Best line of the week came on Monday from the composer John Tavener, and was given added poignancy by the announcement the following day that Tavener had died. He told us, ‘Life is a creeping tragedy; that’s why I must be cheerful.’ It’s a sankalpa, or inner resolution, he held on to especially in his last years as he endured an illness that stopped his heart four times and once kept him in intensive care for six months. For a while the experience of near-death shut down his creativity completely. He had, he told us, ‘no sense of that other life which until then had enriched him’.

Tavener was talking on Start the Week, which on Monday welcomed back Andrew Marr after his remarkable recovery from catastrophic illness. Marr chose as his theme for this first programme the poems of George Herbert and the way that Herbert abandoned the life of status and ambition and devoted himself instead to making sense of his religious faith and of his inner life, his soul.

If you’re over a certain age, you’ll know Herbert’s work through lines like ‘Teach me, my God and King’ or ‘Let all the world in every corner sing’ taken from the English hymnal and once sung in school assemblies the land over. Those who are young enough to have missed out on this kind of linguistic education should look him up on Google. As Marr vividly encapsulated, Herbert’s way with words is like Shakespeare but rinsed and rinsed thoroughly until only a few pebbles remain.

Marr himself claims not to be a man of faith but since his illness he has found in Herbert’s poetry a solace, a calming of the restless mind. Herbert was writing almost 400 years ago but we can find in him surprising connections because he was writing not about the external world within which he lived, but rather about those inner quandaries and doubts that still pester and plague us. How do we have a life that is truly real while living in a world that pays no attention, or respect, to the questions asked by the soul, the inner me?

Marr was joined by the writer Jeanette Winterson and Herbert’s biographer, John Drury (who like Herbert is described, rather wonderfully, as ‘an Anglican divine’), in a conversation whose rigour and purpose quite dispelled that Monday-morning feeling. Winterson can always be relied on to say in five words what it takes most people to explain in 50. ‘The odd thing about life,’ she said, ‘is that it’s so short. The only way to lengthen it is to live for what you love…and never to give way to indifference.’ Her words were given added frisson because we knew that Marr and Tavener were sitting just inches away from her in the studio, both of them having confronted so potently the reality of life’s brevity.

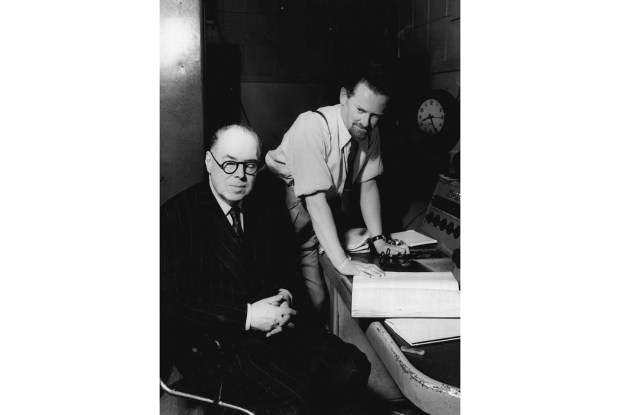

What turns Radio 4’s All in the Mind from an ‘experience’ programme into something much more interesting is the way it talks not just about mental health ‘problems’ but also engages with new research in psychology and neuroscience. It really lives up to its title — everything you need to know about what goes on inside the mind. Since it began 25 years ago, with the psychiatrist Anthony Clare in the presenter’s chair, the series has been on a mission to make us as acquainted with the mysteries of the brain as we are with the workings of the bowels. In these anniversary programmes Clare’s successor as presenter, Claudia Hammond, is trying to find out how far this has been accomplished.

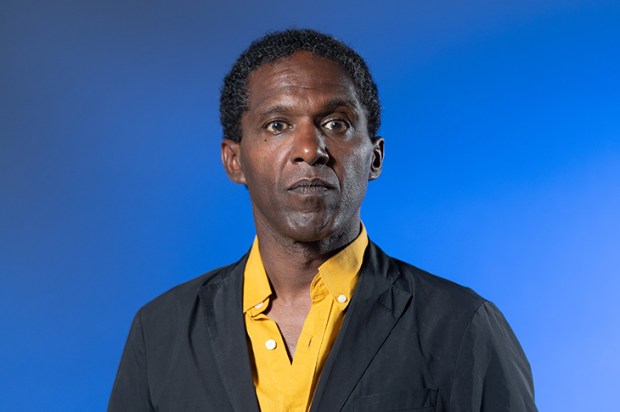

On Tuesday night she wondered how much our attitudes to mental illness have really changed since 1988. Stephen Fry, Alastair Campbell and co. are now coming out in their droves as depressives, OCDs, bipolars but does this have any impact on those sufferers from mental illness who have no celebrity profile? How different is it for them? Is it easier now to be employed after a diagnosis of mental illness? How much empathy is out there for sufferers and their families? Hammond called on Graham Thornicroft, a community psychiatrist, Paul Farmer, the chief executive of the mental-health charity Mind, and Bobby Baker, a performance artist and former patient, to give us their views. This is the strength of the series, bringing together experts and patients, looking for answers both in theory and in practice.

Back in 1988 there were still ‘asylums’ filled with long-term patients, shut away from society and forgotten. Mental illness was feared and regarded as something separate from normal society, even though at least one in ten people are likely to suffer from some kind of mental-health issue at some point in their lives. All in the Mind has played a part in ensuring we understand more about what it’s like to suffer from breakdown, anxiety, obsession, paranoia. That’s why we do still need the licence fee. To ensure that uncomfortable subjects are brought out into the open — and not simply as a freak show.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in