Last year saw the centenary of the London Group, a broad-based exhibiting body set up in a time of stylistic ferment in the art world as an independent alternative to the closed shops of the academies. Formed from the amalgamation of the Allied Artists’ Association and the Camden Town Group, it boasted such notable founder members as Lucien Pissarro and Walter Sickert, while Jacob Epstein is credited with naming it. Inevitably, the London Group has gone through innumerable highs and lows in its 100-year history, yet the mere fact that it still exists is testament to the enduring need for such an independent collective. The Ben Uri, itself an outsider organisation, was founded in London’s East End Jewish ghetto in 1915, two years after the LG, also (as Ben Uri chairman David Glasser points out) ‘in response to establishment prejudice and exhibiting restrictions’. It was dedicated to giving young Jewish artists a chance, and among its first stars were David Bomberg, Epstein, Mark Gertler and Jacob Kramer. The overlap with the LG is at once apparent: all four are featured in the Ben Uri’s fascinating exhibition.

It was a sensible move to concentrate on the first 50 years of the LG and not to attempt the full 100: the early years are by far the most interesting in the group’s history, and the format of selecting one artist to cover each year allows the exhibition to have a coherence and cogency that is itself impressive, given the somewhat sprawling and all-inclusive nature of this exhibiting body. Of course it would be possible to quarrel with the selection — I personally would have dispensed with Roger Fry, Duncan Grant, Rupert Lee, Edna Manley, Hans Feibusch and Dorothy Mead, and would have liked to see substituted John Nash, William Gear, Craigie Aitchison, Leonard Rosoman, Patrick George and Anthony Eyton. But there are enough works by indisputably good artists to ensure that visiting this exhibition is a very considerable pleasure as well as an education.

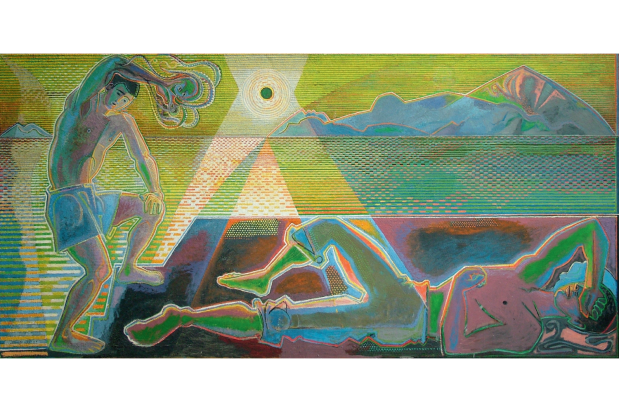

The exhibition takes its name from the uproar caused by, specifically, Mark Gertler’s odd and rather Blakean painting ‘The Creation of Eve’, 1914, exhibited in the third London Group show the following year. It was wartime, and newspaper articles tended to the conservative and jingoistic. Gertler’s visionary painting was thought to be unpatriotic, indecent and subversive, and he was accused not only of sensationalism but even of blasphemy. It is still an arresting picture, and it has been cleverly hung on a return in the middle of the left-hand wall of the gallery so that it greets the visitor. There’s a fine group of supporting paintings hereabouts:next to the Gertler is a colourful rendition of Swiss Cottage (nicely local subject for the Ben Uri) by the Polish artist Stanislawa de Karlowska, often overlooked as she was married to the brilliant Robert Polhill Bevan. His painting of a horse sale at Tattersalls, a typical subject, hangs next to his wife’s, and is in turn supported by an intensely bright but not gaudy Spencer Gore of Harold Gilman’s house in the new garden city of Letchworth. Gilman’s own ‘Portrait of Sylvia Gosse’ is here, as is a superb interior by Ethel Sands, entitled ‘The Pink Box’. What restrained richness — it’s surely time for another look at this artist; when was the last Ethel Sands exhibition?

There are several pieces of sculpture in this room, the most dramatic being the strongly chopped and simplified ‘Seated Torso’ by Frank Dobson, in Ham Hill stone, and placed in a vitrine by itself. Gaudier-Brzeska’s ‘Bird Swallowing a Fish’, although a powerful work, is more familiar than the underrated Dobson, and has been placed in a cabinet with Epstein’s obscure ‘Flenite Relief’ that actually makes both pieces difficult to see properly. Of the other paintings in this ground-floor gallery, there’s an intriguing nude by Frederick Etchells, better known as an architect than painter, all scarified surface and compressed forms, a modest-sized Wyndham Lewis work on paper from c.1912, a small etching by C.R.W. Nevinson, and a stark and troubling image by Jacob Kramer called ‘Clay, or The Anatomy Lesson’ (1928). On the end wall in glory is hung Matthew Smith’s vibrantly coloured ‘Fitzroy Street Nude No. 2’ (1916), a real corker of a painting, and one of the show’s many high spots.

Downstairs are more delights. At the foot of the stairs is a surprisingly tender and lyrical (if a bit pallid) Victor Pasmore abstract, a lithograph that was reproduced as a poster for the 1948 LG Annual Exhibition. At one end of the main room is a majestic barbaric head by Eileen Agar, a 1930s painting called ‘The Modern Muse’, very Picasso-esque, while at the other is a rather dark landscape by Ivon Hitchens from 1955, not one of his finest works. To the left of the Agar is a classic Paul Nash painting, a great structural and imaginative work entitled ‘Northern Adventure’, with a tough Henry Moore cast concrete ‘Head of a Woman’ in between. On the other side is the 1928 Pentelicon marble ‘Mask’ by Barbara Hepworth. Here, too, is the magnificent Bomberg from the Ben Uri’s own collection, ‘Ghetto Theatre’, with an equally fine William Roberts painting, ‘At the Hippodrome’ (1920–1), next to it; also Sickert’s ‘Portrait of Cicely Hay’ (1922–3), still rather shocking given conventional notions of female beauty.

There’s a nice little linocut by Paule Vézelay, but being figurative it gives no indication of her later notable development as an abstract artist. In the middle of the room is a large and beautiful sculpture by Gertrude Hermes: a flowing walnut carving of a butterfly — a most distinctive piece. I quite liked Edward Wadsworth’s tempera painting of a Marseilles street scene but, for anyone who knows his drawings of the same subject, they have more spontaneity and directness. There’s a lively ink and watercolour drawing of ‘Two Costers in a Pub’ by Ceri Richards, a powerful piece of organic abstract design by Jessica Dismorr, a fascinating if ultimately unsuccessful experimental painting by Rodrigo Moynihan, ‘Objective Abstraction’ from 1935–6, and an excellent example of John Piper’s high abstract period, from 1937. Opposite are a couple of top-flight realist canvases: William Coldstream’s portrait of Mrs Auden, mother of the poet, and a forlornly villainous self-portrait by Claude Rogers. A cluster of later work at the far end of the room keeps up the high standard: inventive sculptures by Kenneth Armitage, Lynn Chadwick, Mary and Kenneth Martin; a substantial nude by Euan Uglow; an unavoidable tabletop and kitchen interior by John Bratby at the height of his powers, heftily encrusted with paint and very much a 1950s reworking of Sickert’s great painting ‘Ennui’; and Leon Kossoff’s moving and insistently worked charcoal portrait of the writer N.M. Seedo.

The Ben Uri Gallery & Museum, currently housed in modest premises in St John’s Wood, punches triumphantly above its weight. This is a show that many a larger and better-known public institution would be proud to have put on. Its co-curators, Sarah MacDougall and Rachel Dickson, must be given much credit for their initiative and hard work. There is a sumptuous hardback catalogue (£30), well illustrated and full of useful information, a must for all enthusiasts of the period. The exhibition, which opened last year, runs for less than a month more: I urge you to visit it.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in