted he was no Hamlet as he never had the princely bearing required. The crowds didn’t agree. When Gielgud played the part, he got 20 curtain calls a night and invariably missed his bus home. Burton, however, staggered through 138 performances, narrowly breaking Gielgud’s record to the latter’s mild upset. Burton’s Hamlet was an artistic flop that utterly triumphed.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in