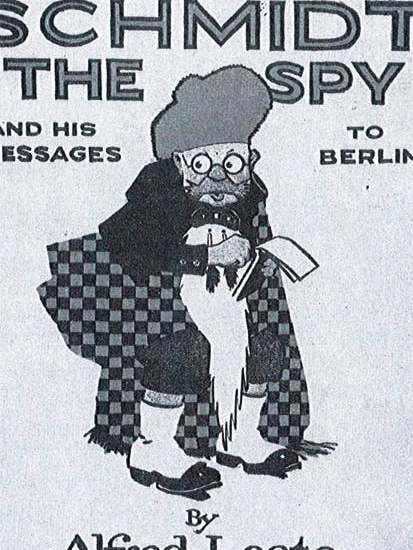

There can’t have been this many books about the first world war since — just after the first world war. One publishing craze of the 1920s was books about spying, in which retired war spooks gave away their trade secrets and told tall stories about dead-letter drops and invisible ink.

Melanie King has read them all, filleted them and collated her researches in Secrets in a Dead Fish (Bodleian Library, £8.99, Spectator Bookshop, £8.54). ‘Ingenious methods of communication were developed,’ she writes. ‘The entire Western Front, from its windmills to its laundry lines, must have seemed charged with secret meanings.’

This is Le Carré, but a Janet and John version. Men stand around in hotel lobbies saying things like, ‘I wonder if Mr Jim has called for that letter?’ Telegrams are ingeniously coded, so that ‘Bertha’ means a battleship, ‘Sarah’ a submarine and ‘Dora’ a torpedo boat destroyer. Spies drink shampoo to feign illness, steal the identities of men who die in the next hospital bed, infiltrate munitions factories in order to sabotage the other side’s weapons. Everyone is listening in to everyone else’s telephone conversations in the field. (The Americans use native Navajo speakers to confound the Germans, entirely successfully.) If you have to go drinking with other spies, glug down a four-ounce bottle of olive oil first: it will line your stomach and keep you sober.

It’s all wonderful stuff, alternately ludicrous and completely believable, and sometimes, triumphantly, both.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in