The current exhibition in the Sainsbury Wing claims to be a portrait of Vienna in 1900, but in fact offers rather an interesting survey of portraits made there from the 1830s to 1918. The gallery layout has been usefully adapted to display the work thematically rather than chronologically, which is more dynamic but stylistically confusing. The only way to enjoy the show is to wander at will and pick out the paintings that appeal. There are some horrors here (I wouldn’t linger over Broncia Koller), but plenty of good things as well.

The first room gives you a taste of what’s on offer: there’s a mad portrait of Emperor Franz I looking like Andy Warhol without the wig; the death mask of Beethoven and a painting of his hands; and ‘Antonie von Amerling on her Deathbed’ by her husband Friedrich. The exhibition hots up in the second room, with a marvellously disquieting double portrait by Oskar Kokoschka, of Hans Tietze and Erica Tietze-Conrat. Kokoschka is out of fashion at the moment, but he was an extraordinary painter who pushed the investigation of portraiture beyond (for many of his sitters) acceptable limits. When they complained that he had cruelly vilified them he responded airily that they would grow to resemble their portraits: apparently some of them did. His own madness and manias may have given him insight into the darker side of others. Certainly the eight paintings by him here make one eager for a full-scale Kokoschka retrospective.

His work is so much more interesting than the self-indulgent adolescent angst of Egon Schiele, however talented. I enjoyed Arnold Schönberg’s robust paintings but the real revelation for me was Richard Gerstl: tormented, radical, extremist, he revealed something of the Viennese psyche, probably before it was ready for it. His nude self-portrait done at the height of his affair with Schönberg’s wife is still shocking: self-disgust or the naked truth? Quite a contrast to turn to Gustav Klimt, the master of decoration: just look at the way the eyes, lips and jewels are accentuated in the subtle receding tide of subdued froth that is Hermine Gallia’s gown. There are lots of self-portraits, many confrontations with death (the best Schiele is a drawing of his dying pregnant wife made three days before he himself died), and a final look at Kokoschka in the last room. Let’s have that retrospective.

Francis Bacon: Second Version of Triptych 1944, 1988 © The Estate of Francis Bacon. All rights resevered. Lent by Tate, London

Francis Bacon: Second Version of Triptych 1944, 1988 © The Estate of Francis Bacon. All rights resevered. Lent by Tate, London

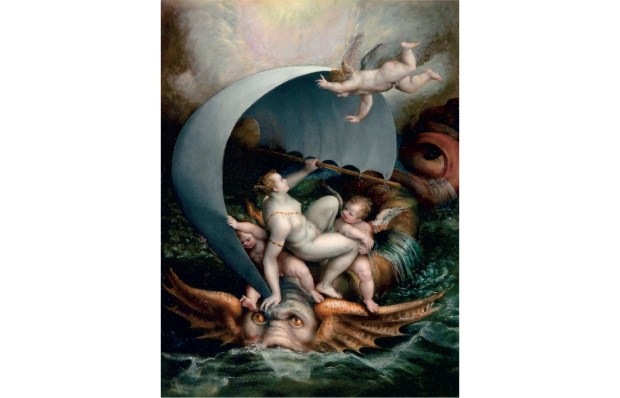

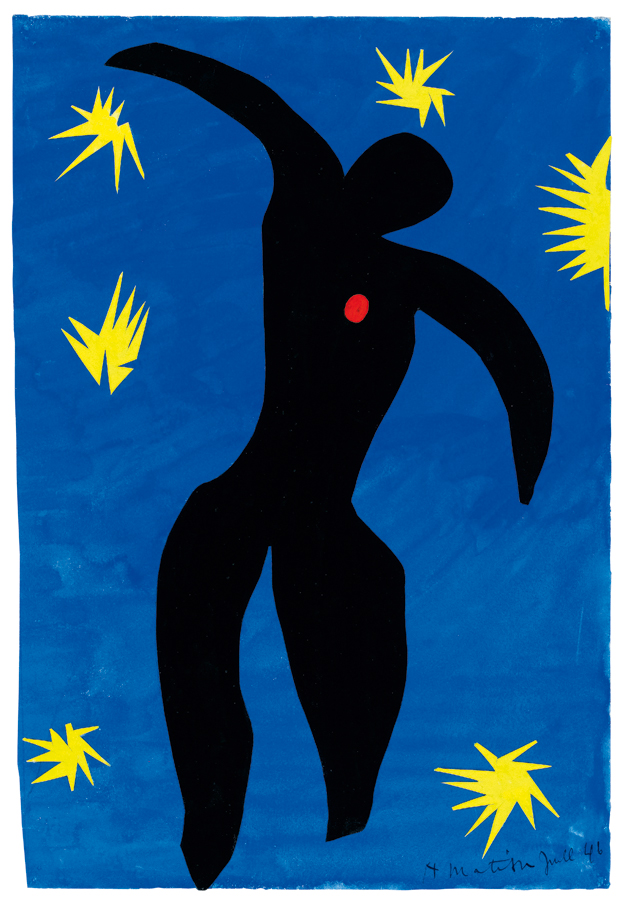

Intimate comparative shows are all the rage at the moment. Back in the summer there was Moore and Rodin at the Henry Moore Foundation in Much Hadham, and until 1 December there is Auerbach and Rembrandt at Ordovas in Savile Row — both exhibitions have been reviewed in this column. There is also Bacon and Moore at the Ashmolean, so what is the purpose of these carefully staged comparisons? Presumably to throw new light on a pair of artists by close juxtaposition of relevant works. That is not as easy as it sounds, particularly when dealing with a painter and a sculptor. The selection has to make individual sense of both artists as well as bringing something new to the equation. But if the selection is done with flair and sensitivity, the results can be most illuminating.

With Bacon and Moore, it is not so much a question of putting the work in a new context as re-establishing an old one — that of the shared mixed exhibitions of their early years. The standing of each has waxed and waned with the dictates of fashion, and if the global reputation of Moore is not quite as high as it once was (particularly in this country), the fortunes of Bacon have risen imperturbably since his death in 1992. So perhaps this exhibition does more for Moore than Bacon, though I think it serves both well by the generally high quality of exhibits brought into effective relation.

Henry Moore: Four Figures in a Setting, 1948 © The Henry Moore Foundation

Henry Moore: Four Figures in a Setting, 1948 © The Henry Moore Foundation

In the exhibition’s title, flesh obviously stands for Bacon and bone for Moore, but these distinctions are by no means absolute in the multivalent realities of their work. Bacon is not all exterior bruising and adipose tissue, Moore is not simply underlying structure. Look, for instance, at Bacon’s ‘Studio Interior’ (1936), a little-known work from a private collection, featuring a wildly biomorphic foreground figure and a sculpture looming at rear. Or consider ‘Composition’ from 1933, another unknown work, also very much involved with structure and the influence of Picasso. Moore, on the other hand, deals directly with flesh in his shelter drawings and studies of miners, or in his early nude drawings. Compare also his mixed-media study ‘Square Reclining Forms’ (1961–2), perhaps the most Baconic of his images here. This exhibition encourages us to question preconceptions and look afresh at both artists — an instructive and highly enjoyable experience.

Two more shows that deserve mention: in the spacious premises of Philip Mould & Co. (29 Dover Street, W1, until 7 December) is a remarkable museum-quality exhibition devoted to the portrait miniatures of Samuel Cooper (1607/8 to 1672). The show is entitled Warts and All as Oliver Cromwell features large in the display: four miniatures (including a rare and recently rediscovered profile portrait), together with one of his wife, Elizabeth Bourchier, Sir Peter Lely’s oil on canvas portrait (the sitting for which elicited Cromwell’s famous remark), and a 19th-century plaster cast of Cromwell’s death mask. But there are many other splendours in the show, from the Restoration for instance, namely the exquisite chalk drawing of Thomas Alcock. Samuel Cooper is billed as the greatest miniaturist of all time, and this show offers viewers a unique opportunity to make up their own minds as to his quality and achievement.

A very different kind of talent — for landscape rather than portraiture — is to be found in Ivon Hitchens: Romantic Modernist at Richard Green (33 New Bond Street, W1, until 12 December). The show is full of flaunting gestures expertly controlled, sumptuous colour and the kind of abstract painterly notation for landscape structures that has to be seen in the flesh to be fully appreciated. To my eye, the best painting is ‘Land and Sky Spaces No. 2’, in which Hitchens balances his punches superbly while making reference to such admired younger contemporaries as Roger Hilton: exhilarating.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in